Reptiles represent some of the most endangered vertebrates on our planet, with approximately 21% of species currently facing extinction risks. Behind the scenes at modern zoos and aquariums, dedicated professionals are working tirelessly on breeding programs that offer hope for threatened reptile species.

These institutions have evolved far beyond their entertainment origins to become critical conservation centers that combine scientific research, captive breeding expertise, and habitat preservation efforts. This article explores how zoos contribute to reptile conservation through carefully managed breeding initiatives and reintroduction programs that are helping to restore wild populations of turtles, lizards, snakes, and crocodilians worldwide.

The Evolution of Modern Zoos as Conservation Centers

The modern zoo bears little resemblance to the menageries of exotic animals displayed purely for entertainment in previous centuries. Today’s accredited zoological institutions operate with conservation missions at their core, functioning as sophisticated research facilities and genetic safeguards for endangered species. Many have established dedicated herpetology departments with specialized staff who understand the complex reproductive requirements of various reptile species.

These transformations have positioned zoos as critical players in the fight against biodiversity loss, particularly for reptiles whose conservation needs were historically overlooked compared to more charismatic mammals and birds. The shift toward conservation-focused operations has also brought increased collaboration between zoos, universities, government agencies, and field conservation organizations to create comprehensive recovery strategies for threatened reptiles.

The Reptile Extinction Crisis

Reptiles face unprecedented challenges in the wild, with habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, disease, and illegal collection for the pet trade driving many species toward extinction. Island species are particularly vulnerable, with restricted ranges that provide nowhere to escape from introduced predators or habitat alterations.

Freshwater turtles and tortoises represent one of the most endangered vertebrate groups on Earth, with more than 50% of species threatened with extinction. Climate change poses a unique threat to many reptiles with temperature-dependent sex determination, where warming temperatures can skew sex ratios and potentially lead to reproductive collapse. These combined pressures have created a situation where ex-situ (off-site) conservation breeding in zoos has become essential for numerous reptile species that might otherwise disappear entirely.

Specialized Breeding Facilities and Expertise

Modern zoos have developed specialized breeding facilities that recreate the precise environmental conditions necessary for successful reptile reproduction. These facilities often include climate-controlled rooms where temperature, humidity, light cycles, and even barometric pressure can be adjusted to mimic seasonal changes that trigger breeding behaviors. Some institutions maintain behind-the-scenes areas that are several times larger than their public exhibits, dedicated entirely to conservation breeding programs.

