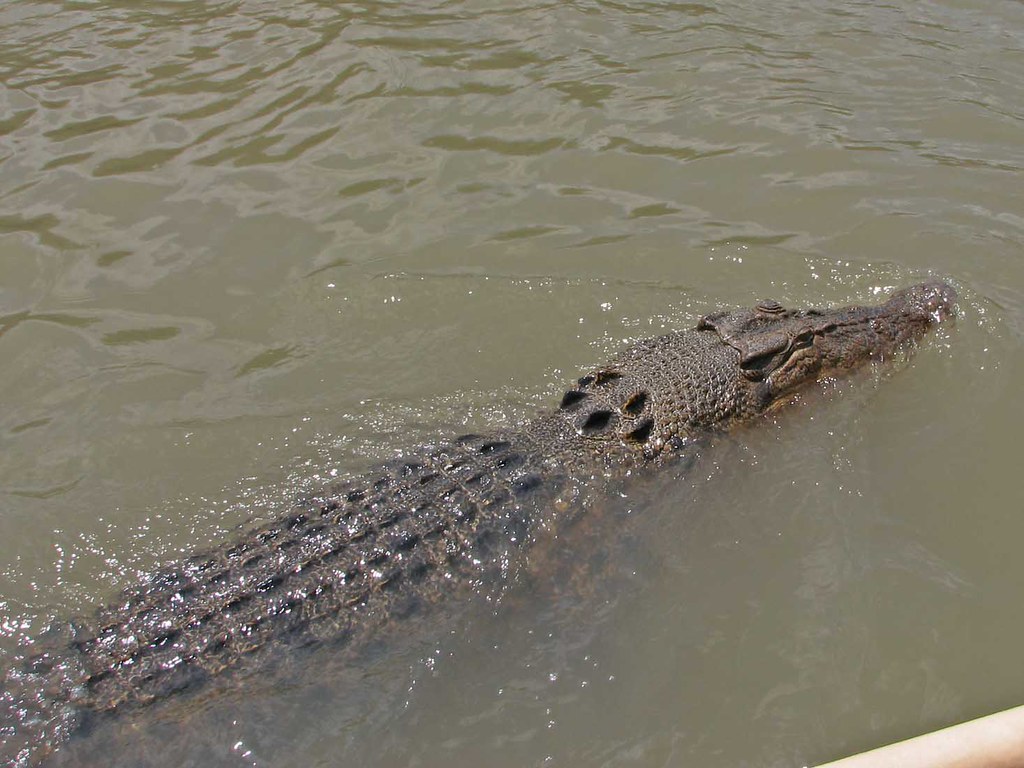

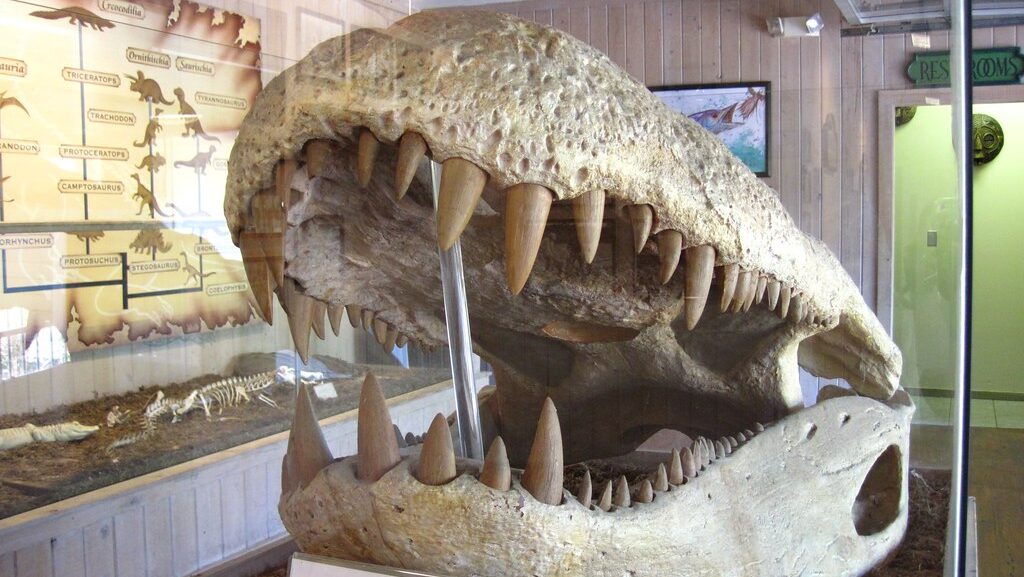

Saltwater crocodiles, the largest living reptiles on Earth, have long captivated scientists and wildlife enthusiasts with their impressive swimming abilities and extensive range throughout the Indo-Pacific region. These ancient predators, known scientifically as Crocodylus porosus, inhabit coastal areas spanning from northern Australia to India and the islands of Southeast Asia. Their presence across such vast geographical areas naturally raises an intriguing question: Can these formidable creatures actually cross oceans? The answer involves fascinating aspects of crocodile physiology, behavior, and documented cases that challenge our understanding of these prehistoric survivors and their remarkable capabilities.

The Remarkable Physiology of Saltwater Crocodiles

