Herpetologists, wildlife researchers, and snake enthusiasts face unique occupational hazards that few other professionals encounter. Among these, venomous snake bites represent one of the most serious risks. Despite extensive training and proper handling techniques, even experienced professionals can find themselves on the receiving end of a venomous strike. While prevention remains the best strategy, knowing how to respond in those critical minutes following a bite can mean the difference between life and death. This comprehensive guide outlines essential first aid techniques, common misconceptions, and preparedness strategies specifically tailored for those who work with venomous snakes professionally or encounter them regularly in fieldwork.

Understanding the Gravity of Venomous Bites

Venomous snake bites are serious medical emergencies that require immediate attention, even for experienced herpetologists who might be tempted to downplay their severity. Globally, snakebites cause approximately 81,000-138,000 deaths annually, with many more victims suffering permanent disabilities and tissue damage. The venom’s effects vary dramatically depending on the snake species, ranging from predominantly cytotoxic (tissue-destroying) venoms found in vipers to neurotoxic venoms common in elapids that attack the nervous system.

The quantity of venom injected, known as venom load, can vary significantly even within the same species, with some bites delivering no venom at all (dry bites), while others may deliver a massive, life-threatening dose. Understanding the specific venomous species in your working area and their particular venom profiles should be considered essential knowledge for any professional herpetologist.

Essential First Aid Kit Components

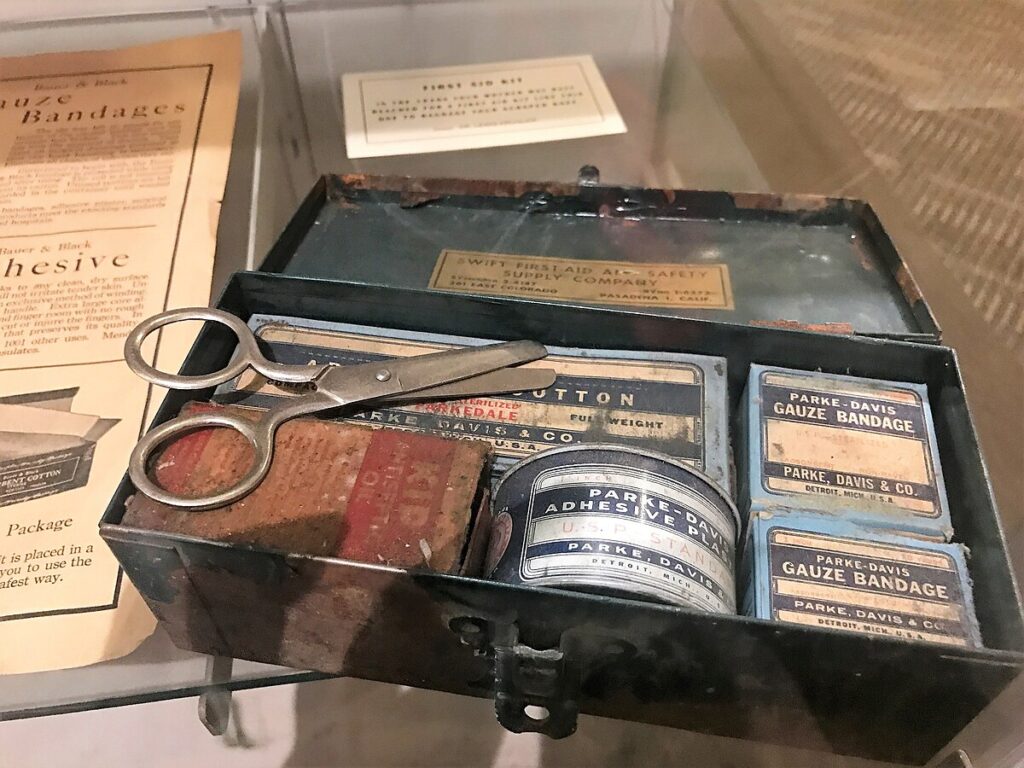

Every herpetologist should maintain a specialized snake bite first aid kit that goes beyond standard medical supplies. This kit should include pressure bandages (elastic bandages 7-10cm wide) for compression-immobilization technique, a permanent marker for marking the bite site and tracking swelling progression, a suction removal device (though these have limited effectiveness), a small timer or watch for monitoring vital signs, and basic wound care supplies.

