The term “dangerous” often evokes feelings of avoidance and fear, particularly when applied to wildlife. Ironically, many of the world’s most potentially lethal animals—those capable of causing human harm or death—find themselves on endangered species lists, creating a complex conservation paradox. This contradiction places conservationists, governments, and local communities in difficult positions as they balance human safety with the preservation of biodiversity. From venomous snakes and predatory big cats to disease-carrying insects and aggressive marine life, these creatures play vital ecological roles despite the threats they may pose to humans. This article explores the multifaceted challenges of protecting potentially dangerous animals facing extinction, examining the ethical, practical, and ecological dimensions of this unique conservation dilemma.

The Paradox of Fearing What We Need to Save

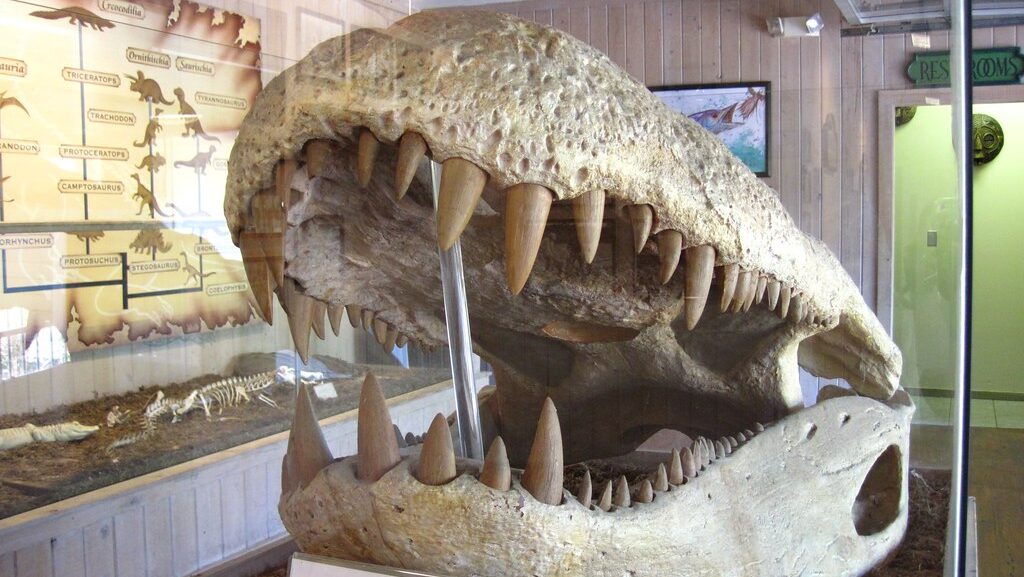

Human psychology naturally inclines us to protect what we find appealing and avoid what we fear, creating a fundamental challenge for conservation efforts focused on dangerous species. Animals like the great white shark, king cobra, or saltwater crocodile trigger instinctive fear responses that make garnering public support for their protection significantly more difficult than for charismatic species like pandas or elephants. This fear-based aversion often translates into reduced funding, public support, and political will for conservation initiatives targeting potentially lethal species. Yet these same feared animals often serve as keystone species in their ecosystems, regulating prey populations and maintaining biodiversity through complex ecological interactions. Their decline or extinction could trigger cascading effects throughout entire ecosystems, demonstrating that ecological importance operates independently of human perceptions of danger.

Top Predators: Beautiful, Deadly, and Disappearing

Large predators like tigers, lions, and polar bears represent some of the most powerful and potentially dangerous animals on Earth, capable of killing humans with relative ease. Despite their lethal capabilities, these apex predators face unprecedented threats from habitat loss, poaching, and human-wildlife conflict, with many species now critically endangered. The tiger, for instance, has lost approximately 95% of its historic range and now numbers fewer than 4,000 individuals in the wild. These apex predators play crucial roles in ecosystem regulation by controlling herbivore populations and influencing prey behavior, creating what ecologists call “landscapes of fear” that prevent overgrazing and maintain habitat diversity. Their disappearance often leads to trophic cascades—ecological chain reactions where herbivore populations explode, vegetation is overgrazed, and numerous other species suffer as a result. The conservation challenge becomes particularly acute when these predators come into contact with human settlements, creating situations where human safety and species preservation appear to be in direct conflict.

