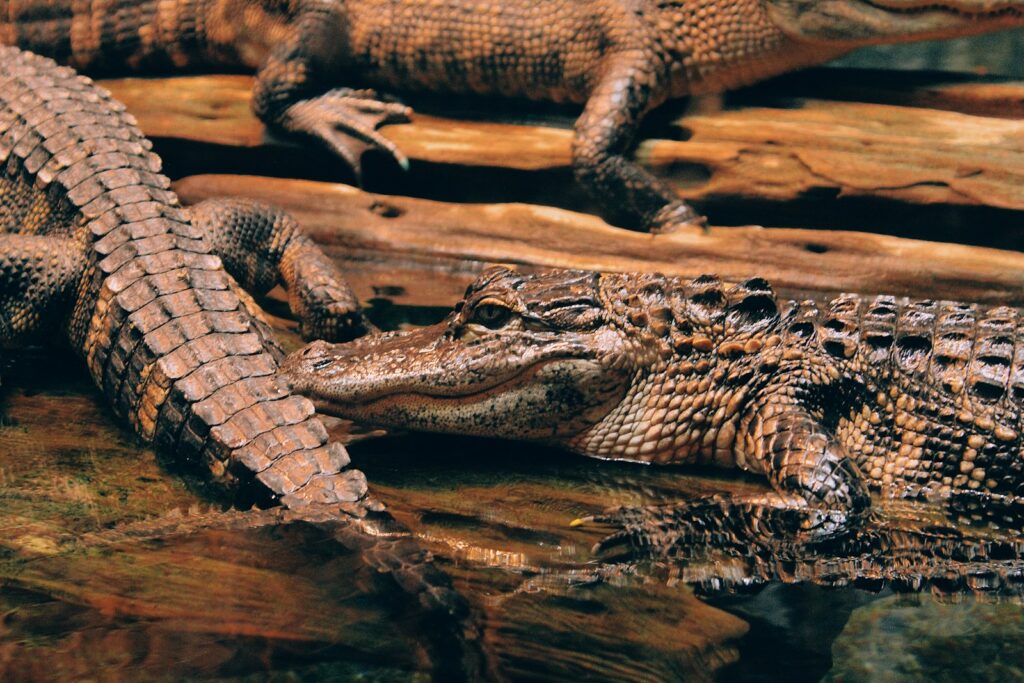

Deep in the murky waters of rivers and swamps across the tropics, an ancient predator has evolved with remarkable resilience. Crocodiles, having survived for over 200 million years, possess extraordinary physical adaptations that make them virtually impervious to many attacks, including, surprisingly, gunfire. Their legendary toughness isn’t just folklore; it’s rooted in evolutionary adaptations that have made these reptiles living tanks. From their armored skin to their remarkable healing abilities, crocodiles represent one of nature’s most impressive examples of physical durability. Their ability to withstand serious injury has fascinated scientists, hunters, and wildlife enthusiasts alike, offering insights into natural defense mechanisms that have stood the test of time.

The Evolutionary Armor: Crocodile Skin Structure

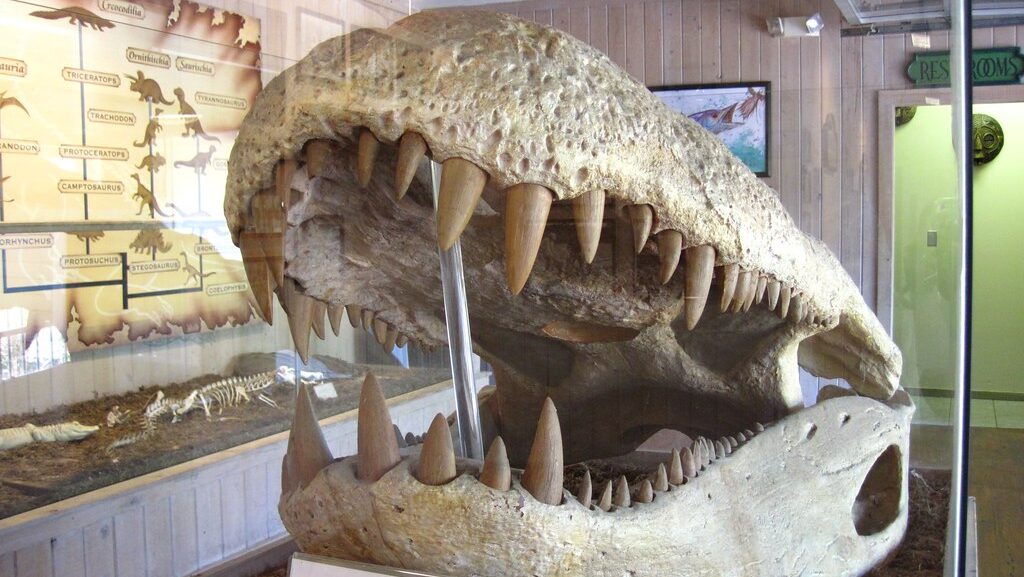

A crocodile’s first line of defense is its remarkable skin, which serves as natural body armor. Unlike the scales of most reptiles, crocodiles possess osteoderms—bony deposits that form protective plates within their leathery skin. These osteoderms create a chainmail-like structure that can deflect projectiles, including, in some cases, bullets. The osteoderms vary in thickness and distribution across the body, with the back and neck regions typically having the most substantial protection. Interestingly, the belly lacks these bony plates, which is why hunters and predators typically target this more vulnerable area. This evolutionary armor hasn’t changed significantly in millions of years, demonstrating the effectiveness of this natural defense system.

