The intelligence of reptiles has long been underestimated by science, with mammals and birds traditionally occupying the spotlight in cognitive research. However, recent studies have begun to challenge our preconceptions about reptilian brains, particularly among venomous and potentially lethal species. From cobras that can recognize their handlers to komodo dragons that can solve complex puzzles, evidence is mounting that some of our most feared reptilian neighbors may possess cognitive abilities far beyond what we previously thought possible. This article explores the fascinating research into reptilian intelligence, with a focus on whether lethal reptiles are indeed getting smarter, or if science is simply becoming better at recognizing intelligence that was there all along.

The Evolution of Reptilian Brain Research

For decades, reptiles were considered primitive creatures with limited cognitive abilities, largely operating on instinct rather than intellect. This assumption stemmed partly from early brain studies that focused on the neocortex—a brain structure abundant in mammals but apparently absent in reptiles. Scientists like Paul MacLean popularized the “triune brain” theory in the 1960s, which portrayed reptilian brains as ancient relics concerned only with basic survival functions. However, modern neuroscience has thoroughly debunked this oversimplified view, revealing that reptiles possess analogous brain structures that serve similar functions to mammalian brain regions associated with complex cognition. This paradigm shift has opened the door to fascinating discoveries about reptilian intelligence, particularly among species traditionally feared for their lethal potential.

Measuring Intelligence in Venomous Snakes

Studying intelligence in venomous snakes presents unique challenges that have historically limited our understanding of their cognitive abilities. The obvious danger associated with handling these animals necessitates special safety protocols that can complicate experimental design. Despite these challenges, researchers have developed innovative methodologies to test snake cognition, including maze navigation, problem-solving tasks, and response to novel stimuli. Particularly notable are studies with king cobras (Ophiophagus hannah), which have demonstrated remarkable spatial memory and prey recognition abilities. These snakes can remember the locations of prey for extended periods and distinguish between different prey types, suggesting cognitive processes beyond simple instinctual responses. Some venomous species have even shown evidence of learning from experience, modifying their hunting strategies based on previous successes or failures.

The King Cobra’s Remarkable Recognition Abilities

Among lethal reptiles, the king cobra stands out for its cognitive capabilities, particularly in the realm of recognition. Research conducted at reptile facilities in Thailand and India has documented these massive venomous snakes’ ability to recognize their regular handlers, showing different behavioral responses to familiar versus unfamiliar humans. This recognition persists even when handlers wear different clothing or approach from different angles, suggesting the snakes are responding to individual-specific cues rather than simple visual patterns. More impressive still, captive king cobras have demonstrated the ability to recognize specific individuals even after separations of several months, indicating long-term memory capabilities previously thought impossible in reptiles. Some experienced handlers report that king cobras appear to develop unique “personalities” and relationship dynamics with specific keepers, though scientists caution against anthropomorphizing these observations without further controlled studies.

