In the vast panorama of Earth’s creatures, few animals embody longevity quite like turtles. These ancient reptiles have perfected the art of slow living, with some individuals surpassing the lifespans of nations and empires. While humans celebrate reaching their centennial, certain turtles might consider such a milestone merely middle age. Their remarkable ability to endure through decades—and in some cases, centuries—offers fascinating insights into aging, adaptation, and survival. From giant tortoises roaming remote islands to beloved pets outliving multiple generations of owners, these shelled Methuselahs challenge our understanding of biological timekeeping. This exploration into the world’s oldest turtles reveals not just record-breaking ages, but the extraordinary stories and scientific mysteries behind their extended journeys through time.

Tu’i Malila: The Gift to Royalty That Lived 188 Years

Among the most well-documented long-lived tortoises was Tu’i Malila, a radiated tortoise that lived to the remarkable age of 188 years. Captain James Cook presented this tortoise as a gift to the royal family of Tonga in 1777, where it remained until its death in 1965. Throughout its long life, Tu’i Malila witnessed the reign of numerous Tongan monarchs and became a beloved national symbol. The tortoise survived through periods of significant historical change, from the age of sail through two world wars and into the atomic era. Its exceptional longevity was attributed to the consistent care it received in the royal household, a natural diet, and the favorable climate of the South Pacific islands that closely resembled its native Madagascar habitat.

Jonathan: The Current Record Holder Still Going Strong

Currently recognized as the oldest known living land animal, Jonathan is a Seychelles giant tortoise estimated to be about 191 years old as of 2023. Residing on the island of Saint Helena, Jonathan was already fully mature when he arrived in 1882, suggesting a birth year around 1832 during the Georgian era. Despite his advanced age, Jonathan maintains an active lifestyle, though he has lost his sense of smell and is now blind from cataracts. His caretakers at Plantation House, the governor’s residence, have adapted his diet to maintain his health, including providing higher-calorie foods to compensate for his decreasing efficiency in extracting nutrients. Jonathan has become so iconic that he appears on the Saint Helena five-pence coin and continues to fascinate scientists studying the biological mechanisms behind such exceptional longevity.

Adwaita: The 255-Year-Old Wonder of Calcutta

Perhaps the most extraordinary turtle longevity case was Adwaita, an Aldabra giant tortoise believed to have lived approximately 255 years. According to historical records, Adwaita was among four tortoises brought to India by British sailors in the 18th century, eventually becoming the property of Robert Clive of the British East India Company before being transferred to Alipore Zoological Gardens in Calcutta in 1875. Carbon dating of his shell after his death in 2006 supported the estimate of his exceptional age, suggesting he was born around 1750. During his lifetime, Adwaita witnessed the rise and fall of the British Empire in India, the country’s independence, and its emergence as the world’s largest democracy. His diet consisted primarily of wheat bran, carrots, lettuce, soaked gram, bread, grass, and salt, all delivered on a strict schedule that may have contributed to his remarkable lifespan.

Harriet: Darwin’s Companion Who Survived 175 Years

Harriet the Galápagos tortoise lived approximately 175 years, with a story connecting her to one of history’s most influential scientists. According to accounts, Harriet was collected by Charles Darwin himself during his famous voyage on the HMS Beagle in 1835, though some historians dispute this direct connection. After spending time in Britain, she was transported to Australia, where she lived at several locations before settling at Australia Zoo under the care of Steve Irwin and his family. Harriet became a beloved attraction and ambassador for conservation until her death in 2006. Her remarkable journey from the Galápagos Islands to becoming one of the oldest known animals in captivity illustrates both the adaptability of these creatures and their incredible biological resilience across changing environments and care conditions.

The Biology Behind Turtle Longevity

The exceptional lifespan of turtles and tortoises stems from several biological adaptations that have evolved over millions of years. Their slow metabolic rates mean they process energy more efficiently and accumulate cellular damage more slowly than mammals with faster metabolisms. Unlike most vertebrates, many turtle species show negligible senescence, meaning they don’t experience the typical age-related decline in reproductive capacity or increased mortality rates with age. Their cells contain powerful antioxidant compounds that help prevent damage from free radicals, while their immune systems remain robust throughout their lives. Perhaps most remarkably, turtle telomeres (the protective caps at the end of chromosomes that typically shorten with age in other animals) appear to maintain their length better, potentially explaining why turtles don’t seem to have the same cellular “aging clock” as most other vertebrates.

Slow Growth and Late Maturity: The Tortoise Life Strategy

The extraordinary longevity of giant tortoises is directly connected to their slow growth rates and delayed sexual maturity. Unlike mammals that develop quickly and reproduce early, tortoises like the Galápagos and Aldabra species may take 20-30 years to reach sexual maturity. This extended development period allows their bodies to build stronger foundational systems and more robust cellular repair mechanisms. Their slow pace of life extends to virtually all biological processes—from digestion and heart rate to cellular replication and repair. The “live slow, die old” strategy has proven remarkably successful, allowing these species to survive for millions of years with relatively few evolutionary changes. This life history pattern represents an alternative evolutionary strategy where quality and durability of the organism is prioritized over rapid reproduction and population growth.

