Deep in the Indonesian archipelago, a prehistoric-looking creature silently stalks its prey with remarkable patience. The Komodo dragon, the world’s largest living lizard, has captivated scientists and wildlife enthusiasts alike with its imposing presence and unique hunting strategies. These remarkable reptiles, with their armored scales, powerful limbs, and lethal hunting abilities, represent one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary success stories. From their isolated island habitat to their complex biology and behavior, Komodo dragons embody the fascinating diversity of the reptile world while providing crucial insights into evolution, adaptation, and conservation. Join us as we explore the extraordinary world of these magnificent creatures that seem to have stepped straight out of the age of dinosaurs.

The Ancient Origins of Komodo Dragons

Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) belong to the monitor lizard family Varanidae, with evolutionary roots tracing back millions of years. Fossil evidence suggests that these impressive reptiles descended from ancestors that originated in Asia approximately 40 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. Their journey to the Indonesian islands likely occurred during periods of lower sea levels when land bridges connected what are now isolated islands. Once sea levels rose again, these giant lizards became stranded on their island homes, evolving in isolation with limited competition from other large predators. This geographical isolation played a crucial role in their evolution into the massive proportions we see today, demonstrating a classic example of island gigantism, where species grow significantly larger than their mainland relatives due to reduced predation pressure.

Island Home: The Limited Distribution of Komodo Dragons

Komodo dragons inhabit a remarkably restricted natural range, found only on five islands in eastern Indonesia: Komodo, Rinca, Flores, Gili Motang, and Gili Dasami. These islands, part of Komodo National Park (established in 1980), provide the specific environmental conditions these specialized reptiles require to thrive. The islands feature a combination of savanna grasslands, tropical dry forests, and beach vegetation that creates the perfect habitat mosaic for these adaptable predators. Their limited distribution makes them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes and human encroachment, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts in the region. The volcanic origins of these islands have created unique topographies with rugged hills and seasonal water sources that influence the dragons’ movement patterns and behaviors throughout the year.

Physical Characteristics: Built for Dominance

The Komodo dragon’s physical presence commands immediate respect, with adult males typically reaching 8-10 feet in length and weighing up to 200 pounds, making them the heaviest lizards on Earth. Their muscular bodies are covered in rough, bead-like scales in varying shades of brown, gray, and reddish hues that provide camouflage in their natural environment. The dragon’s powerful limbs support a surprisingly agile frame, allowing these giants to run up to 13 miles per hour in short bursts when pursuing prey. Their most distinctive feature might be their disproportionately large, muscular tail, nearly equal to their body length, which serves multiple purposes including balance, swimming propulsion, and use as a defensive weapon. Female Komodo dragons tend to be somewhat smaller than males, with more pronounced size differences becoming apparent as they reach full maturity around 8-9 years of age.