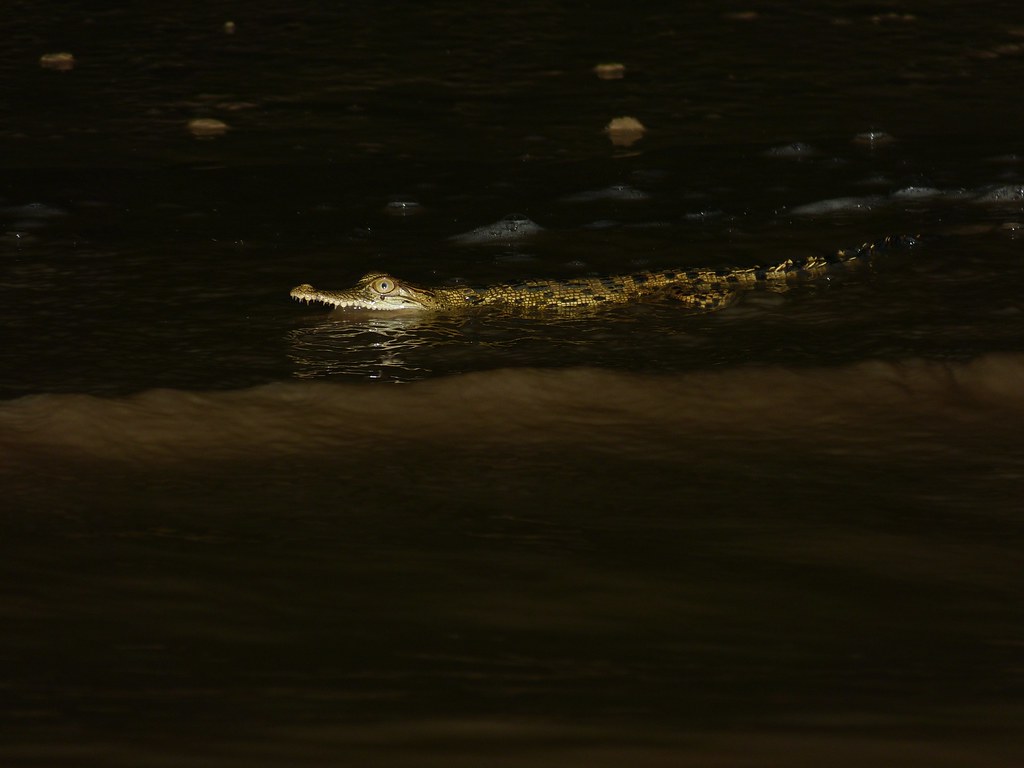

Saltwater crocodiles possess several physiological adaptations that make them exceptionally well-suited for marine travel. Their bodies feature specialized salt glands near the tongue that allow them to excrete excess salt, enabling survival in both freshwater and marine environments. The powerful tail of a saltwater crocodile can propel it through water at speeds of up to 15-18 mph (24-29 km/h) for short bursts, making them an efficient swimmer. Their streamlined bodies, with nostrils and eyes positioned on top of their heads, allow them to remain nearly invisible while swimming. Additionally, their remarkable lung capacity enables them to stay submerged for extended periods—up to an hour when resting—which proves advantageous during long-distance marine journeys.