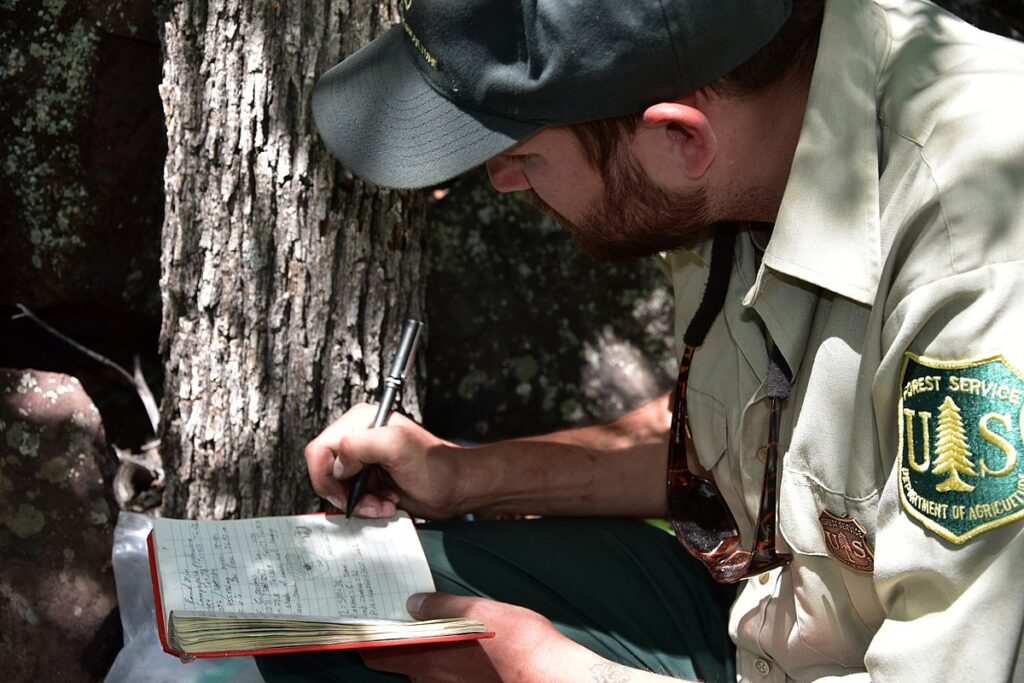

Zoo herpetologists have become experts in determining the specific environmental cues, nutritional requirements, and social dynamics needed to encourage reproduction in challenging species. This collective expertise often represents decades of careful observation and documentation that has transformed our understanding of reptile reproductive biology and established breeding protocols for species that were once considered impossible to propagate in captivity.

Species Survival Plans and Population Management

Coordinated breeding programs like the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Species Survival Plans (SSPs) provide sophisticated genetic and demographic management for reptile populations across multiple institutions. These programs maintain detailed studbooks that track the lineage of every individual animal to maximize genetic diversity and minimize inbreeding in captive populations.

Population managers make specific breeding recommendations each year, sometimes arranging transfers of animals between institutions to create optimal genetic pairings. For critically endangered reptiles, these managed populations serve as genetic reservoirs or assurance colonies that protect against extinction while wild conservation efforts continue. These collaborative programs ensure that limited space in zoological facilities is used efficiently to maintain genetically robust populations of priority species rather than random collections of common reptiles.

Technological Innovations in Reptile Reproduction

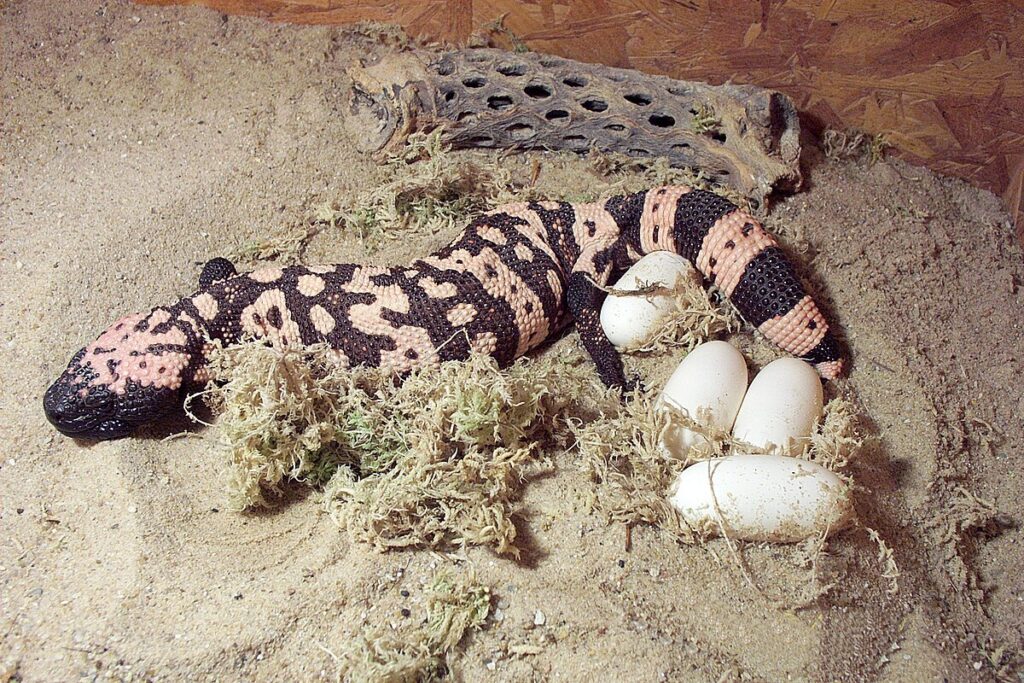

Zoological institutions have pioneered numerous technological innovations that have revolutionized reptile breeding success. Artificial incubation techniques with precise temperature and humidity control have dramatically increased hatch rates for eggs that would face high mortality in natural conditions. Assisted reproductive technologies including artificial insemination, hormone therapy, ultrasound monitoring of egg development, and even genome resource banking (freezing sperm or embryos) are increasingly applied to reptile conservation.