Venomous Snakes: Medical Treasure Troves on the Brink

Venomous snakes kill an estimated 100,000 people annually, making them among the deadliest animals for humans worldwide, yet many species face severe population declines due to habitat destruction, persecution, and illegal collection. Species like the king cobra, timber rattlesnake, and many island vipers now appear on threatened and endangered species lists despite their potentially lethal capabilities. Paradoxically, the very venoms that make these reptiles dangerous also contain complex proteins and compounds that have led to breakthrough medications for treating heart disease, chronic pain, and blood disorders.

Captopril, a medication used by millions to treat hypertension, was developed based on peptides found in pit viper venom, while research on cobra venom has yielded important insights into pain management. Conservation efforts must therefore balance legitimate human safety concerns with both the ecological importance of these predators and their untapped potential for medical advancement—a complex calculus that varies dramatically across different regional and cultural contexts.

Sharks: Feared Predators Facing Commercial Extinction

Few animals evoke as much primal fear as sharks, yet despite their fearsome reputation, these ancient predators face catastrophic population declines worldwide, with some species having decreased by over 90% in recent decades. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) now lists over a third of all shark and ray species as threatened with extinction, primarily due to overfishing, finning, and bycatch in commercial fishing operations. Despite causing fewer than ten human fatalities annually worldwide, sharks continue to suffer from negative public perception fueled by sensationalized media coverage and films like “Jaws” that greatly exaggerate their threat to humans.

As apex predators, sharks play critical roles in marine ecosystems by regulating prey populations and maintaining the health of coral reefs and seagrass beds. Their removal has been linked to the collapse of scallop fisheries, degradation of coral reef systems, and destabilization of commercial fish stocks—demonstrating that human fear of these predators has ironically led to outcomes that negatively impact human interests through disrupted marine ecosystems.

Disease Vectors: The Conservation Case for “Pests”

Mosquitoes, ticks, and other disease vectors collectively contribute to millions of human deaths annually through the transmission of malaria, dengue fever, Lyme disease, and other pathogens, creating complex ethical questions about their conservation status. While few people advocate for protecting disease-spreading insects, many of these species have experienced significant population declines due to pesticide use, habitat loss, and climate change, with potential ecological consequences we’re only beginning to understand. Mosquitoes, despite their deadly reputation, serve as important food sources for bats, birds, fish, and amphibians, while also functioning as pollinators for certain plant species.

The challenge for conservation biologists involves determining which vector populations require management versus protection, often needing to consider both public health imperatives and ecological functions simultaneously. This delicate balancing act becomes even more complex when considering that climate change is expanding the range of many disease vectors into new regions, potentially bringing endangered vector species into more frequent contact with human populations unprepared for their associated diseases.

Human-Wildlife Conflict: When Conservation Meets Safety

Human-wildlife conflict represents perhaps the most direct manifestation of the “lethal yet endangered” dilemma, occurring when protected dangerous species threaten human lives, livestock, or livelihoods. In India, endangered tigers and leopards kill dozens of people annually, while African elephants destroy crops and occasionally injure or kill farmers protecting their fields. These situations create impossible choices for conservation managers who must balance the survival needs of threatened species against legitimate human safety concerns and economic interests.

Traditional solutions often relied on lethal control or relocation, but modern conservation approaches increasingly focus on preventative measures like wildlife corridors, predator-proof livestock enclosures, and community-based conservation incentives that share tourism revenues with affected communities. The success of these programs often depends on cultural factors, with some communities showing remarkable tolerance for dangerous wildlife based on religious or cultural values, while others demand immediate removal of any threatening animals regardless of conservation status. These contrasting attitudes demonstrate that effective conservation of dangerous species must incorporate not just biological science but also careful consideration of local cultural contexts and economic realities.