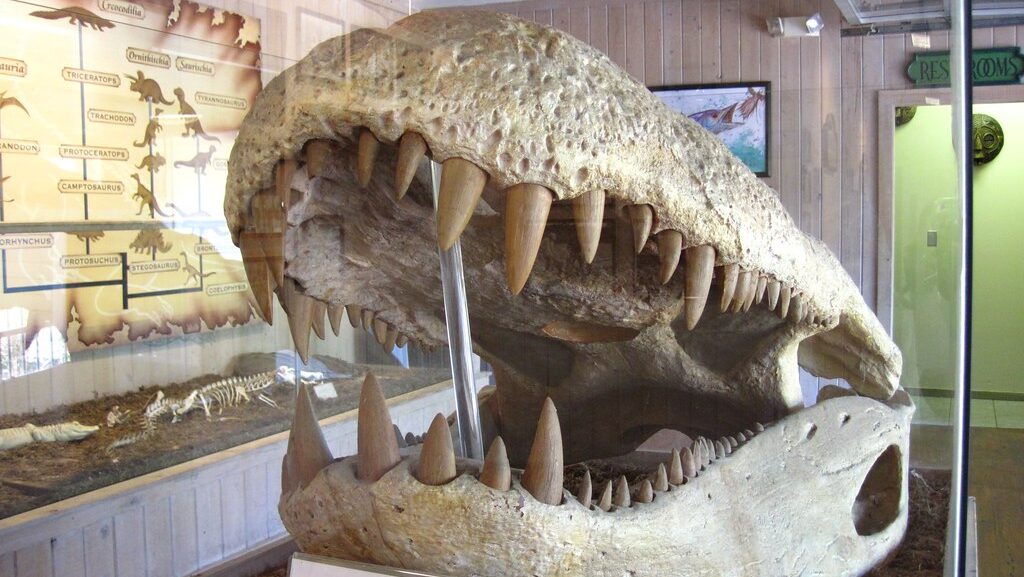

Problem-Solving Abilities in Monitor Lizards

Monitor lizards, including the potentially lethal Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), have demonstrated problem-solving abilities that rival those of some mammals. In controlled laboratory settings, Komodo dragons have solved complex food-acquisition puzzles, including manipulating latch mechanisms and navigating multi-step challenges to access rewards. What makes these achievements particularly impressive is that these reptiles often solve novel problems on their first attempt, suggesting genuine reasoning rather than simple trial-and-error learning. Research at zoos in San Diego and London has documented Komodo dragons recognizing individual keepers and modifying their behavior based on past interactions, indicating sophisticated social cognition. Perhaps most striking are observations of wild Komodo dragons employing ambush hunting techniques that require advanced spatial awareness and predictive capabilities regarding prey movement—cognitive traits once thought exclusive to mammalian predators.

Social Learning Among Crocodilians

Crocodilians—including crocodiles, alligators, and caimans—possess some of the most complex brains among reptiles and have demonstrated surprising social learning capabilities. Research led by Vladimir Dinets at the University of Tennessee documented American alligators and mugger crocodiles learning hunting techniques from observing others, suggesting a form of social transmission of knowledge. This ability to learn from conspecifics represents a sophisticated cognitive ability that was once thought absent in reptiles. Particularly interesting are observations of juvenile crocodilians watching and later mimicking the hunting strategies of adults, effectively receiving an education in predatory techniques. Some species have even been documented using tools—such as balancing sticks on their snouts to lure nesting birds—behaviors that require not only intelligence but an understanding of cause and effect relationships in their environment.

Environmental Adaptation and Intelligence

One compelling line of evidence suggesting increased intelligence in lethal reptiles comes from their demonstrated ability to adapt to changing environments. Species like the eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis), among the world’s most venomous, have shown remarkable adaptability to urban environments in Australia, modifying their hunting and hiding behaviors to exploit human infrastructure. This adaptability requires learning and behavioral flexibility rather than rigid instinctual responses. Similarly, some crocodilian species have developed sophisticated responses to human activities, including learning the patterns of tourist boats in wildlife-viewing areas and adjusting their behavior accordingly. These adaptation capabilities suggest not just basic learning but a form of environmental problem-solving that allows these species to thrive even as their habitats undergo rapid human-driven changes.

The Role of Venom in Cognitive Evolution

An intriguing hypothesis emerging from comparative studies suggests a possible link between venom evolution and cognitive development in reptiles. The production and effective deployment of venom requires sophisticated sensory processing and precise motor control, potentially creating evolutionary pressure for enhanced neural capabilities. Researchers at the University of Adelaide have proposed that the complex hunting strategies employed by many venomous snakes—involving precise strike timing, venom metering, and prey tracking—may have co-evolved with enhanced cognitive abilities. This hypothesis is supported by observations that many highly venomous species display more complex hunting behaviors and environmental adaptability than their non-venomous relatives. The need to conserve metabolically expensive venom may have driven the evolution of decision-making capabilities about when and how much venom to inject, requiring neural mechanisms for situational assessment.

Memory Capabilities in Lethal Reptiles

Recent studies have revealed surprisingly sophisticated memory capabilities in species like rattlesnakes and other vipers. Research at the University of California has documented western diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) remembering the locations of unsuccessful strikes and avoiding those areas in future hunting attempts, demonstrating both spatial memory and learned behavior modification. Even more impressive are studies showing that some venomous snakes can remember migration routes and specific hibernation dens over multiple seasons, navigating back to these locations across considerable distances. These memory capabilities extend beyond simple spatial recall to include apparent memories of specific individuals and past interactions. For example, captive black mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis) have been observed responding differently to handlers who have previously caused them stress compared to those who haven’t, even after considerable time has passed between interactions.

