When we think of lizards shedding their skin, most of us immediately associate it with growth – the simple idea that as the reptile gets bigger, it needs to discard its too-small outer layer. While this common understanding isn’t wrong, it vastly oversimplifies one of nature’s most fascinating processes. Lizard shedding, scientifically known as ecdysis, serves multiple crucial functions beyond accommodating a growing body. From healing wounds to eliminating parasites, the shedding process represents a sophisticated biological mechanism that helps these remarkable reptiles thrive in diverse environments. This comprehensive exploration will reveal why lizard shedding is far more complex and purposeful than many realize, offering insights into the remarkable adaptability of these ancient creatures.

The Basic Mechanics of Lizard Shedding

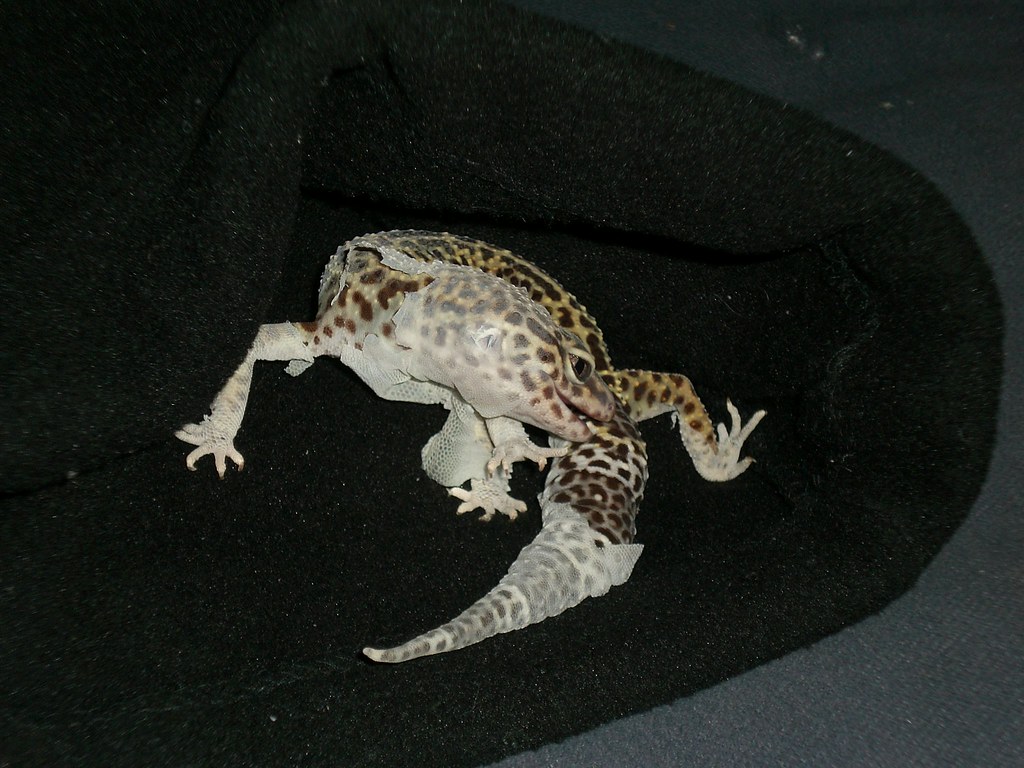

Unlike mammals who continuously shed small amounts of skin cells, lizards undergo a process called ecdysis where they remove their entire outer skin layer in one relatively synchronized event. This process begins beneath the surface when cells in the stratum germinativum (the deepest layer of the epidermis) begin to divide rapidly, creating a new skin layer underneath the old one. As this new layer forms, a special fluid fills the space between the old and new skin, gradually breaking down the connections that bind them together. Many lizards develop a characteristic milky or cloudy appearance to their eyes during pre-shedding as fluid also accumulates between the old and new eye covering. The entire process culminates when the lizard physically removes the old skin, often by rubbing against rough surfaces or using its mouth to pull away loosened sections, revealing a fresh, often more vibrantly colored exterior.

Shedding as a Healing Mechanism

One of the most remarkable aspects of lizard shedding goes beyond growth – it serves as a powerful healing mechanism. When a lizard sustains minor wounds, scratches, or abrasions to its skin, these injuries can be effectively “erased” during the next shed cycle. The damaged skin cells are simply discarded along with the rest of the old skin layer, while the newly generated skin underneath emerges pristine and unblemished. This unique capability allows lizards to recover from superficial injuries without the scarring that many other animals would experience. Some species have even evolved to shed more frequently in response to skin damage, accelerating the healing process when necessary. This regenerative aspect of shedding represents one of the reptile’s most valuable survival adaptations in environments filled with thorny vegetation, rough terrain, and territorial conflicts.

