Ball pythons, scientifically known as Python regius, have captivated both wildlife enthusiasts and pet owners alike with their docile temperament and fascinating behaviors. As one of the most popular reptile pets worldwide, these snakes lead dramatically different lives depending on whether they exist in their natural habitat in West and Central Africa or in human homes across the globe. This exploration of ball pythons in wild versus captive settings reveals striking contrasts in everything from their lifespan and diet to their behavioral patterns and health challenges. Understanding these differences not only enriches our appreciation of these remarkable reptiles but also helps improve welfare standards for captive specimens while informing conservation efforts for wild populations.

Natural Habitat vs. Artificial Enclosures

In their natural environment, ball pythons inhabit the grasslands, savannas, and sparse woodlands of West and Central Africa, primarily in countries like Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria. These pythons spend much of their time in abandoned rodent burrows or termite mounds, which provide ideal microclimates with stable temperatures and humidity levels. Wild ball pythons navigate complex ecosystems spanning several square kilometers throughout their lifetime, experiencing seasonal variations that trigger natural behaviors like breeding and brumation. In contrast, captive ball pythons typically live in glass terrariums or plastic enclosures measuring just a few square feet, with artificial heat sources, manufactured hides, and synthetic substrates attempting to mimic aspects of their natural environment. While modern captive setups increasingly incorporate naturalistic elements like bioactive substrates and varied topography, even the most elaborate enclosures cannot fully replicate the complexity and scope of a wild python’s territory.

Lifespan Differences

One of the most dramatic differences between wild and captive ball pythons lies in their average lifespan. In their natural habitat, ball pythons typically live between 10-15 years, facing numerous threats including predation, disease, parasites, habitat destruction, and hunting by humans. The mortality rate for young wild pythons is particularly high, with many not surviving their first year. Captive specimens, however, regularly live 20-30 years, with exceptional individuals documented reaching 40+ years when provided with optimal care. This dramatic longevity increase results from consistent access to veterinary care, absence of predators, controlled environments that eliminate weather extremes, and regular feeding schedules that prevent starvation. The controlled conditions of captivity effectively remove many of the natural selection pressures that would typically limit a wild python’s lifespan.

Dietary Patterns and Hunting Behaviors

Wild ball pythons are opportunistic ambush predators that may go weeks or even months between successful hunts, displaying remarkable adaptability to food scarcity. Their natural diet primarily consists of small mammals such as African soft-furred rats, gerbils, and occasionally birds, which they detect using heat-sensing pits located around their mouths. These pythons employ complex hunting behaviors, including patiently waiting for prey to pass by before striking with remarkable precision, then constricting their prey before consuming it whole. Captive ball pythons, conversely, typically receive pre-killed rodents on a regular schedule, usually every 7-14 days for adults, eliminating both the feast-or-famine pattern and the need to hunt. This predictable feeding regimen often leads to captive specimens becoming significantly heavier than their wild counterparts, as they receive consistent nutrition without expending energy on hunting. Some owners attempt to simulate hunting behaviors by providing environmental enrichment, though this can only partially replicate the complex prey-acquisition behaviors exhibited in the wild.