Additionally, include a snake bite-specific information card with emergency contacts, nearest hospitals with antivenom, and the species of venomous snakes in your working area. Emergency communication devices like satellite phones or personal locator beacons are essential when working in remote locations where cell service may be unavailable. This specialized kit should be compact enough to carry during fieldwork but comprehensive enough to manage the critical period before reaching medical care.

Immediate Actions Following a Bite

The moments immediately following a venomous snake bite are critical and require calm, decisive action. First, move away from the snake to prevent additional bites, which often deliver more venom than the initial strike. Remove any constrictive items like rings, watches, or tight clothing from the affected limb before swelling begins, as these can become dangerous as tissue expands. Position the victim so the bite site is below heart level to potentially slow venom spread, though this remains somewhat controversial among experts.

Call emergency services (911 in the US) immediately, clearly communicating that a venomous snake bite has occurred, as this may affect which hospital you’re directed to based on antivenom availability. If working in remote areas, begin evacuation procedures immediately while implementing appropriate first aid measures – the clock starts ticking from the moment of envenomation.

The Pressure-Immobilization Technique

The pressure-immobilization technique (PIT) is the currently recommended first aid approach for many elapid snake bites (coral snakes, mambas, kraits, and cobras), which primarily deliver neurotoxic venom. This method involves wrapping the affected limb with an elastic bandage, starting at the bite site and continuing up the limb with the same pressure you’d apply for a sprained ankle – firm but not tight enough to cut off circulation.

After bandaging, the limb should be immobilized with a splint or improvised alternative to prevent muscle movement that could accelerate venom circulation. This technique works by trapping the venom in the bite area and limiting its spread through the lymphatic system. Importantly, PIT is not recommended for vipers and pit vipers (rattlesnakes, copperheads) whose cytotoxic venom can cause increased tissue damage if concentrated in one area, highlighting why species identification is crucial for appropriate first aid.

What NOT To Do After a Snake Bite

Dangerous myths about snake bite first aid persist despite scientific evidence, and knowing what not to do is as important as knowing proper techniques. Never cut into the bite site or attempt to suck out venom, as this increases infection risk, damages tissue, and doesn’t effectively remove venom. Avoid applying tourniquets that completely cut off blood flow, as this can lead to limb loss and concentrates tissue-destructive venom in one area.

Electric shock treatments, popularized by some survival shows, have no scientific basis and waste precious time while potentially causing additional harm. Additionally, avoid applying ice to the bite site, as this can increase tissue damage, and don’t administer pain medications like aspirin or ibuprofen, which may worsen bleeding problems associated with some venoms. Most importantly, don’t delay seeking medical care to try traditional remedies or wait to see if symptoms develop – all venomous bites require immediate professional treatment.

Identifying the Snake Safely

Identifying the snake species responsible for a bite provides valuable information for medical personnel determining appropriate antivenom and treatment protocols. If possible, take a clear photograph of the snake from a safe distance using your phone or camera, but never attempt to capture, kill, or handle the snake after a bite, as this risks additional bites and wastes crucial time.

If the snake has been killed previously (not recommended), it can be brought to the hospital for identification, but transport it safely in a sealed container and never handle it with bare hands, as recently dead venomous snakes can still deliver venom through a reflex bite. Many herpetologists working with known species will have already identified the potential threats in their work area and can provide species information to medical staff without needing physical evidence. Remember that accurate description of markings, size, and behavior can help with identification when physical evidence isn’t available.

Monitoring and Documenting Symptoms

Careful monitoring and documentation of developing symptoms provide crucial information for medical personnel upon arrival at a healthcare facility. Use a permanent marker to circle the bite site and mark the leading edge of swelling every 15-30 minutes, writing the time next to each mark to track progression rate. Document vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure (if equipment is available), and respiratory rate at regular intervals.

Note the timing and nature of any symptoms that develop, such as numbness, tingling, metallic taste, muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, nausea, or visual disturbances. Take photos of the progression of any visible symptoms like swelling, discoloration, or blistering, as this visual timeline can be valuable for medical evaluation. This detailed documentation not only assists medical staff but also helps determine if the bite was “dry” (without venom) or how severe the envenomation might be.