Bulletproof Myth: The Truth About Crocodile Skin and Gunfire

While crocodiles have earned a reputation for being “bulletproof,” this characterization isn’t entirely accurate. The reality is more nuanced—their skin can deflect small-caliber bullets, particularly when striking at shallow angles against the osteoderms on their backs. However, high-powered rifles and direct shots can certainly penetrate crocodile hide. Historical accounts from big game hunters often mention needing large-caliber weapons to effectively hunt crocodiles, with shots to the softer underbelly or the small brain being the only reliable methods. Many bullets that do strike the armored portions may be deflected or have their velocity significantly reduced, causing only superficial damage rather than fatal injuries. This partial resistance to gunfire is remarkable when compared to most other animals and contributes to the crocodile’s formidable reputation.

The Science of Osteoderms: Natural Body Armor

Osteoderms represent one of nature’s most effective armor systems, consisting of bony plates embedded within the dermal layer of a crocodile’s skin. Each osteoderm contains a complex network of collagen fibers that provide flexibility while maintaining strength, allowing crocodiles to move freely despite their armored exterior. Scientific analysis has revealed that these structures are composed primarily of calcium phosphate, similar to human bones, but arranged in a unique lattice pattern that maximizes impact resistance. The osteoderms interlock like puzzle pieces, creating a flexible yet durable shield that distributes force from impacts across a wider area. This natural armor system has inspired biomimetic research, with engineers studying crocodile skin to develop improved body armor for military and law enforcement applications.

Blood-Borne Immunity: Antimicrobial Properties

Crocodiles possess a remarkable immune system that contributes significantly to their ability to recover from severe injuries. Their blood contains powerful antimicrobial peptides that can kill a wide range of bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains that pose serious threats to humans. These natural antibiotics allow crocodiles to heal from deep wounds in bacteria-laden environments that would cause deadly infections in most other animals. Research has shown that crocodile blood can neutralize HIV, E. coli, and even methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Scientists studying these properties hope to develop new antibiotics based on crocodile blood peptides to combat the growing problem of antibiotic resistance in human medicine. This exceptional immune response explains how crocodiles can survive in pathogen-rich environments with open wounds that would prove fatal to most vertebrates.

Metabolic Marvels: How Crocodiles Heal

The healing abilities of crocodiles are intimately connected to their unique metabolism, which allows them to survive for extended periods without food while diverting energy to repair processes. Unlike mammals, which maintain constant body temperatures and high metabolic rates, crocodiles can lower their metabolism during healing, effectively entering a state of controlled hibernation that prioritizes recovery. This metabolic flexibility means they can survive severe injuries that would cause fatal shock in mammals. Crocodiles can also shunt blood away from injured areas, reducing blood loss and preserving vital functions while healing begins. Their tissue regeneration capabilities, while not as dramatic as some salamanders that can regrow limbs, still exceed those of most vertebrates, allowing them to recover from deep lacerations and even loss of appendages like tails. This combination of metabolic control and tissue regeneration makes them extraordinarily resilient to injury.

Battle Scars: Crocodile Fighting and Injury Recovery

Territorial disputes and mating competitions between male crocodiles often result in brutal battles that would be fatal to most animals. These confrontations frequently lead to severe injuries, including deep lacerations, broken bones, and even lost limbs or tails. Remarkably, most crocodiles survive these encounters and fully recover, often bearing numerous scars as evidence of their violent history. Wildlife researchers have documented individuals missing entire limbs that continue to thrive, adapting their hunting and movement patterns to compensate for their injuries. One famous example is “Brutus,” a large saltwater crocodile from Australia’s Adelaide River, who lost his right front leg but continued to grow to an impressive size and remains a dominant predator in his territory. The ability to recover from such catastrophic injuries demonstrates the extraordinary resilience that makes crocodiles one of nature’s ultimate survivors.

Pain Resistance: The Crocodile’s Neural Adaptations

Crocodiles exhibit a remarkable tolerance for what would be excruciating pain in mammals, allowing them to continue functioning despite serious injuries. Research suggests their nervous systems process pain differently, with specialized neural adaptations that moderate pain perception without eliminating it entirely. This doesn’t mean crocodiles don’t feel pain—they possess nociceptors (pain receptors) similar to other vertebrates—but rather that their response to pain signals differs significantly from mammals. Observations of injured crocodiles show they can continue hunting, defending territory, and engaging in normal behaviors shortly after sustaining severe wounds. This pain modulation system represents an evolutionary advantage, allowing crocodiles to remain functional in dangerous situations where pain might otherwise incapacitate them. Scientists studying these mechanisms hope to develop improved pain management strategies for human medicine by understanding how crocodiles naturally regulate their pain response.