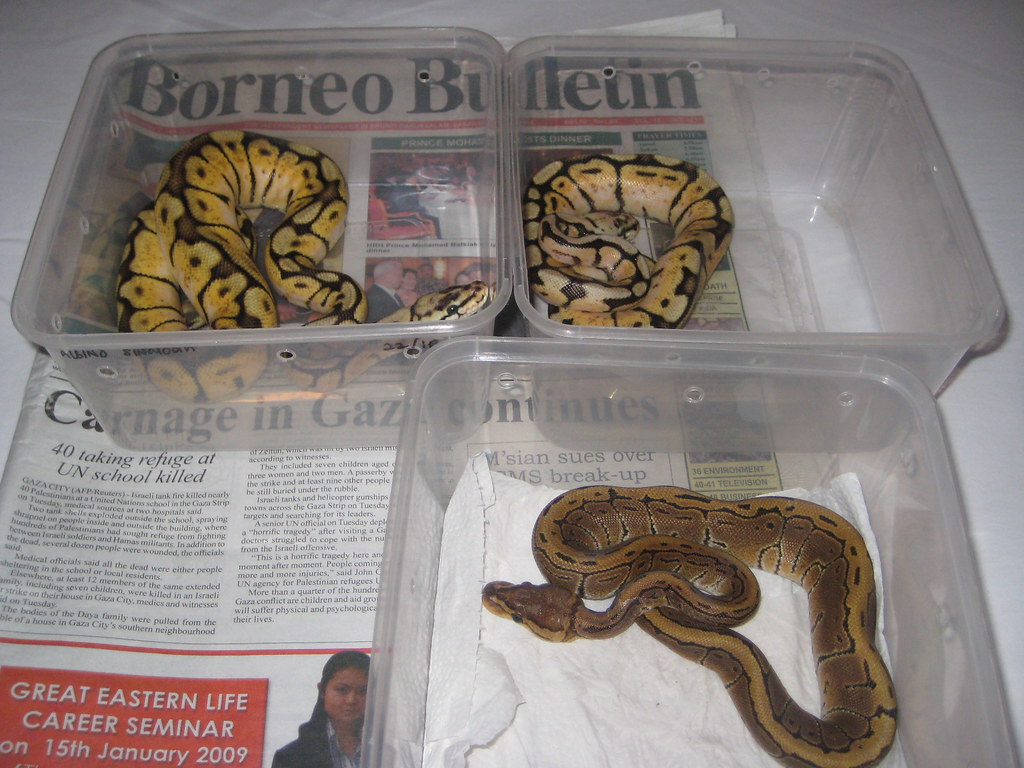

Physical Appearance and Morphology

Wild ball pythons display the species’ natural coloration and pattern – a brownish base with lighter brown to golden-yellow irregular blotches bordered by black – a camouflage adaptation perfectly suited to the dappled light of their native grassland habitat. These wild specimens tend to be leaner and more muscularly defined than their captive counterparts, with body composition reflecting the physical demands of their natural lifestyle. Captive breeding programs, particularly over the last three decades, have produced over 4,000 distinct “morphs” or genetic color and pattern variations that would rarely or never occur in wild populations. These include dramatic variations like albino, axanthic, piebald, and complex combinations that can make captive specimens virtually unrecognizable compared to their wild ancestors. Additionally, captive ball pythons often develop different body proportions, typically carrying more body fat and sometimes growing larger overall due to consistent feeding and reduced activity levels in confined spaces.

Behavioral Repertoire and Activity Cycles

Wild ball pythons exhibit a rich behavioral repertoire shaped by evolutionary pressures, including complex thermoregulation behaviors, seasonal activity patterns, and social avoidance mechanisms. These snakes are primarily crepuscular and nocturnal, becoming most active during dawn, dusk, and nighttime hours when temperatures moderate and prey becomes active. During the dry season, wild specimens may enter a period of reduced activity similar to brumation, remaining in burrows for extended periods to conserve energy and moisture. Captive ball pythons, while retaining many instinctual behaviors, display a significantly modified activity pattern influenced by their environment, with many adopting schedules partially synchronized to human activity. Enclosure constraints limit natural movement patterns, with captive specimens unable to undertake the extended exploration and migration behaviors observed in wild populations. Research indicates that captive pythons may compensate for restricted movement opportunities through increased climbing behavior when provided with suitable branches and environmental enrichment, suggesting an adaptive behavioral plasticity in response to their artificial environment.

Reproduction and Breeding Cycles

In their natural habitat, ball pythons breed seasonally, with mating typically occurring at the beginning of the dry season following the rains (October to November). Wild females typically reproduce only every 2-3 years, conserving energy resources between clutches, and are stimulated to breed by natural environmental cues including temperature fluctuations, barometric pressure changes, and seasonal variations in day length. Captive breeding programs have dramatically altered this natural cycle, with many breeders manipulating environmental conditions to induce breeding behavior throughout the year. Specialized techniques like artificial cooling periods (brumation) and controlled light cycles can trigger reproduction outside natural seasons, allowing females to produce clutches annually rather than biennially or triennially. This intensified breeding schedule, while expanding the genetic diversity of captive populations and producing novel morphs, places significant physiological stress on female pythons, potentially contributing to health issues like dystocia (egg-binding) and reproductive exhaustion not commonly observed in wild specimens.

Health Challenges and Disease Profiles

Wild ball pythons face health challenges primarily shaped by their environment and natural selection, including parasitic infections (particularly blood parasites and gastrointestinal nematodes), injuries from predator encounters, and seasonal food scarcity. These pythons have evolved robust immune systems that effectively manage many common pathogens in their native range, with severely ill individuals typically being removed from the population through predation. Captive ball pythons encounter an entirely different disease profile dominated by husbandry-related conditions like respiratory infections from improper humidity, thermal burns from malfunctioning heating equipment, and metabolic bone disease from dietary deficiencies. Infectious diseases like inclusion body disease (IBD) and reptile-specific paramyxovirus can spread rapidly through captive collections but are rarely documented in wild populations. The closed environment of captivity also presents unique challenges like scale rot from consistently damp substrate and obesity-related health issues from overfeeding, problems virtually unknown in wild specimens.

Stress Factors and Adaptation

Wild ball pythons experience stress primarily related to survival pressures – predator avoidance, resource competition, and environmental extremes like flooding or drought. These natural stressors typically elicit adaptive responses that enhance survival, such as seeking deeper burrows during temperature extremes or becoming more cryptic during high predator activity. Captive ball pythons encounter fundamentally different stressors, including handling by humans, exposure to artificial lighting, restricted movement space, and proximity to potential predator species (such as household pets) without escape possibilities. Research indicates that captive reptiles often express stress through behavioral changes including decreased activity, excessive hiding, refusal to feed, and defensive posturing. While many captive ball pythons adapt remarkably well to human care, they remain wild animals with hardwired instincts and responses shaped by millions of years of evolution rather than the relatively brief period of human domestication, making stress management a crucial aspect of responsible captive husbandry.

