Desert environments represent some of the harshest conditions on Earth, with scorching daytime temperatures, freezing nights, minimal water sources, and sparse vegetation. Despite these challenges, certain lizard species have not only adapted to survive in these unforgiving landscapes but have also evolved to thrive in them.

These remarkable reptiles showcase nature’s ingenuity through specialized adaptations for water conservation, temperature regulation, and predator avoidance. From the iconic frilled lizard to the peculiar thorny devil, desert-dwelling lizards demonstrate the incredible diversity of evolutionary solutions to extreme environmental pressures.

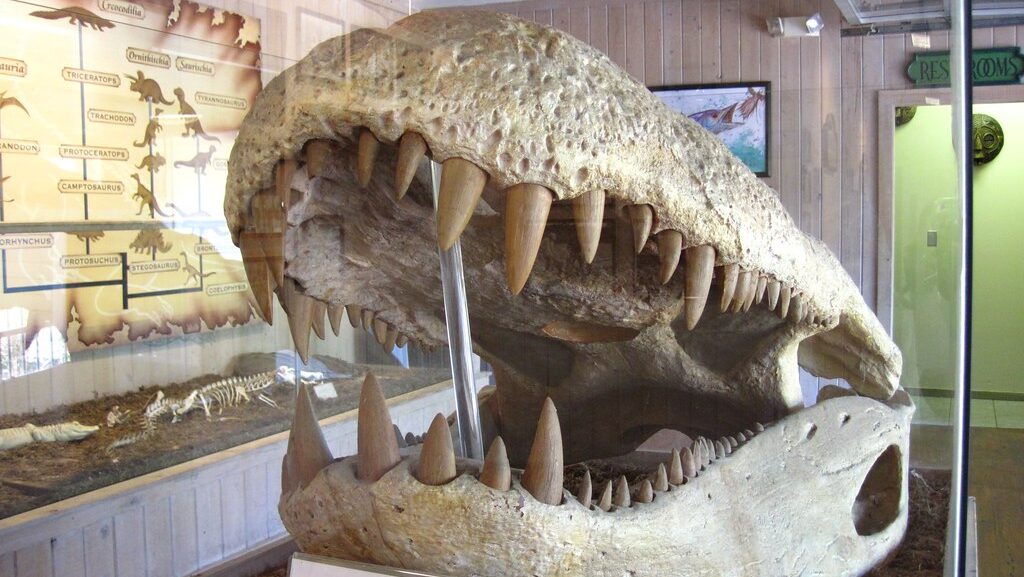

The Remarkable Gila Monster

The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) stands out as one of only two venomous lizard species in the world, making its home in the Sonoran, Mojave, and Chihuahuan deserts of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. Unlike most desert lizards that are slender and agile, the Gila monster sports a robust, heavy body that can reach up to two feet in length, adorned with striking black and orange-pink beaded scales that serve as a warning to potential predators.

These unusual reptiles can store fat in their tails and large bodies, allowing them to go months between meals—a crucial adaptation for desert environments where food sources are unpredictable. Perhaps most remarkably, Gila monsters spend up to 95% of their time underground or in burrows, emerging primarily during the breeding season and after desert rains when their prey of small mammals, birds, and eggs becomes more accessible.

The Adaptable Desert Iguana

The desert iguana (Dipsosaurus dorsalis) has mastered the art of surviving in some of North America’s hottest environments, thriving in temperatures that would prove fatal to most reptiles. These pale gray to cream-colored lizards, reaching about 16 inches in total length, possess the remarkable ability to function at body temperatures exceeding 115°F (46°C)—among the highest of any lizard species. When desert temperatures soar to extremes, these iguanas employ a fascinating behavior called “stilting,” where they lift their bodies off the scorching sand and minimize contact by extending their limbs, reducing heat absorption from the ground.

Desert iguanas are primarily herbivorous, feeding on annual wildflowers, perennial shrub leaves, and buds, with a particular fondness for the flowers and leaves of the creosote bush that dominates much of their habitat. Their specialized digestive systems allow them to extract maximum nutrition and moisture from plant matter, eliminating the need for frequent trips to water sources in their parched habitat.

The Iconic Frilled Lizard

The frilled lizard (Chlamydosaurus kingii) has become one of the most recognizable reptiles from Australia’s arid regions due to its spectacular defensive display featuring a large expandable frill around its neck. When threatened, this lizard unfurls its colorful frill, opens its bright yellow mouth, hisses loudly, and rises onto its hind legs to appear larger and more intimidating to potential predators. Primarily residing in the hot, dry woodland and scrub environments across northern Australia, these lizards spend most of their time in trees, descending to the ground only to feed or move between arboreal habitats.

The frilled lizard’s diet consists mainly of insects, spiders, and small vertebrates, which it actively hunts during the day when its reflexes are sharpened by the warmth of the sun. Their semi-arboreal lifestyle represents a unique adaptation to desert living, allowing them to escape the extreme ground temperatures while accessing different food sources than ground-dwelling lizards.