Vascular Control: The Secret to Surviving Blood Loss

One of the most remarkable adaptations allowing crocodiles to survive serious injuries is their sophisticated cardiovascular control system. Unlike mammals, crocodiles can selectively shut down blood flow to certain body regions, effectively creating internal tourniquets that prevent blood loss from wounded areas. This vascular control is managed by specialized heart valves and muscles that can redirect blood flow as needed. When a crocodile is injured, this system allows them to maintain blood pressure and continue delivering oxygen to vital organs while minimizing hemorrhage from wounds. The crocodile heart, with its unique four-chambered structure that can function as either a three-chambered or four-chambered heart depending on circumstances, plays a crucial role in this adaptive circulatory response. This vascular control system explains how crocodiles can survive injuries that would cause fatal blood loss in most other animals.

Thermal Regulation and Healing: The Temperature Connection

Crocodiles strategically use environmental temperature to accelerate their healing process, a behavior known as “therapeutic basking.” As ectotherms (cold-blooded animals), crocodiles rely on external heat sources to regulate their body temperature, and they exploit this dependency to optimize healing conditions. Injured crocodiles typically spend more time basking in the sun, raising their body temperature to enhance immune function and accelerate tissue repair. Higher body temperatures increase metabolic rates in the affected areas, speeding up the inflammatory response and cellular regeneration. Conversely, when fighting infection becomes necessary, crocodiles may seek cooler water to induce a form of “fever” that helps combat pathogens. This temperature-dependent healing strategy represents a sophisticated behavioral adaptation that complements their physiological defenses against injury and infection.

Historical Accounts: Crocodile Resilience Through Human Eyes

Historical literature contains numerous accounts of crocodiles’ extraordinary ability to withstand gunfire and recover from seemingly fatal wounds. Big game hunters from the colonial era frequently reported needing multiple large-caliber shots to kill crocodiles, with many recounting stories of animals escaping after being shot repeatedly. In his 1923 book “The Man-Eaters of Tsavo,” Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson described shooting a crocodile multiple times, only to have it escape into the water and survive. Similar accounts appear in the journals of explorers across Africa, Australia, and Southeast Asia. Indigenous peoples who have coexisted with crocodiles for thousands of years incorporated this knowledge into their hunting techniques, developing specialized strategies that target the few vulnerable areas crocodiles possess. These historical observations, while sometimes exaggerated, consistently highlight the remarkable resilience that modern science has confirmed through more rigorous study.

Conservation Implications: Resilience in a Changing World

While crocodiles possess remarkable physical resilience, they remain vulnerable to broader environmental threats that their natural armor cannot defend against. Habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and hunting have significantly impacted crocodile populations worldwide, with several species now endangered. Ironically, the very toughness that allows individual crocodiles to survive injuries has contributed to a false perception of species invulnerability that has sometimes hindered conservation efforts. The reduction of wetland habitats represents a particular threat, as it concentrates crocodile populations in smaller areas, increasing competition and human-wildlife conflict. Conservation strategies now focus on protecting these crucial habitats and establishing sustainable management practices that acknowledge both the resilience and the vulnerability of these ancient reptiles. Understanding the remarkable adaptations that make crocodiles so tough has become an important component of efforts to ensure their long-term survival.

Biomimicry: Learning from Nature’s Design

The extraordinary defensive capabilities of crocodiles have not gone unnoticed by scientists and engineers seeking to develop improved protective technologies. Researchers in the field of biomimicry study crocodile skin structure to inspire designs for more effective body armor, with particular interest in how the interlocking osteoderms create flexibility without sacrificing protection. The antimicrobial properties of crocodile blood have sparked research into new antibiotics and wound-healing compounds that could revolutionize medical treatment. Military engineers have examined how the layered arrangement of collagen fibers in crocodile skin might inform the development of next-generation ballistic armor that remains flexible while offering enhanced protection. Even the pain modulation systems of crocodiles are being studied for insights that might lead to improved pain management strategies for human patients. These biomimetic applications demonstrate how understanding nature’s solutions to survival challenges can inspire technological innovations with broad benefits for humanity.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Survivors

Crocodiles stand as testament to the extraordinary resilience that evolution can produce when survival pressures remain consistent over millions of years. Their ability to withstand injury, including gunfire in some circumstances, represents the culmination of numerous specialized adaptations working in concert—from armored skin and powerful immune responses to sophisticated cardiovascular control and pain modulation. While not truly bulletproof in the literal sense, crocodiles possess a combination of physical and physiological defenses unmatched in the animal kingdom. Their survival through mass extinction events that claimed the dinosaurs further underscores their extraordinary adaptability. As we continue to study these remarkable reptiles, we gain not only a deeper understanding of evolutionary biology but also valuable insights that may inform medical treatments, protective technologies, and conservation strategies. In the crocodile, nature has created one of its most perfect survival machines—a living tank that continues to thrive in a world of constant change.

Leave a Reply