Cultural Perspectives: From Worship to Extermination

Cultural attitudes toward potentially dangerous wildlife vary dramatically across societies, directly influencing conservation outcomes for endangered yet lethal species. In parts of India, sacred beliefs protect deadly king cobras despite their danger, with snake gods like Nāga receiving religious veneration that translates into practical conservation benefits. Conversely, European and colonial American history includes systematic campaigns to eradicate predators like wolves and bears, reflecting cultural narratives that cast these animals as evil or threatening to civilization.

Indigenous perspectives often occupy middle ground, acknowledging the danger of certain species while respecting their ecological and spiritual importance through sustainable management practices developed over generations. These contrasting cultural frameworks demonstrate that successful conservation of dangerous species requires approaches tailored to local cultural contexts rather than one-size-fits-all solutions. Conservation programs that ignore deeply held cultural beliefs—whether those beliefs favor protection or elimination—generally fail to achieve sustainable outcomes for endangered yet dangerous species.

Legal Frameworks: Protection Versus Public Safety

Legal frameworks governing the management of dangerous yet endangered species vary widely across jurisdictions, creating a patchwork of protections and exceptions that reflect the inherent tension between conservation and public safety. The U.S. Endangered Species Act, for instance, provides strong protections for listed species regardless of their potential danger to humans, but includes provisions for “taking” (killing) protected animals in self-defense or to protect human life. International agreements like CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) regulate trade in endangered species but provide exemptions for specimens used in life-saving antivenom production.

Many countries employ “problem animal” policies that allow for removal or elimination of specific dangerous individuals that threaten human communities, even when the species as a whole remains protected. These nuanced legal frameworks attempt to balance conservation imperatives with public safety concerns, but their implementation often generates controversy when high-profile incidents occur, such as when protected predators attack humans or livestock. The resulting legal battles frequently highlight the fundamental difficulty of crafting policies that adequately address both human safety needs and biodiversity conservation goals.

Climate Change: Shifting Ranges and New Dangers

Climate change is dramatically altering the distribution of potentially dangerous wildlife, creating new conservation challenges as species adapt to changing conditions by moving into new territories. Venomous snakes like copperheads are expanding northward in North America as warming temperatures make previously unsuitable habitats viable, bringing them into contact with human populations unaccustomed to their presence. Marine species face similar disruptions, with potentially dangerous jellyfish blooms increasing in frequency and box jellyfish expanding their range into new coastal areas as ocean temperatures rise.

These range shifts complicate conservation efforts as endangered yet dangerous species may require protection in regions where they’re perceived as invasive threats rather than native species requiring conservation attention. Climate adaptation planning for dangerous species must therefore consider not just the biological needs of the animals but also the social and cultural readiness of communities to coexist with unfamiliar dangerous wildlife. This challenge represents a new frontier in conservation biology, requiring interdisciplinary approaches that combine climate science, ecology, and social sciences to develop effective management strategies.

Ecotourism: Transforming Fear into Conservation Revenue

Ecotourism has emerged as a powerful tool for transforming dangerous yet endangered species from perceived liabilities into valuable assets for local communities, creating economic incentives for their protection. Great white shark cage diving in South Africa, tiger safaris in India, and crocodile viewing in Australia generate millions in tourism revenue annually, creating jobs and income streams that depend on the continued existence of these potentially lethal animals.

When local communities receive direct economic benefits from dangerous wildlife, their tolerance for human-wildlife conflict often increases dramatically, creating a financial counterweight to the legitimate safety concerns these animals raise. Successful wildlife tourism operations focused on dangerous species typically implement strict safety protocols and educational components that help transform public perception from fear to fascination and respect. However, these operations must carefully balance visitor expectations for close encounters with the welfare of the animals and genuine safety concerns, as incidents involving tourists can quickly undermine conservation progress and reinforce negative stereotypes about dangerous wildlife.