Transportation Considerations

How a snake bite victim is transported to medical care significantly impacts their outcome and requires careful planning, especially in field situations. If possible, have someone else drive while the victim remains as still as possible to slow venom circulation – never allow the victim to drive themselves, even if they initially feel fine, as symptoms can develop suddenly. Position the victim so the bitten extremity can remain below heart level during transport.

If in remote areas where vehicle access is limited, consider helicopter evacuation for venomous bites, and ensure your field protocols include predetermined emergency extraction plans. When working in isolated locations, carrying a satellite phone or personal locator beacon should be standard practice, as cellular coverage is often unreliable. Always call ahead to your destination hospital if possible, as this allows the emergency department to prepare appropriate antivenom and assemble specialists who may be needed for your case.

Antivenom: What Herpetologists Should Know

Antivenom remains the definitive treatment for venomous snake bites, and herpetologists should understand its basics even though administration occurs in medical settings. Antivenoms are produced by immunizing animals (typically horses or sheep) with snake venom, then harvesting and purifying the antibodies they produce in response. Different antivenoms target specific snake species or groups, which is why accurate snake identification is crucial for treatment.

Potential adverse reactions to antivenom include anaphylaxis and serum sickness, though modern antivenoms have improved safety profiles compared to older formulations. Herpetologists working with exotic species should research antivenom availability in their region before beginning work, as hospitals typically stock only antivenoms for local species. Those working with rare or exotic venomous species should consider establishing relationships with poison control centers and specialized toxicologists before an emergency occurs, potentially even carrying appropriate antivenom information cards with procurement details for emergency personnel.

Psychological Aspects of Snake Bites

The psychological impact of venomous snake bites is often overlooked but can be significant for both the victim and witnesses. Anxiety and panic can accelerate heart rate and blood pressure, potentially increasing venom circulation, so maintaining calm is both a psychological and physiological necessity. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is not uncommon following severe envenomations, with victims experiencing flashbacks, anxiety around snakes, or even career reconsideration if the bite occurred during professional activities.

Professional herpetologists may experience complicated emotions including embarrassment or perceived professional failure following a bite, which can delay seeking treatment or acknowledging the severity of the situation. Creating a non-judgmental professional culture that views bites as serious occupational hazards rather than mistakes can help ensure prompt reporting and treatment. Support groups specifically for herpetologists who have experienced bites exist and can provide valuable peer support during recovery.

Prevention: The Best First Aid

While knowing proper response techniques is essential, prevention remains the most effective approach to snake bite management among professionals. Always use appropriate handling tools such as snake hooks, tongs, and tubes rather than bare hands when working with venomous species, regardless of experience level. Wear protective clothing including snake gaiters or boots when working in field conditions with venomous species, particularly in dense vegetation where visibility is limited.

Maintain strict protocols for venomous snake housing in captive settings, including secondary containment, secure locking systems, and clear labeling of all venomous enclosures. Never work alone with venomous species; the buddy system ensures someone is available to provide emergency assistance and contact medical services if needed. Regular practice of emergency protocols with colleagues creates muscle memory that can overcome panic in actual emergency situations, making responses more automatic when seconds count.