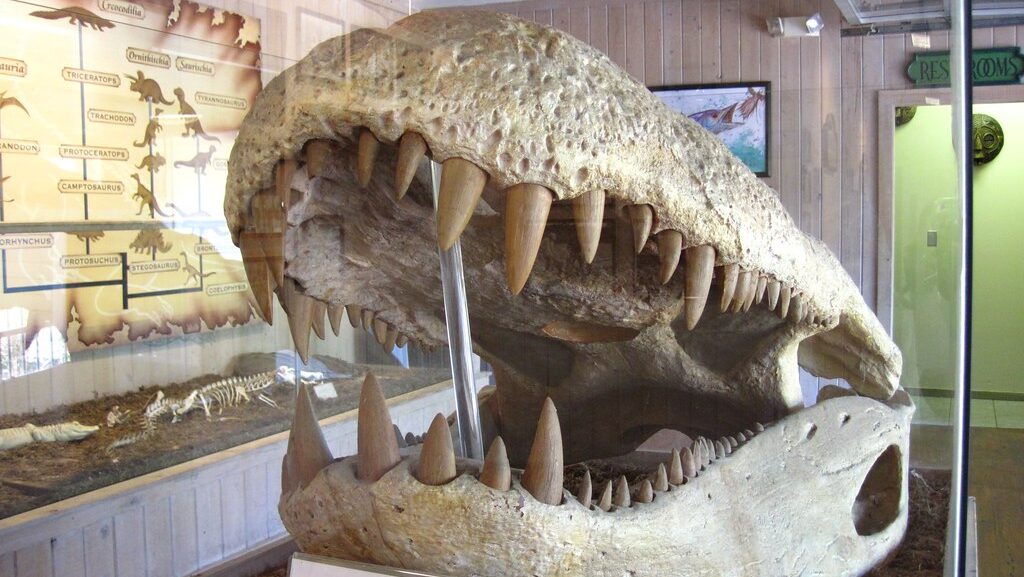

The Deadly Jaws and Teeth of the Dragon

The Komodo dragon’s mouth houses an arsenal of up to 60 serrated, replaceable teeth designed specifically for slicing through flesh and bone. Unlike most reptiles, these specialized teeth can grow up to one inch in length and curve inward, allowing the dragon to maintain a secure grip on struggling prey. Their powerful jaw muscles can deliver a bite force estimated at 1,200 pounds per square inch, more than enough to crush the bones of deer, pigs, and other prey animals that constitute their diet. When feeding, Komodo dragons can consume up to 80% of their body weight in a single meal, often swallowing large chunks of meat whole rather than thoroughly chewing their food. Remarkably, their jaw flexibility allows them to open their mouths extraordinarily wide, sometimes up to 80 degrees, enabling them to consume impressively large portions of prey at once.

Venom vs. Bacteria: The Truth About Their Deadly Bite

For decades, scientists believed that Komodo dragon bites were deadly primarily due to bacteria festering in their mouths from rotting meat particles. However, groundbreaking research in 2009 revealed that Komodo dragons actually possess venom glands in their lower jaws that produce toxins capable of preventing blood clotting, lowering blood pressure, and inducing muscle paralysis in their prey. When a Komodo dragon bites its victim, these venom compounds enter the bloodstream and begin a cascade of physiological effects that weaken the prey animal over time. This venom-delivery system explains why Komodo dragons often bite larger prey and then patiently track them for hours or even days until the animals succumb to the venom’s effects. While bacterial infection certainly plays a role in weakening bitten prey, the venom represents the primary weapon in the dragon’s hunting arsenal, reshaping our understanding of these ancient reptiles’ predatory adaptations.

Hunting Strategies: Patient Predators

Komodo dragons employ a hunting strategy that combines ambush techniques with remarkable patience and persistence. These cunning predators often position themselves along game trails or near water sources, remaining motionless for hours until unsuspecting prey comes within striking distance. When attacking, they use their powerful legs to lunge forward with surprising speed, targeting the throat, belly, or legs of their prey with their serrated teeth. For larger prey like deer or water buffalo that don’t immediately succumb to the initial attack, Komodo dragons will follow the wounded animal for miles if necessary, using their excellent sense of smell to track the blood trail. This tracking behavior can continue for days, with the dragon periodically checking on its weakening victim until it finally collapses from blood loss, shock, or venom effects. The communal nature of feeding means that once a large animal falls, the scent of blood may attract other dragons from considerable distances, leading to competitive feeding frenzies.

The Remarkable Senses of Komodo Dragons

Komodo dragons possess an extraordinary sensory system that makes them formidable hunters in their island habitats. Their most impressive sense is their ability to detect scents, using a forked tongue to collect air particles and transfer them to the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of their mouth for analysis, similar to snakes. This remarkable chemosensory system allows them to detect carrion from up to 5-6 miles away under ideal conditions, and to track wounded prey with precision for days on end. While their eyesight is relatively good and can detect movement at distances up to 300 meters, their visual acuity is best suited for spotting movement rather than distinguishing fine details. Komodo dragons also possess limited but functional hearing capabilities, primarily detecting low-frequency sounds that might indicate approaching prey or potential threats in their environment. The integration of these sensory systems creates a highly efficient predator adapted perfectly to the challenging hunting conditions of their island ecosystem.

Reproduction and the Miracle of Parthenogenesis

The reproductive biology of Komodo dragons includes one of the most fascinating adaptations in the reptile world—the ability to reproduce through parthenogenesis. This remarkable process allows female Komodo dragons to produce viable eggs without male fertilization, essentially cloning themselves when no males are available for mating. During normal sexual reproduction, males engage in competitive combat during breeding season, wrestling with their powerful forelimbs to establish dominance and earn mating privileges. After successful mating, females dig nest chambers in sandy soil where they deposit between 15-30 eggs, which they actively guard for several months before abandoning them to develop independently. The incubation period typically lasts 7-9 months, with temperature during development determining the sex of the offspring—warmer temperatures produce males while cooler conditions result in females. This temperature-dependent sex determination creates interesting population dynamics that researchers continue to study across the dragons’ limited range.