Swimming Capabilities and Endurance

When it comes to ocean travel, saltwater crocodiles employ a swimming technique known as “body surfing,” where they ride ocean currents while expending minimal energy. Research has shown that these reptiles can maintain a steady swimming pace of 2-3 mph (3-5 km/h) for extended periods, allowing them to cover significant distances. Scientists have documented saltwater crocodiles swimming continuously for days, covering hundreds of kilometers without stopping for rest. Their ability to lower their metabolic rate while swimming contributes significantly to their endurance during these lengthy journeys. Furthermore, their buoyant bodies and the strategic use of ocean currents mean they can travel great distances with relatively little effort.

Documented Long-Distance Journeys

Several well-documented cases provide compelling evidence of saltwater crocodiles’ ocean-crossing abilities. In 2010, a tagged 12-foot male saltwater crocodile was tracked traveling over 250 miles (400 km) in just 20 days from the east coast of Queensland, Australia, to the far northern tip of the continent. Another famous case involved a crocodile nicknamed “Lolong” that was believed to have traveled from Mindanao in the Philippines to Agusan del Sur, crossing significant stretches of open ocean. Perhaps most remarkably, in 2004, researchers documented a saltwater crocodile that traveled over 370 miles (590 km) in 25 days from the east coast of Australia’s Cape York Peninsula through the Torres Strait. These recorded journeys demonstrate the species’ undeniable capacity for significant marine travel.

The Role of Ocean Currents

Ocean currents play a crucial role in facilitating saltwater crocodiles’ long-distance marine journeys. These powerful natural conveyors can dramatically extend the distance a crocodile can travel while conserving energy. In the Indo-Pacific region, currents like the South Equatorial Current and the Indonesian Throughflow create natural highways that crocodiles can exploit for dispersal. Research tracking tagged crocodiles has revealed that they frequently position themselves within these currents, allowing themselves to be carried across considerable distances. Satellite tracking studies have shown that saltwater crocodiles can detect and deliberately enter currents flowing in their preferred direction of travel. This strategic use of ocean currents represents a form of passive transportation that significantly expands their potential range.

Navigation Abilities of Saltwater Crocodiles

How saltwater crocodiles navigate across vast ocean expanses remains one of the more mysterious aspects of their marine journeys. Scientists believe these reptiles may possess a combination of navigational tools, including the ability to detect Earth’s magnetic field for orientation. Recent studies suggest crocodiles might use celestial cues such as the position of the sun or stars to maintain direction during long voyages. Environmental cues like temperature gradients, salinity changes, and even the sound of breaking waves may help guide crocodiles toward landmasses. Their exceptional sensory capabilities, including pressure-sensitive organs that can detect subtle changes in water movement, likely contribute to their navigational prowess across open waters.

Genetic Evidence of Ocean Crossings

Genetic studies provide some of the most compelling evidence for saltwater crocodiles’ ocean-crossing capabilities. DNA analysis of crocodile populations across the Indo-Pacific region reveals genetic similarities between groups separated by hundreds of miles of open ocean, strongly suggesting regular genetic exchange through ocean travel. Research published in the journal Molecular Ecology demonstrated that crocodile populations in northern Australia share genetic markers with those in Papua New Guinea, despite separation by the Torres Strait. Similarly, genetic studies have indicated connections between populations in the Solomon Islands and those in Papua New Guinea, regions separated by over 900 kilometers of open ocean. These genetic findings provide convincing evidence that ocean crossings occur frequently enough to maintain genetic connectivity between distant populations.

Limitations on Ocean Travel

Despite their impressive capabilities, saltwater crocodiles do face significant limitations and challenges when crossing oceans. Exposure to rough seas and strong adverse currents can exhaust even the most robust individuals, potentially leading to drowning. Extended periods without access to freshwater can cause dehydration, as their salt glands have physiological limits to salt excretion. Predation risks from large sharks, particularly for juvenile crocodiles, represent another serious threat during ocean crossings. Temperature fluctuations in open water can also challenge these reptiles, as they rely on external heat sources to maintain optimal body temperature for swimming efficiency and metabolic functions.