Diet and Caloric Restriction in Long-Lived Turtles

The dietary habits of the world’s oldest turtles reveal important insights into their longevity secrets. Most record-breaking tortoises consumed primarily plant-based diets rich in fibrous vegetation, which naturally restricted their caloric intake while providing essential nutrients. This natural form of caloric restriction without malnutrition activates numerous cellular pathways associated with longevity, including sirtuins and FOXO proteins that regulate aging processes. The Galápagos tortoise typically eats cacti, grasses, leaves, and fruit—foods that are high in micronutrients but relatively low in protein and fat. Additionally, many long-lived tortoises experienced periods of food scarcity in their natural habitats, creating cycles of mild fasting that may have triggered cellular autophagy—a process where cells recycle damaged components and potentially extend lifespan. The consistent, measured feeding schedules maintained for turtles in captivity might inadvertently replicate some of these beneficial dietary patterns.

Environmental Factors Contributing to Extended Lifespans

The environments where record-breaking turtles have thrived share several characteristics that likely contribute to their longevity. Most notably, giant tortoises evolved on remote islands with few predators, allowing them to develop their slow-moving lifestyle without excessive mortality risks. The relatively stable tropical or subtropical climates of places like the Galápagos, Seychelles, and Aldabra provide year-round access to vegetation without the physiological stress of extreme temperature fluctuations. For captive long-lived specimens, consistent temperature and humidity control has eliminated the environmental stressors that might otherwise accelerate aging processes. Low exposure to environmental toxins and pollutants in their natural habitats or carefully managed captive settings has also minimized cellular damage from external sources. The combination of these environmental factors creates ideal conditions for their cellular preservation systems to function optimally throughout their extended lives.

The Role of Shell Protection in Extending Life

The turtle’s iconic shell represents more than just physical protection—it’s a critical component of their longevity equation. By providing nearly impenetrable defense against most predators, the shell dramatically reduces mortality risk throughout the turtle’s life, allowing more individuals to reach advanced ages. The carapace and plastron (top and bottom shell sections) contain vital organs in a protective bony chamber that shields them from physical trauma that would be fatal to most other animals. Beyond protection from predation, the shell also provides crucial thermal regulation, helping turtles maintain optimal body temperatures without expending excessive metabolic energy. For the oldest recorded specimens, their well-maintained shells have served as lifetime shelters, with some showing remarkable self-repair abilities even after significant damage. This architectural marvel of evolution has allowed turtles to outlast countless other species that evolved alongside them millions of years ago.

Genetics and DNA Repair in Century-Old Turtles

Recent scientific studies examining the genetics of long-lived turtles have revealed fascinating adaptations at the molecular level that contribute to their exceptional lifespans. Giant tortoise genomes show expanded families of genes associated with DNA repair, immune function, and cancer suppression compared to shorter-lived vertebrates. Researchers have identified specific genes like NAD kinase, which helps regulate metabolism and cellular energy, that show enhanced expression in these ancient reptiles. The efficiency of their DNA repair mechanisms appears particularly remarkable, with cells capable of correcting mutations and damage that would lead to cancer or cellular senescence in mammals. Scientists examining cells from centenarian tortoises have observed that they maintain youthful gene expression patterns even in advanced age, suggesting their cellular machinery resists the typical age-related deterioration seen in most animals. These genetic adaptations represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement that has optimized their bodies for the long haul.