The Desert-Specialized Thorny Devil

The thorny devil (Moloch horridus) exemplifies extreme desert adaptation with its bizarre appearance and remarkable survival strategies in Australia’s harshest arid regions. Covered entirely in sharp, conical spines that deter predators, this small lizard (reaching only about 8 inches) possesses another extraordinary adaptation: microscopic channels between its scales that function like a network of tiny straws. These channels allow the thorny devil to collect water from any part of its body through capillary action, directing morning dew, rain, or even sand moisture to its mouth—essentially drinking through its skin.

Their diet consists almost exclusively of ants, with a single thorny devil capable of consuming thousands of these insects daily using its specialized sticky tongue. Moving with a distinctive, jerky gait that helps them remain camouflaged among the desert vegetation, thorny devils also possess a false “head” on the back of their neck, which they present to predators while tucking their real head protectively between their legs.

The Heat-Defying Desert Horned Lizard

The desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos), often called the “horny toad” despite being a true lizard, has developed fascinating adaptations to survive in the arid regions of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Their flattened, round bodies covered in spiny scales provide effective camouflage against the desert floor, while the prominent horns on their heads offer protection from predators. When conventional defenses fail, these lizards employ one of the animal kingdom’s most unusual defensive mechanisms: squirting blood from specialized blood vessels around their eyes, which can project the foul-tasting liquid up to four feet to confuse and repel predators like coyotes and domestic dogs.

Desert horned lizards have specialized digestive systems that allow them to process harvester ants—their primary food source—despite the ants’ strong formic acid defenses that would prove toxic to many other predators. To regulate their temperature in extreme desert conditions, these lizards practice “thermal shuttling,” moving between sun and shade throughout the day, and can also adjust their body position to minimize or maximize sun exposure as needed.

The Resilient Chuckwalla

The chuckwalla (Sauromalus ater) represents one of the largest lizard species in North America, with males reaching up to 16 inches in length and displaying impressive territorial coloration during breeding season. These herbivorous reptiles inhabit the rocky outcroppings and lava flows of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, where they have perfected a unique defensive strategy: when threatened, chuckwallas quickly retreat into narrow rock crevices, inhale air to inflate their bodies, and wedge themselves so tightly that predators cannot extract them.

Chuckwallas have evolved remarkable water conservation mechanisms, obtaining nearly all their moisture from the plants they consume, primarily flowers, buds, and leaves of desert plants like creosote bushes and brittle bush. Their dark, mottled coloration not only provides camouflage against the desert rocks but also helps them absorb heat rapidly in the morning, allowing them to reach optimal body temperature quickly after emerging from their overnight retreats in rock crevices. During the hottest summer months when food becomes scarce, chuckwallas can enter a state of estivation (summer dormancy), reducing their metabolic rate and relying on stored fat reserves until conditions improve.

The Speedy Zebra-Tailed Lizard

The zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) has earned its reputation as one of the fastest lizards in North America, capable of sprinting at speeds up to 18 miles per hour across the open desert floor. When fleeing from predators, these agile reptiles often run on their hind legs with their distinctive black-and-white striped tail curled over their back, creating a confusing visual display that makes them harder to track. Perfectly adapted to the harsh conditions of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, zebra-tailed lizards can withstand surface temperatures exceeding 160°F (71°C) by performing a behavior called “dancing,” where they rapidly alternate lifting their feet off the scorching sand.

Their diet is remarkably varied for a desert lizard, consisting of insects, smaller lizards, flowers, leaves, and even seeds, allowing them to exploit whatever food sources become available in their resource-limited environment. These lizards are most active during the hottest parts of the day when most predators seek shelter, representing an evolutionary strategy that reduces competition and predation pressure despite the physiological challenges of extreme heat.

The Sand-Diving Sandfish Skink

The sandfish skink (Scincus scincus) has evolved perhaps the most unusual locomotion method among desert lizards, quite literally “swimming” through sand as efficiently as a fish moves through water in the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East. With a streamlined body, wedge-shaped head, and smooth, polished scales that reduce friction, these lizards can completely submerge beneath the sand’s surface within seconds when threatened or seeking cooler temperatures. Their specialized lungs can withstand the pressure and limited oxygen supply while burrowed, and they’ve developed transparent “window panes” in their lower eyelids that allow them to see while protecting their eyes from sand particles.

Sandfish skinks feed primarily on insects and other small invertebrates they encounter both on the surface and within the sand, using their acute hearing to detect prey movements through vibrations in the substrate. Their remarkable adaptation to sandy environments extends to their nasal passages, which contain specialized filters to prevent sand inhalation during their subsurface travels, and their ability to regulate body temperature by adjusting their depth within the sand column throughout the day.