Some institutions have developed specialized X-ray and CT scanning protocols to monitor egg development non-invasively, allowing interventions when complications arise. These technological advances have enabled successful reproduction in species that rarely breed in captivity and provided tools to manage genetic diversity more effectively than would be possible through natural breeding alone.

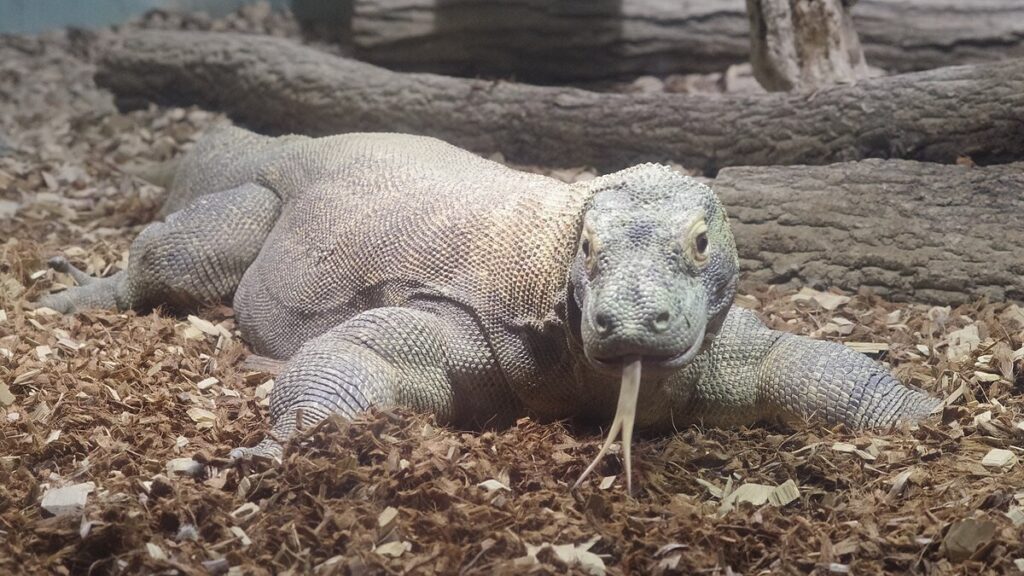

Case Study: The Komodo Dragon Breakthrough

The successful breeding of Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) in zoos represents one of the most significant achievements in reptile conservation. Prior to the 1990s, these largest living lizards rarely reproduced in captivity, but collaborative research across multiple zoos uncovered the complex environmental and social factors required for successful breeding. The species presented unique challenges, including female ability to reproduce through parthenogenesis (virgin birth) in the absence of males, which required careful genetic monitoring.

Zoo breeding programs have now produced multiple generations of Komodo dragons, maintaining genetic diversity in the captive population while researchers study their ecology. This success story demonstrates how zoo-based research can overcome reproductive barriers in challenging species while contributing valuable scientific knowledge about reproductive biology that benefits both captive management and wild conservation efforts.