Parasite Defense Through Shedding

Lizard shedding serves as a sophisticated defense mechanism against external parasites that might otherwise plague these reptiles. Mites, ticks, and various microscopic organisms that attempt to establish themselves on a lizard’s skin are literally cast off when the host sheds its entire outer layer. This periodic “clean slate” approach provides lizards with a natural method of parasite control that few other vertebrates possess. Some research suggests that lizards may even increase their shedding frequency when parasite loads become particularly heavy, indicating a potentially adaptive response to infestation. This parasite defense system proves especially valuable for ground-dwelling species that frequently encounter environments rich in potential parasitic organisms. The relationship between parasite pressure and shedding frequency represents an ongoing area of herpetological research, with evidence suggesting that habitat and lifestyle significantly influence how lizards utilize shedding for parasite management.

Removing Accumulated Toxins

The lizard’s skin serves as more than just a physical barrier – it’s also an organ involved in waste elimination, and shedding enhances this function significantly. Through their skin, lizards can excrete certain metabolic waste products and environmental toxins that accumulate in the outer epidermal layers. When the old skin is shed, these harmful substances are effectively removed from the body, providing the lizard with a detoxification mechanism that complements its primary excretory systems. This aspect of shedding becomes particularly important for species that inhabit environments with high levels of environmental contaminants or those that consume prey containing certain toxins. Scientists have detected heavy metals and various organic compounds in shed lizard skins, demonstrating the important role this process plays in maintaining physiological balance. This detoxification benefit represents yet another dimension of shedding that transcends the simple growth narrative.

Skin Renewal for Enhanced Camouflage

For many lizard species, effective camouflage represents the difference between life and death, and shedding plays a crucial role in maintaining this protective coloration. Over time, exposure to sunlight, abrasion, and environmental factors can fade or damage the specialized pigment cells that create a lizard’s distinctive patterns and colors. Through shedding, lizards can essentially “refresh” their camouflage, ensuring that their coloration remains optimally matched to their environment. This renewal process proves especially important for species like the chameleon, whose remarkable color-changing abilities depend on properly functioning chromatophores (specialized color-containing cells). Even lizard species with more static coloration benefit from the renewal of faded patterns that might otherwise compromise their ability to blend into their surroundings. The preservation of effective camouflage through shedding represents a survival advantage completely separate from the growth function.

Shedding’s Role in Temperature Regulation

Many lizards rely partially on their skin for thermoregulation, and shedding plays a surprising role in this critical process. Newly shed skin often has different reflective and absorptive properties compared to old, worn skin, potentially improving a lizard’s ability to regulate body temperature through environmental interaction. Some desert-dwelling species have been observed basking more effectively after shedding, suggesting that fresh skin may absorb solar radiation more efficiently. Additionally, the shedding process itself can be timed to coincide with seasonal temperature changes, with some species shedding more frequently during warmer months when their metabolism and activity levels increase. Researchers have documented cases where the microscopic structure of new skin includes modifications that enhance its thermoregulatory properties based on seasonal needs. This thermoregulatory aspect of shedding illustrates how the process has evolved to serve multiple adaptive functions beyond simple growth accommodation.

Hormonal Drivers Behind Shedding Cycles

Lizard shedding is orchestrated by a complex interplay of hormones that respond to both internal and external cues, creating a sophisticated biological rhythm. Thyroid hormones play a central role in initiating and regulating the shedding process, with their production influenced by factors including nutritional status, stress levels, and environmental conditions. During breeding seasons, reproductive hormones like estrogen and testosterone can modify shedding patterns, sometimes accelerating or delaying the process to align with mating behaviors. Corticosteroid hormones, which respond to stress, can also influence when and how frequently a lizard sheds, potentially explaining why captive lizards under stress may display abnormal shedding patterns. Understanding these hormonal mechanisms has helped herpetologists recognize that shedding isn’t simply a mechanical response to growth but rather a precisely regulated physiological process that integrates multiple biological systems.

Environmental Influences on Shedding Frequency

While growth certainly affects shedding frequency, especially in young lizards, environmental factors often play an equally important role in determining how often a lizard sheds its skin. Humidity levels significantly impact the shedding process, with many species requiring specific moisture conditions to shed successfully – too dry, and the skin becomes difficult to remove; too humid, and fungal infections may develop between shed cycles. Temperature fluctuations trigger hormonal changes that can initiate or delay shedding, allowing lizards to synchronize this energy-intensive process with favorable environmental conditions. Seasonal changes in day length (photoperiod) provide another environmental cue that many lizard species use to time their shedding cycles, particularly in temperate regions where resource availability fluctuates throughout the year. These environmental influences demonstrate that lizard shedding has evolved as a responsive, adaptable process rather than a simple mechanical consequence of growth.