Desert Lizard Temperature Regulation Strategies

Desert lizards employ diverse and sophisticated temperature regulation strategies to survive in environments where ground temperatures can exceed 170°F (77°C). Many species are “thermal conformers” rather than thermal regulators, meaning they allow their body temperature to fluctuate with environmental conditions within a preferred range, retreating underground when temperatures become too extreme. Behavioral thermoregulation represents their primary adaptation, with species like the fringe-toed lizard performing complex “thermal shuttling”—moving between sun and shade throughout the day and adjusting body posture to maximize or minimize sun exposure as needed.

Some desert lizards, particularly those in the hottest regions, become crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) during summer months, shifting to full diurnal activity only during milder seasons. Physiologically, many desert lizards have evolved higher heat tolerance thresholds than their temperate cousins, with species like the desert iguana functioning optimally at body temperatures that would prove fatal to most other reptiles, allowing them to remain active and exploit food resources when competitors and predators must seek shelter.

Water Conservation Mechanisms in Desert Lizards

Desert lizards have evolved remarkable physiological and behavioral adaptations to conserve water in environments where rainfall may be sparse or absent for months or even years. Unlike mammals, most lizards produce uric acid rather than urea as their nitrogenous waste product, which can be excreted as a semi-solid paste with minimal water loss—a crucial adaptation for desert survival. Many species possess specialized scales and skin structures that reduce water loss through evaporation, while others have evolved enhanced abilities to reabsorb water in their cloaca before waste elimination.

Some desert lizards, like the thorny devil, can harvest water from morning dew or even humidity in the air through specialized micro-channels between their scales that transport moisture to their mouth through capillary action. Behaviorally, desert lizards minimize water loss by remaining in burrows during the hottest parts of the day, emerging primarily during cooler periods when evaporative water loss through respiration is reduced. Perhaps most impressively, many desert lizards obtain nearly all their water requirements from the food they consume, extracting moisture even from seemingly dry insect prey or plant matter, eliminating the need to find free-standing water sources in their arid habitats.

Predator Avoidance Adaptations

Desert environments offer limited hiding places, forcing lizards to evolve specialized predator avoidance strategies beyond simple concealment. Camouflage represents the first line of defense, with most desert lizards displaying coloration and patterns that blend seamlessly with their surroundings, from the sand-colored hues of dune-dwelling species to the mottled patterns of those inhabiting rocky terrain.

Many species have developed specialized escape behaviors, like the zebra-tailed lizard’s bipedal running or the fringe-toed lizard’s ability to “dive” beneath loose sand in seconds. Some desert lizards employ dramatic defensive displays when cornered, such as the frilled lizard’s impressive neck frill expansion or the gila monster’s open-mouthed hissing posture that showcases its venomous capabilities.

The thorny devil’s spiny body and false head, the horned lizard’s blood-squirting defense, and the chuckwalla’s rock-crevice inflation technique all represent unique evolutionary solutions to predation pressure in desert environments. Perhaps most interesting is the prevalence of tail autotomy (voluntary tail shedding) among many desert lizard species, which serves as a last-resort escape mechanism, allowing the lizard to sacrifice its tail—which continues to wiggle and distract the predator—while the lizard itself escapes to safety.

Conservation Challenges for Desert Lizards

Desert lizards face mounting conservation challenges as their specialized adaptations leave them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. Habitat destruction represents the most immediate threat, with desert development for agriculture, solar energy installations, urban expansion, and recreational activities fragmenting previously continuous lizard populations. Climate change poses perhaps the most significant long-term threat, as many desert lizards already live near their physiological limits for heat tolerance; even small temperature increases could push midday temperatures beyond survivable thresholds or alter the timing of insect emergence that many species depend upon for food.

Invasive species introduction, particularly non-native grasses that increase wildfire frequency and intensity, has dramatically altered the structure of many desert ecosystems, eliminating the open spaces many lizard species require for foraging and predator detection. Off-road vehicle use in desert environments directly impacts lizard populations through crushing individuals and collapsing burrow systems, while also contributing to soil compaction and destruction of vegetative cover that provides essential microhabitats. Conservation efforts face the additional challenge that many desert lizard species remain poorly studied, with basic information about population sizes, distribution ranges, and specific habitat requirements still lacking for effective protection and management planning.

Conclusion

The eight lizard species highlighted in this article demonstrate the remarkable diversity of adaptations that allow reptiles to thrive in Earth’s most challenging environments. From the Gila monster’s venom and fat storage to the thorny devil’s water-harvesting skin, these specialized creatures showcase nature’s ingenious solutions to the problems of extreme heat, water scarcity, and predation pressure.

As climate change continues to intensify desert conditions worldwide, these highly adapted species may provide valuable insights into biological resilience under environmental stress. However, their specialized nature also makes them particularly vulnerable to habitat disturbance and climate shifts beyond their adaptive capacity. Protecting these remarkable desert specialists requires both targeted conservation efforts and broader commitments to preserving intact desert ecosystems as living laboratories of evolutionary adaptation.

Leave a Reply