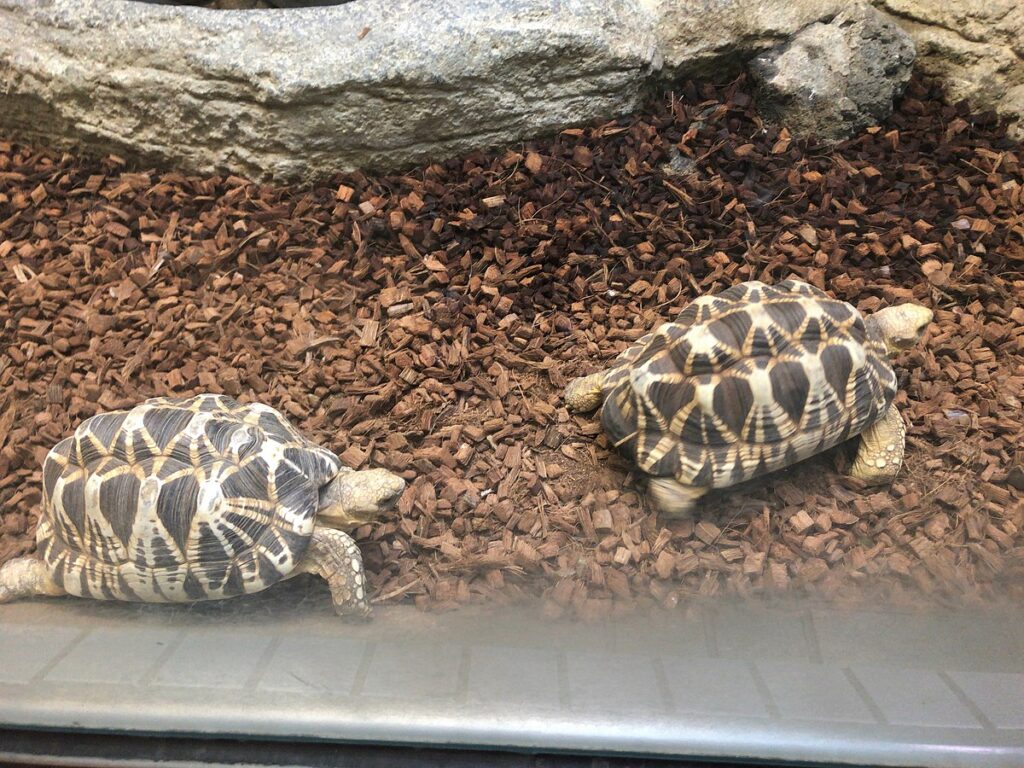

Recovery of Critically Endangered Turtles

Zoos have played pivotal roles in bringing multiple turtle species back from the brink of extinction through intensive breeding programs. The Burmese star tortoise (Geochelone platynota), once functionally extinct in the wild due to overharvesting, has been successfully bred at several zoological institutions, with thousands of offspring now reintroduced to protected areas in Myanmar.

Similar success stories include the Western swamp turtle of Australia, the Jamaican iguana, and various pond turtles from Asia that faced imminent extinction before zoo breeding programs were established. For many freshwater turtle species, these programs represent the last line of defense against extinction as their natural habitats face continuing degradation and poaching pressure. Zoos have also developed “head-starting” programs where eggs or hatchlings collected from vulnerable wild nests are raised in protected settings until they reach sizes less vulnerable to predation before release.

Preparing Reptiles for Reintroduction

Successfully breeding reptiles in captivity is only the first step in conservation; preparing them for reintroduction requires additional expertise. Modern zoo programs incorporate natural behavior encouragement, predator recognition training, and environmental enrichment to ensure captive-bred reptiles develop the skills needed for survival in the wild. Some facilities maintain pre-release conditioning areas where animals can practice natural foraging, thermoregulation, and shelter-seeking behaviors in semi-natural settings.

Health screening protocols have been developed to ensure animals do not introduce diseases to wild populations upon release, with quarantine periods and comprehensive veterinary evaluations before any reintroduction. These preparations reflect the evolution of reintroduction science from earlier approaches that simply released captive-bred animals with little preparation to today’s carefully managed processes designed to maximize survival rates and minimize ecological disruption.

Monitoring Post-Release Success

Zoological institutions remain involved long after reptiles have been reintroduced, employing sophisticated monitoring techniques to track their survival and integration into wild populations. Radio telemetry, GPS tracking devices, passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags, and even environmental DNA sampling are commonly used to monitor released animals without causing stress through recapture. Long-term population monitoring allows conservationists to assess whether reintroduced animals are surviving, reproducing, and establishing self-sustaining populations.