The Colonization of Pacific Islands

The presence of saltwater crocodiles on remote Pacific islands provides compelling evidence of their ocean-crossing abilities. Historical and fossil records indicate that these reptiles have colonized islands like the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Fiji long before human transportation could have introduced them. These islands are separated from mainland populations by hundreds of kilometers of open ocean, making natural dispersal the most plausible explanation for their presence. Archaeological evidence suggests that saltwater crocodiles arrived on some Pacific islands thousands of years ago, establishing breeding populations that persisted until relatively recent times. The distribution pattern of crocodiles across these island chains aligns with prevailing ocean currents, further supporting the theory of natural oceanic dispersal.

Age and Gender Differences in Ocean Travel

Not all saltwater crocodiles demonstrate equal propensity for ocean journeys, with significant variations based on age and sex. Adult males, particularly during breeding seasons when competition for territory is intense, are most frequently documented making long-distance ocean voyages. Tracking studies show that males between 10-16 feet (3-5 meters) in length undertake the majority of recorded long-distance marine travels. Younger crocodiles, while more vulnerable to predation, can be involuntarily displaced during storm events, sometimes resulting in unintentional ocean journeys. Female saltwater crocodiles generally demonstrate more sedentary behavior, typically remaining closer to established territories, especially during nesting seasons when they guard their eggs and young.

Historical Reports and Cultural Significance

Historical accounts from maritime cultures across the Indo-Pacific region contain numerous references to saltwater crocodiles encountered far from shore. Indigenous peoples of northern Australia, Papua New Guinea, and various Pacific islands incorporate ocean-traveling crocodiles into their oral traditions and mythologies, suggesting long-standing awareness of this behavior. European colonial records from the 18th and 19th centuries include accounts of crocodiles spotted in open ocean, sometimes hundreds of miles from the nearest land. These historical observations gain credibility when considered alongside modern scientific evidence. Traditional ecological knowledge from coastal communities often includes specific information about crocodile movement patterns that align with contemporary tracking data, providing valuable historical context for current research.

Implications for Conservation and Management

The ocean-crossing abilities of saltwater crocodiles have significant implications for their conservation and management across international boundaries. Their capacity to travel between countries creates challenges for consistent protection policies, as crocodiles regularly cross jurisdictional boundaries with different management approaches. Conservation strategies must account for this mobility, particularly when reintroducing crocodiles to areas where they were previously extirpated. The genetic connectivity maintained through ocean travel has helped prevent inbreeding depression in some isolated populations, highlighting the ecological importance of these journeys. Wildlife managers increasingly recognize the need for international cooperation in crocodile conservation, developing transboundary agreements that acknowledge the species’ mobile nature.

Future Research Directions

Scientists continue to develop new research methods to better understand the ocean-traveling capabilities of saltwater crocodiles. Advanced satellite tracking technologies with longer battery life and more precise GPS capabilities are allowing researchers to monitor crocodile movements across greater distances and time periods. Genomic studies comparing the DNA of different populations provide insights into historical patterns of dispersal and colonization across ocean barriers. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling in marine environments may eventually help detect the presence of traveling crocodiles without direct observation. Interdisciplinary research combining oceanography, animal behavior, and physiology promises to reveal more about how these ancient reptiles navigate across vast oceanic expanses, potentially uncovering navigational abilities previously unknown to science.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear and compelling: saltwater crocodiles can and do travel across significant stretches of ocean. Through a remarkable combination of physiological adaptations, swimming endurance, strategic use of ocean currents, and sophisticated navigation abilities, these prehistoric predators have demonstrated an exceptional capacity for marine dispersal. While they may not regularly cross entire oceans in the manner of marine mammals or seabirds, their documented journeys of hundreds of kilometers through open water represent a significant evolutionary advantage that has contributed to their widespread distribution throughout the Indo-Pacific region. As research techniques continue to advance, we will likely discover even more about the remarkable ocean-traveling capabilities of these ancient reptiles, further expanding our understanding of one of nature’s most successful and enduring predators.

Leave a Reply