Conservation Status and Population Trends

Wild ball python populations face increasing pressure from habitat destruction as agriculture and urban development encroach on their native grassland ecosystems throughout West Africa. The pet trade has historically impacted wild populations significantly, with tens of thousands of specimens exported annually from countries like Ghana and Togo throughout the 1990s and early 2000s before captive breeding became widespread. While now listed on CITES Appendix II, which regulates international trade, ball pythons remain vulnerable to poaching and local hunting for bushmeat and traditional medicine markets. Conversely, captive ball python populations are thriving globally, with hundreds of thousands bred annually in the United States alone, creating a sustainable pet trade largely independent of wild collection. This captive breeding success has paradoxically created both conservation challenges and opportunities – reducing pressure on wild populations while simultaneously diminishing financial incentives for habitat preservation in native range countries that previously benefited from sustainable export programs.

Genetic Diversity Considerations

Wild ball python populations maintain substantial genetic diversity through natural selection processes and geographic distribution across multiple countries and habitat types. These natural populations contain genetic adaptations specific to local conditions, including disease resistance, thermal tolerance, and behavioral traits optimized for regional prey availability and predator pressures. The captive pet trade population, while numerically large, stems from a relatively limited founder population, potentially creating genetic bottlenecks despite the visual diversity of available morphs. The selective breeding practices that produce spectacular color and pattern variations often involve intentional inbreeding to isolate and emphasize recessive traits, sometimes resulting in reduced genetic health and the emergence of problematic co-dominant conditions like “spider” and “wobble” syndrome. Conservation-oriented breeding programs are increasingly focusing on maintaining the genetic integrity of wild-type ball pythons, creating assurance colonies that preserve genetic diversity should reintroduction efforts become necessary in regions where wild populations collapse.

Human Interaction and Habituation

Wild ball pythons typically avoid human contact entirely, perceiving humans as potential predators and responding with defensive behaviors including their signature “balling” posture (curling into a tight ball with their head protected in the center), which gives the species its common name. These wild specimens maintain their natural wariness and defensive responses throughout their lives, retreating from human presence whenever possible. Captive-bred specimens, particularly those handled regularly from a young age, can become remarkably habituated to human interaction, often tolerating handling sessions without defensive responses and sometimes even appearing to seek out keeper interaction during enclosure maintenance. This habituation, while convenient for human keepers, represents a significant departure from natural behavioral patterns and may reduce the survival capacity of captive specimens if they were ever released or escaped into the wild. Research indicates that even well-habituated captive reptiles still experience physiological stress responses during handling, though these responses typically diminish in intensity with regular, gentle interaction.

Ethical Considerations of Captivity

The ethics of keeping ball pythons in captivity continues to evolve as our understanding of reptile cognition, emotional states, and welfare needs advances. The traditional view of snakes as simple, instinct-driven animals with minimal welfare requirements has given way to recognition that these reptiles possess complex environmental preferences, exhibit individual behavioral differences, and can experience negative states analogous to stress, fear, and discomfort. Responsible captive husbandry increasingly focuses on providing environmental enrichment that allows expression of natural behaviors, enclosure designs that accommodate full-body movement, and management practices that respect the animal’s biological imperatives. The ethical calculus must weigh the educational and conservation benefits of maintaining captive populations against the inherent limitations that even the most naturalistic captive setting imposes on a wild species. For individually captive-bred specimens that have never known wild existence, well-designed captive environments can provide appropriate welfare when managed by knowledgeable keepers committed to understanding and meeting the species’ complex needs.

Future Directions in Conservation and Husbandry

The future of ball python conservation and captive husbandry appears increasingly interconnected, with promising developments in both spheres. In the wild, conservation organizations are implementing community-based protection programs that incentivize local protection of python habitat through sustainable ecotourism and carefully managed, quota-based collection programs that provide economic alternatives to habitat destruction. Captive husbandry practices continue to evolve toward more naturalistic and welfare-focused approaches, with bioactive substrates, UVB lighting, and species-appropriate environmental complexity becoming standard rather than exceptional. Advanced monitoring technologies now allow researchers to gather unprecedented data on both wild and captive python behavior, thermal preferences, and activity patterns, informing both conservation strategies and husbandry guidelines. As the gap between our understanding of wild and captive ball python needs narrows, a more holistic approach emerges – one that respects the species’ evolutionary history while acknowledging the reality that captive populations will remain a significant part of the species’ global presence for the foreseeable future.

The stark differences between ball pythons in wild versus captive settings reflect the profound impact of environment on every aspect of these remarkable reptiles’ lives. While captivity offers protection from predators and the elements, resulting in dramatically extended lifespans, it simultaneously removes the complex ecological interactions that shape natural behaviors and evolutionary adaptations. The future of this species depends on a balanced approach that protects wild populations in their native habitats while continuing to improve welfare standards for captive specimens. By understanding and respecting the natural history of ball pythons, both conservationists and responsible pet owners can contribute to ensuring these fascinating snakes thrive both in the grasslands of West Africa and in the carefully crafted environments of human care.

Leave a Reply