These monitoring programs often continue for decades, generating valuable data that helps refine future reintroduction efforts and habitat management strategies. The feedback loop between monitoring results and breeding program adjustments has proven essential for improving reintroduction success rates over time as lessons learned from each release inform subsequent conservation actions.

Habitat Protection and Restoration

Zoos increasingly recognize that successful reintroduction requires healthy ecosystems, leading many institutions to invest directly in habitat protection and restoration at release sites. These efforts often include purchasing land for conservation, funding protected area management, removing invasive species, restoring native vegetation, and working with local communities to reduce threats to reintroduced reptiles.

The Wildlife Conservation Society, linked to several major zoos, manages millions of acres of protected habitat worldwide that provides release sites for captive-bred reptiles. By addressing the original causes of population declines, these habitat-focused investments significantly improve the chances that reintroduced reptiles will establish viable populations. This holistic approach recognizes that breeding programs must be paired with field conservation to achieve lasting success in reptile recovery.

Community Engagement and Education

Successful reptile reintroduction programs almost always depend on support from local communities, making education and engagement critical components of zoo conservation strategies. Many zoos have established outreach programs in reintroduction areas that employ local staff, provide conservation education in schools, and develop alternative livelihoods to reduce pressures on reptile populations.

These initiatives help transform local attitudes toward often-feared reptile species by highlighting their ecological importance and cultural significance. In many cases, former poachers have been recruited as conservation rangers, applying their intimate knowledge of reptile behavior to protection efforts. By building local pride in endemic reptile species and demonstrating economic benefits from conservation, these community engagement programs create sustainable protection for reintroduced populations that continues long after zoo staff have departed.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite their successes, reptile breeding and reintroduction programs face significant challenges and ethical questions that require careful consideration. There are ongoing debates about whether limited conservation resources should focus on captive breeding or habitat protection, with some conservationists arguing that ex-situ programs divert attention from addressing root causes of decline. Genetic concerns include founder effects in captive populations started with few individuals, adaptation to captivity that reduces wild survival traits, and potential introduction of maladaptive genes into wild populations. Welfare considerations are increasingly prominent, with questions about whether certain species with complex needs can thrive in captive settings regardless of environmental enrichment efforts. These challenges have prompted many zoological institutions to develop ethical frameworks specifically addressing conservation breeding and reintroduction, with greater transparency about decision-making processes and outcome measurements.

Future Directions in Zoo-Based Reptile Conservation

The future of zoo-based reptile conservation looks increasingly sophisticated as new technologies and approaches emerge. Genome banking initiatives are preserving genetic material from threatened reptiles to maintain evolutionary potential even when physical breeding spaces are limited.

Advanced reproductive technologies being developed for mammals are gradually being adapted for reptiles, including potential future applications of cloning for extremely endangered species. Increased collaboration between zoos globally is creating more integrated conservation strategies that combine the strengths of different institutions and regions.

Climate change adaptation is becoming a central focus, with breeding programs beginning to select for heat tolerance and other resilience traits in species facing temperature-related threats. These innovations suggest that zoos will continue evolving as increasingly effective conservation centers for threatened reptiles, maintaining their relevance despite ongoing debates about the ethics of keeping animals in captivity.

Modern zoological institutions have transformed from entertainment venues into sophisticated conservation centers that play critical roles in preventing reptile extinctions worldwide. Through specialized breeding facilities, scientific research, genetic management, and collaborative reintroduction programs, zoos provide essential safety nets for species that might otherwise disappear forever. While challenges remain in balancing ex-situ conservation with field protection efforts, the success stories of species like the Burmese star tortoise and Komodo dragon demonstrate the potential of well-managed breeding programs. As climate change and habitat loss continue to threaten reptile diversity globally, the expertise developed in zoological institutions represents an increasingly valuable resource for conservation. By combining captive breeding with habitat protection, community engagement, and cutting-edge technology, modern zoos have established themselves as indispensable partners in the fight to preserve reptile biodiversity for future generations.

Leave a Reply