Technological Solutions: Coexistence Through Innovation

Technological innovations increasingly offer promising pathways for resolving conflicts between human safety and conservation of dangerous species. Early warning systems using GPS collars on predators like tigers and lions can alert nearby communities when these animals approach, allowing for preemptive safety measures rather than reactive lethal control. Innovative deterrents such as flashing LED lights that mimic the movement patterns of multiple predators have shown effectiveness in reducing livestock predation by lions and leopards, addressing a major source of human-wildlife conflict.

Advances in antivenom production have reduced reliance on wild-caught venomous snakes, allowing for more comprehensive protection of endangered venomous species while maintaining human medical needs. Drone monitoring of dangerous marine species like sharks can provide real-time beach safety information while generating valuable scientific data on the movements and behaviors of threatened populations. These technological approaches demonstrate that the traditional dichotomy between human safety and conservation of dangerous species can increasingly be bridged through creative problem-solving and appropriate application of modern tools.

The Ethical Dimensions: Rights, Responsibilities, and Risk

The conservation of lethal yet endangered species raises profound ethical questions about how humans should balance species preservation with human safety and wellbeing. Some environmental ethicists argue that all species have inherent value regardless of their danger to humans, deserving protection based on their intrinsic worth rather than utilitarian calculations of human benefit or risk. Others advocate for more nuanced approaches that prioritize human safety while still making reasonable accommodations for dangerous wildlife, particularly in areas where humans have encroached on traditional animal territories.

The concept of “just risk” enters these discussions, questioning whether all human communities should bear equal risk from dangerous wildlife, or whether wealthy tourists seeking thrilling encounters should be treated differently than subsistence farmers whose livelihoods are threatened by the same animals. Indigenous perspectives often provide valuable ethical frameworks that recognize both the danger and value of lethal wildlife, incorporating respect for these animals while maintaining practical approaches to managing risk. These diverse ethical viewpoints demonstrate that resolving the conservation dilemma of dangerous species requires not just scientific and technical solutions but also careful moral reasoning about our responsibilities to both human communities and threatened wildlife.

Future Directions: Integrated Conservation Approaches

The future of conservation for dangerous yet endangered species likely lies in integrated approaches that acknowledge both the legitimate safety concerns these animals raise and their ecological, scientific, and cultural importance. Successful models increasingly incorporate community-based conservation, where local stakeholders participate directly in decision-making and benefit economically from protection efforts, transforming potentially dangerous wildlife from liabilities into assets. One Health approaches—which recognize the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health—provide frameworks for addressing disease vectors through ecosystem management rather than eradication campaigns.

Advances in genomic conservation may eventually allow for preserving the genetic diversity of dangerous species through biobanking and other ex-situ methods while managing wild populations with human safety in mind. These integrated approaches move beyond the false dichotomy of “humans versus dangerous wildlife” to recognize that human wellbeing ultimately depends on functioning ecosystems that include predators, venomous species, and other potentially dangerous animals. By acknowledging both the risks these species pose and their irreplaceable ecological roles, conservation biology is developing more sophisticated and effective approaches to this unique conservation dilemma.

The conservation of lethal yet endangered species embodies one of the most challenging paradoxes in modern conservation biology. These animals—whether they’re apex predators, venomous creatures, or disease vectors—often trigger instinctive fear responses that complicate protection efforts, yet many play irreplaceable roles in their ecosystems and hold immense scientific and cultural value. Resolving this dilemma requires moving beyond simplistic approaches that either prioritize human safety at all costs or advocate for absolute protection regardless of human impacts. Instead, successful conservation of these species demands nuanced strategies that incorporate community involvement, technological innovation, cultural sensitivity, and ethical reasoning. As we navigate a future shaped by climate change, habitat loss, and increasing human-wildlife interactions, our ability to coexist with dangerous yet endangered wildlife will test not just our scientific understanding but also our capacity for balancing competing values in an increasingly complex conservation landscape.

Leave a Reply