Evolutionary Pressures and Intelligence

The question of whether lethal reptiles are genuinely becoming smarter intersects with our understanding of evolutionary timescales and pressures. While reptiles aren’t evolving significantly enhanced cognitive abilities within human timescales, research suggests that lethal capabilities and intelligence have co-evolved over millions of years. The predatory lifestyle of many venomous species creates strong selection pressure for cognitive abilities that enhance hunting success and survival. Comparative studies between closely related venomous and non-venomous snake species suggest that those with lethal capabilities often display more complex hunting strategies and environmental problem-solving abilities. This pattern indicates that the evolutionary development of venom may have occurred alongside—or even driven—the evolution of enhanced cognitive capabilities in these lineages.

The Debate Over Reptilian Consciousness

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of reptilian intelligence research concerns the question of consciousness—whether these animals possess subjective awareness of their experiences. Traditional views held that reptiles lacked the necessary brain structures for consciousness, but this perspective has been challenged by the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness (2012), which included some reptiles among animals likely possessing consciousness. Neuroscientist Paul Cisek’s research suggests that basic consciousness may have evolved as early as the reptilian common ancestor, with evidence coming from studies of sleep states and responses to anesthesia in various reptile species. Particularly relevant to lethal reptiles are observations of apparently planned hunting behaviors in species like crocodiles and monitor lizards, which some researchers interpret as evidence of intentionality rather than mere instinct. While the debate continues, growing evidence suggests we should not dismiss the possibility of conscious experience in reptiles simply because their brains are structured differently from our own.

Technological Advances in Studying Reptile Cognition

Recent technological innovations have revolutionized our ability to study cognition in dangerous reptile species, leading to significant advances in our understanding. Non-invasive neuroimaging techniques adapted for reptiles have allowed researchers to observe brain activity during cognitive tasks without risking close contact with venomous subjects. Remote monitoring technologies, including miniaturized cameras and motion sensors, have provided unprecedented insights into natural behaviors of lethal reptiles in the wild, revealing complex decision-making processes previously hidden from scientific observation. Advanced terrarium designs with built-in cognitive testing apparatus have enabled researchers to present problem-solving challenges to venomous species while maintaining safe separation. These technological advances have not only improved safety but also reduced the stress on study subjects, resulting in more natural behaviors and more reliable data about their true cognitive capabilities.

Implications for Conservation and Management

Understanding the cognitive abilities of lethal reptiles has significant implications for their conservation and management. Recognition of these animals as intelligent beings capable of learning, memory, and perhaps even rudimentary consciousness may influence public perception and conservation policies. For species management, knowledge of problem-solving abilities and behavioral adaptability helps predict how these animals might respond to habitat changes or conservation interventions. In human-wildlife conflict situations, understanding that venomous species can learn and adapt their behaviors based on experience allows for more effective and humane management strategies. Conservation programs that account for the cognitive needs of these animals—providing appropriate environmental enrichment and social structures in captive settings, for example—are likely to be more successful in maintaining healthy populations both in captivity and in reintroduction efforts.

Future Directions in Lethal Reptile Intelligence Research

The field of reptilian cognition stands at an exciting frontier, with numerous promising directions for future research. Comparative studies examining intelligence across venomous and non-venomous species within the same genera could further illuminate the relationship between lethal capabilities and cognitive evolution. Longitudinal studies tracking cognitive development in individual animals from juvenile to adult stages would provide insights into how these abilities develop and potentially improve with experience. The application of advanced genetic and molecular techniques may identify specific genes involved in reptilian cognitive capabilities, potentially revealing evolutionary pathways to intelligence that differ from the mammalian model. As research technologies continue to advance and interest in non-mammalian cognition grows, our understanding of lethal reptile intelligence will likely undergo continued revolution, challenging long-held assumptions and revealing new dimensions of animal cognition.

The evidence suggests that lethal reptiles possess significantly greater cognitive capabilities than historically recognized by science. While they are not literally “getting smarter” in an evolutionary sense over short timescales, our understanding of their intelligence is certainly expanding rapidly. The cognitive abilities documented in venomous snakes, monitor lizards, and crocodilians—including recognition, problem-solving, social learning, and adaptive behavior—challenge traditional views of reptiles as merely instinct-driven automata. As research techniques improve and scientific interest grows, we continue to discover more sophisticated capabilities in these animals. Rather than asking if lethal reptiles are becoming more intelligent, perhaps the more accurate question is whether human science is finally becoming smart enough to recognize the complex cognition that has been there all along.

Leave a Reply