Social Behavior and Hierarchies

Contrary to early assumptions that Komodo dragons were strictly solitary, research has revealed a complex social structure among these massive reptiles. Adult dragons establish and maintain dominance hierarchies primarily based on size, with larger individuals gaining priority access to feeding sites and preferred basking locations. During competitive feeding situations, these hierarchies become clearly apparent, with dominant individuals feeding first while smaller dragons wait their turn or attempt to steal morsels without confrontation. Interestingly, research has documented that related individuals may recognize each other, with juveniles often remaining in family groups until reaching about 60% of adult size, providing them some protection from cannibalistic adults. Communication between dragons involves a sophisticated combination of chemical cues, body postures, and physical displays that regulate social interactions and reduce potentially deadly conflicts. Young dragons exhibit vastly different behavior from adults, spending much of their early years in trees to avoid predation—including from larger members of their own species.

Longevity and Life Cycle

Komodo dragons boast impressive lifespans that exceed most other reptile species, with individuals in captivity regularly living 25-30 years and some exceptional specimens reaching beyond 50 years of age. Their life cycle begins with a precarious hatching period, where young dragons measuring only 12-14 inches must immediately climb trees to avoid predation from adults, including their own parents. These juvenile dragons spend much of their first few years in arboreal habitats, feeding primarily on small lizards, birds, and insects until they reach sufficient size to compete on the ground. Growth rates are relatively rapid during the first five years, with dragons gaining approximately one foot in length annually until reaching sexual maturity. Males typically mature around 8-9 years of age, while females become reproductively active slightly earlier at 7-8 years. Throughout their lives, Komodo dragons continue to grow, albeit at a slower rate after reaching maturity, with the largest individuals generally being the oldest members of the population.

Conservation Status and Threats

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies Komodo dragons as vulnerable, with a total wild population estimated at fewer than 6,000 individuals across their limited island habitat. The primary threats facing these magnificent reptiles include habitat loss due to human development, decreased prey availability, poaching, and the potential impacts of climate change on their island ecosystems. Tourism, while bringing essential conservation funding, also presents challenges including habitat disturbance and potential habituation of dragons to human presence. Rising sea levels present a particularly concerning long-term threat, as much of the dragons’ coastal habitat could be compromised in coming decades. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection within Komodo National Park, strict regulation of tourism activities, anti-poaching measures, and ongoing research to better understand population dynamics. International breeding programs in zoos worldwide maintain genetic diversity and serve as insurance populations should wild numbers continue to decline.

Cultural Significance and Human Relationships

Komodo dragons hold profound cultural significance for local Indonesian communities, featuring prominently in folklore and origin stories of people living on and around their native islands. According to one prevalent legend, a local princess gave birth to twins—one human and one dragon—with the dragon descendant becoming the ancestor of all Komodo dragons, establishing a spiritual kinship between humans and these impressive reptiles. Local communities traditionally maintained a respectful distance from the dragons, viewing them with a mixture of reverence and fear, while developing practices that allowed for coexistence. Today, Komodo dragons represent a vital economic resource through ecotourism, providing employment opportunities for local guides, park rangers, and hospitality workers throughout the region. The complex relationship between dragons and humans continues to evolve as conservation priorities, local economic needs, and cultural traditions intersect in this unique island ecosystem.

Scientific Significance and Research Frontiers

Komodo dragons remain at the forefront of numerous scientific research efforts, offering unique insights into evolutionary biology, venom development, and reptile physiology. Their isolated evolution provides researchers with a living laboratory to study island biogeography principles first proposed by Alfred Russel Wallace, who explored the region in the 19th century. Current research focuses on understanding the complex composition of their venom and potential applications in medicine, particularly compounds that might lead to new anticoagulant medications or treatments for blood clotting disorders. Genetic studies continue to reveal fascinating adaptations, including immune system components that may explain how Komodo dragons resist infection from their own bacteria-laden mouths. Behavioral ecologists employ GPS tracking, camera traps, and other non-invasive technologies to document previously unknown aspects of dragon behavior, movement patterns, and territorial dynamics. Each new discovery about these remarkable reptiles not only enhances our understanding of their biology but also contributes to broader scientific knowledge about adaptation and evolution.

The Komodo dragon stands as one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary success stories—a living relic that offers glimpses into prehistoric times while facing distinctly modern threats. From their deadly hunting abilities to their complex social behaviors, these magnificent reptiles continue to surprise researchers with their adaptations and resilience. As we work to protect their future through conservation efforts, scientific research, and sustainable tourism practices, we ensure that future generations will have the opportunity to marvel at these extraordinary creatures. The dragon’s story reminds us of the remarkable diversity of life on our planet and the importance of preserving even the most seemingly formidable species, whose existence remains precarious in our rapidly changing world. In the ancient eyes of the Komodo dragon, we see reflected both our fascination with the natural world and our responsibility to protect its most unique inhabitants.

Leave a Reply