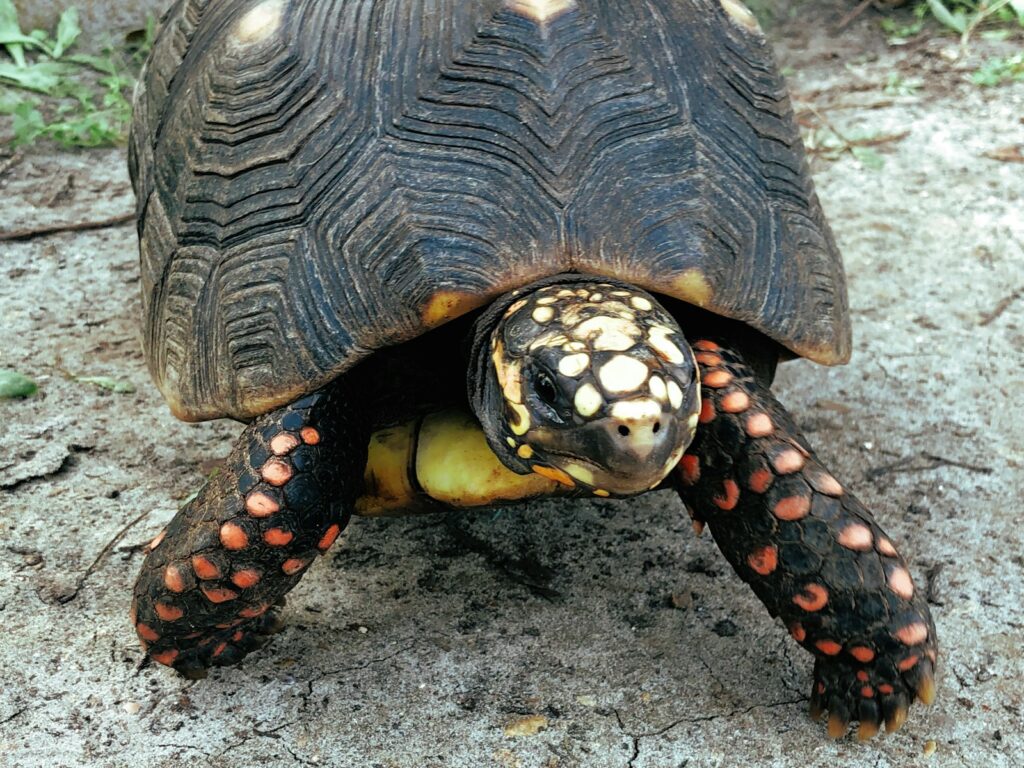

Record-Breaking Freshwater Turtles

While giant tortoises dominate longevity records, several freshwater turtle species have also demonstrated remarkable lifespans that far exceed human expectations. The eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina) has documented cases exceeding 100 years in both wild and captive settings, with one specimen found in the wild estimated to be 138 years old based on shell growth rings and historical markings. Common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) regularly live beyond 80 years, with some individuals in northern latitudes estimated to reach 170 years. The documented case of a female common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) living to 107 years in captivity demonstrates that even medium-sized freshwater species can achieve extraordinary lifespans under proper conditions. Unlike their tortoise cousins, these freshwater species maintain more active lifestyles while still achieving century-spanning lives, suggesting multiple evolutionary pathways to exceptional longevity within the turtle lineage.

Human Caretaking: Helping Turtles Reach Record Ages

The relationship between humans and record-breaking turtles reveals important insights about how proper care can maximize their natural longevity potential. For specimens like Jonathan and formerly Harriet, consistent veterinary monitoring has addressed health issues that might have been fatal in the wild, including shell infections, nutritional deficiencies, and age-related conditions. Caretakers have learned to provide specialized diets that balance nutritional needs with the beneficial aspects of caloric restriction, often adjusting feeding regimens as the animals age. Protection from temperature extremes, predators, and human interference has eliminated many common mortality factors. Perhaps most importantly, the multi-generational commitment to these animals—with care protocols passed down through successive human caretakers—has provided the consistent environment these slow-living creatures need to reach their biological potential. The stories of these record-holders demonstrate that with proper stewardship, turtles can outlive not just their caretakers but sometimes entire human institutions.

Lessons from Turtle Longevity for Human Aging Research

The extraordinary lifespans of turtles have made them valuable subjects for comparative biology and aging research, offering potential insights for human longevity science. Researchers studying negligible senescence in turtles have identified cellular mechanisms that might someday be replicated in human medicine to slow age-related decline. The efficient DNA repair systems of long-lived turtles are being examined for applications in cancer prevention, as understanding how their cells resist malignant transformation could lead to new therapeutic approaches. Their remarkable resistance to organ system deterioration, particularly cardiovascular health, provides models for maintaining functional systems throughout extended lifespans. Some scientists even propose that the slow, deliberate pace of turtle life—from metabolism to reproduction—offers philosophical as well as biological wisdom about sustainable living that might benefit human health. As research continues, these ancient creatures may help unlock biological secrets that could extend not just human lifespan but also health span—the period of life spent in good health.

Conservation Implications of Long-Lived Turtle Species

The extreme longevity of turtles creates unique conservation challenges and opportunities for protecting these remarkable species. Many giant tortoise species with the greatest longevity potential are critically endangered, with populations decimated by historical exploitation and habitat loss. Their slow reproductive rates—a natural consequence of their long-lived strategy—means populations recover extremely slowly from decline, making each breeding individual extraordinarily valuable to species survival. Conservation programs focused on these species must plan on multi-generational timescales, with recovery efforts potentially spanning centuries rather than decades. Paradoxically, their longevity also offers hope, as even small remnant populations can persist for extended periods if properly protected, giving conservation efforts time to succeed. The stories of the oldest known individuals serve as powerful conservation ambassadors, helping the public connect with species that have witnessed history across multiple human generations and deserve protection for generations to come.

The extraordinary longevity of the world’s oldest turtles represents one of nature’s most remarkable achievements—a testament to evolutionary success measured not in competitive dominance but in sheer persistence through time. From Jonathan’s continuing journey through three centuries to the historical legacy of Adwaita’s 255-year life, these animals challenge our understanding of biological limits. Their secrets—slow metabolism, efficient cellular repair, protective anatomy, and measured life rhythms—offer both scientific insights and philosophical wisdom about sustainable existence. As we continue to unravel the biological mechanisms behind their extended lifespans, we gain not only potential pathways to address human aging but also a deeper appreciation for these ancient mariners who have mastered the art of navigating through time. In their patient, centuries-spanning lives, turtles remind us that sometimes the most enduring success comes not to those who race through life, but to those who proceed with steady determination, one slow step at a time.

Leave a Reply