Field Research Safety Protocols

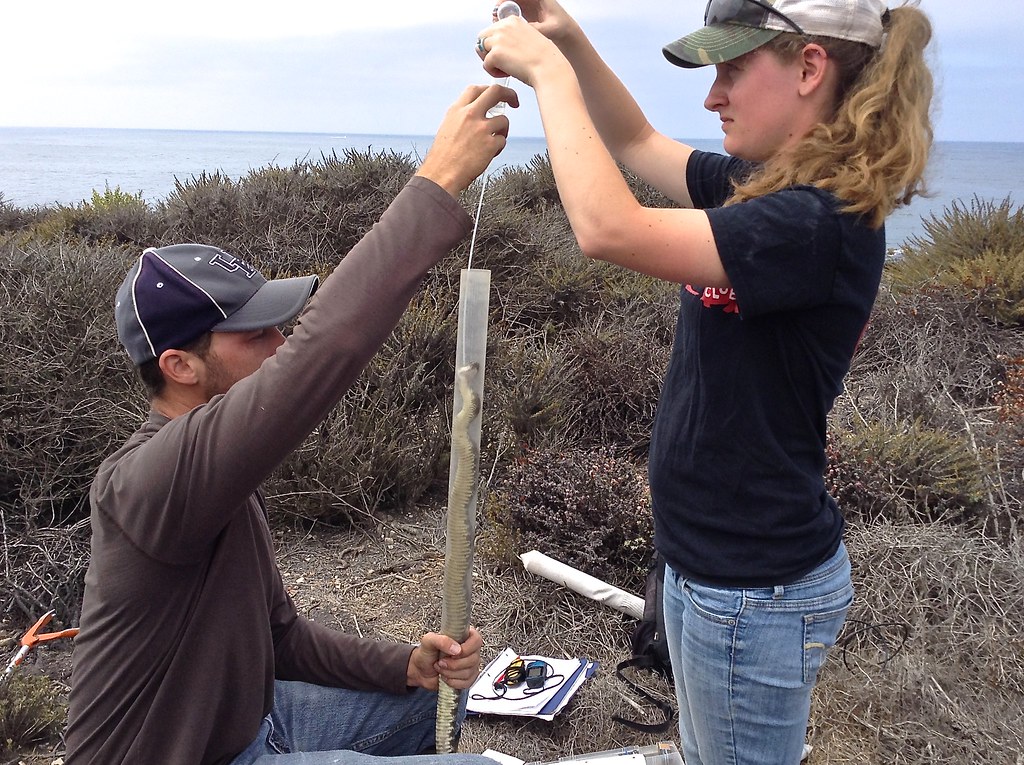

Field herpetologists face unique risks that require specialized safety protocols beyond standard first aid knowledge. Before beginning fieldwork in any new area, research the venomous species present, their behaviors, preferred habitats, and the specific symptoms their venoms produce. Establish communication check-in schedules when working in remote locations, ensuring someone knows your exact location and expected return time. Carry multiple communication devices with different technologies (satellite phone, personal locator beacon, cell phone) to ensure redundancy in emergency situations.

Map the nearest medical facilities with antivenom capabilities before beginning work, including helicopter landing zones if in very remote areas. Consider advanced wilderness first aid training specifically addressing envenomation scenarios for all team members, not just project leaders. These preventative measures should be documented in a formal safety plan that all field team members review before beginning work.

Recovery and Return to Work Considerations

Recovery from a venomous snake bite can be a lengthy process that extends well beyond the initial hospital stay, with implications for when and how a herpetologist returns to working with snakes. Physical recovery may involve physical therapy to restore function to damaged tissues, particularly with cytotoxic venoms that cause tissue necrosis. Psychological readiness should be honestly assessed before handling venomous species again, with many professionals benefiting from a graduated return that begins with non-venomous species to rebuild confidence.

Review the circumstances of the bite with colleagues as an educational opportunity rather than an assignment of blame, identifying system improvements that could prevent similar incidents. Consider temporary accommodations like additional personnel during handling procedures or modified duties while rebuilding both physical capabilities and confidence. Professional herpetologists should recognize that a serious envenomation is both a physical and psychological injury, with both aspects requiring attention during the recovery process.

Training and Preparation for Herpetologists

Comprehensive training should be a prerequisite for any professional working with venomous snakes, going well beyond basic first aid knowledge. Seek formal venomous snake handling courses taught by experienced professionals, which often include mock emergency scenarios to practice response under stress.

Regularly practice emergency protocols with colleagues, including pressure-immobilization technique application, emergency contact procedures, and evacuation strategies relevant to your working environment. Consider advanced certifications in wilderness first aid or wilderness first responder training, which address medical emergencies in remote settings where definitive care may be hours away.

Establish relationships with local emergency departments and poison control centers before emergencies occur, potentially arranging educational exchanges where herpetologists provide snake identification training to medical staff while learning about medical treatment protocols. This proactive approach to training creates a foundation of preparedness that can significantly improve outcomes when real emergencies occur.

For herpetologists and those who work with venomous snakes, the risk of bites represents an occupational hazard that requires serious preparation. By understanding proper first aid techniques, avoiding dangerous myths, and developing comprehensive emergency protocols, professionals can significantly improve outcomes when bites occur.

Remember that even the most experienced handlers can experience a bite, and having the knowledge to respond appropriately is not an admission of carelessness but rather a demonstration of professional responsibility. The field of herpetology continues to advance our understanding of these remarkable animals, and with proper safety measures, the risks associated with this important work can be managed effectively. Your expertise in venomous species makes you uniquely qualified to be your own best first responder – an advantage that could one day save your life or the life of a colleague.

Leave a Reply