Shedding as an Energy Investment

The shedding process represents a significant metabolic investment for lizards, requiring substantial energy resources that go far beyond what would be needed simply to accommodate growth. The rapid cell division necessary to create a new skin layer demands increased protein synthesis and cellular energy production. During active shedding periods, many lizards display reduced activity levels and increased basking behavior, allowing them to conserve energy for the shedding process while maintaining the optimal temperature for the cellular activities involved. Some species even adjust their feeding patterns around shedding cycles, increasing food intake before shedding to build necessary energy reserves. This substantial energy investment underscores that shedding serves critical biological functions beyond growth – if growth were the only benefit, the energy economics might not justify such a resource-intensive process. The fact that lizards continue to shed throughout adulthood, long after growth has slowed or stopped, further confirms shedding’s multifaceted importance.

Shedding Patterns Across Different Lizard Species

The remarkable diversity among lizard species is reflected in their highly varied shedding patterns, which have evolved to suit different ecological niches and lifestyles. Desert-dwelling species like the bearded dragon often shed in patches rather than all at once, possibly as an adaptation to conserve moisture in arid environments. In contrast, many arboreal species like green iguanas typically shed their skin in large pieces, sometimes removing nearly the entire skin in one connected sheet. Aquatic lizards, such as the marine iguana, display shedding adaptations that account for their unique environment, with some evidence suggesting their shedding process helps remove salt buildup from their specialized salt-excreting glands. Even within the same species, individual lizards may develop personalized shedding patterns based on their specific habitat, diet, and health status. These diverse shedding strategies demonstrate how the process has been refined through evolution to serve multiple functions beyond growth accommodation.

When Shedding Goes Wrong: Dysecdysis

Problematic shedding, known as dysecdysis, reveals the complex nature of the shedding process and how it interconnects with overall health. When a lizard experiences incomplete or difficult shedding, it often signals underlying issues unrelated to growth, such as nutritional deficiencies, inadequate humidity, or systemic illness. Retained eye caps (spectacles) or skin on the toes can lead to serious complications, including infection, constricted blood flow, or even loss of digits in severe cases. Dysecdysis frequently manifests first in areas with complex topography, such as toes, tail tips, and crests, rather than in areas experiencing the most growth. For reptile keepers, understanding that problematic shedding indicates broader health concerns rather than simply a mechanical failure helps ensure appropriate veterinary care. This medical perspective on shedding underscores its importance as a health indicator that extends far beyond its role in accommodating growth.

Evolutionary Significance of Lizard Shedding

The evolution of periodic complete skin shedding represents one of the key adaptations that has allowed lizards to colonize an extraordinary range of habitats across the planet. This complex process developed from the reptilian common ancestor that split from amphibians approximately 300 million years ago, enabling early reptiles to move further from water sources while maintaining skin health. The shedding process has undergone remarkable refinement and specialization as lizards diversified into thousands of species occupying vastly different ecological niches. Evolutionary biologists view lizard shedding as an excellent example of an adaptation that began serving one primary function but evolved to address multiple biological needs through natural selection. The fact that nearly all lizard species maintain this energy-intensive process despite their tremendous diversity in size, habitat, and lifestyle testifies to shedding’s crucial importance beyond simple growth accommodation. By studying the variations in shedding among different lizard lineages, scientists gain insight into how environmental pressures shape adaptive responses over evolutionary time.

Harnessing Shedding for Scientific Research

The multifaceted nature of lizard shedding has made it a valuable tool for scientific research across multiple disciplines. Conservation biologists have developed non-invasive monitoring techniques that use collected shed skins to extract DNA, assess population genetics, and identify individual lizards without capturing or disturbing them. Toxicologists analyze shed skins to measure environmental contaminant levels in wild populations, using the shedding process’s natural toxin-sequestering function as a convenient sampling method. Medical researchers study the regenerative aspects of lizard shedding to better understand wound healing and skin renewal, with potential applications for human medicine. The hormonal regulation of shedding provides endocrinologists with insights into how environmental cues trigger physiological responses in vertebrates. This scientific utility of shedding extends far beyond what would be possible if the process served only to accommodate growth, demonstrating its biological sophistication and the wealth of information it contains.

In conclusion, lizard shedding represents a remarkably sophisticated biological process that transcends its commonly understood purpose of accommodating growth. From healing and parasite defense to toxin removal and thermoregulation, shedding serves as a multifunctional adaptation that supports lizard survival in countless ways. This complex process, fine-tuned through millions of years of evolution, reflects the incredible adaptability that has allowed lizards to thrive in diverse environments worldwide. By understanding shedding as a multifaceted biological phenomenon rather than a simple mechanical necessity, we gain deeper appreciation for the elegant solutions that nature has developed to address multiple biological challenges simultaneously. The next time you encounter a lizard’s discarded skin, remember that you’re looking at evidence of one of reptilian evolution’s most versatile and sophisticated adaptations.

Leave a Reply