When we think of domesticated animals, familiar images come to mind: the loyal dog sprawled across the living room floor, the contented cat purring on our laps, or perhaps livestock grazing peacefully in fenced pastures. But what separates these animals from their wild counterparts? The distinction between wild and domesticated goes far beyond simple human control or proximity. Domestication represents one of humanity’s most profound biological experiments—a complex, multigenerational process that has transformed certain species at genetic, behavioral, and morphological levels. This article explores the fascinating science behind what truly makes an animal domesticated, revealing how this unique human-animal partnership has evolved over thousands of years to create the companions and agricultural partners we know today.

The Definition of Domestication

Domestication represents a unique evolutionary pathway where animals adapt to human environments through genetic changes resulting from human selection. Unlike taming, which occurs within a single animal’s lifetime, true domestication involves heritable modifications that affect entire populations across generations. Scientists define domestication as a sustained multigenerational relationship in which humans assume significant control over breeding and care while providing resources that benefit the animal population. This relationship fundamentally alters the domesticated species’ behavior, appearance, and physiology compared to their wild ancestors. The process creates animals that not only tolerate human presence but often depend on it, with modifications that typically would not occur through natural selection alone. These changes represent a special form of artificial selection that has created entirely new evolutionary trajectories for species like dogs, cats, cattle, and chickens.

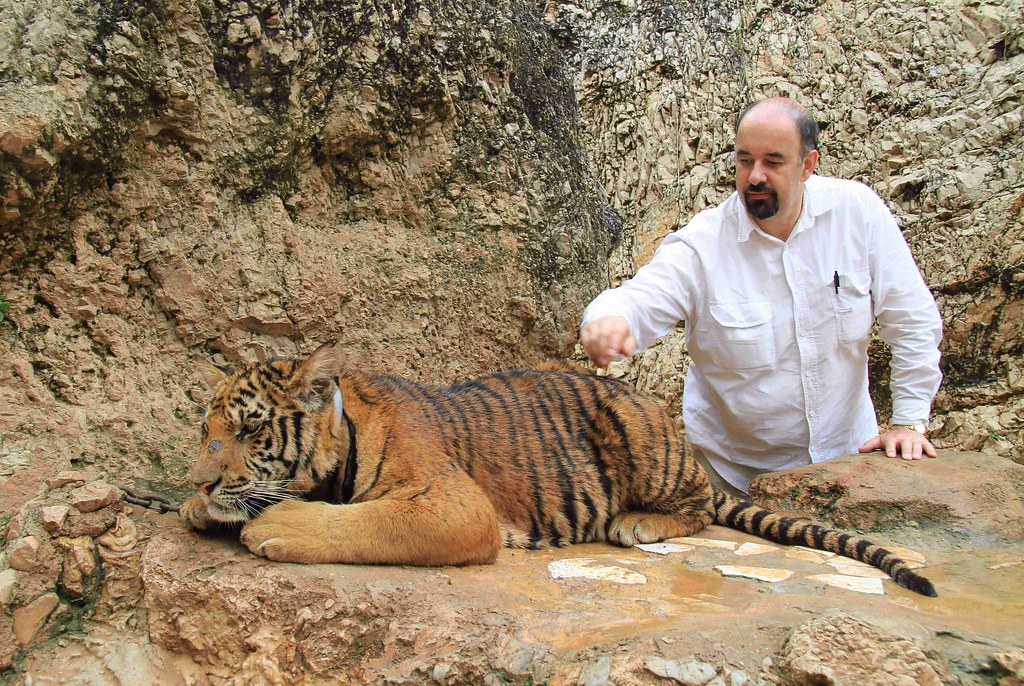

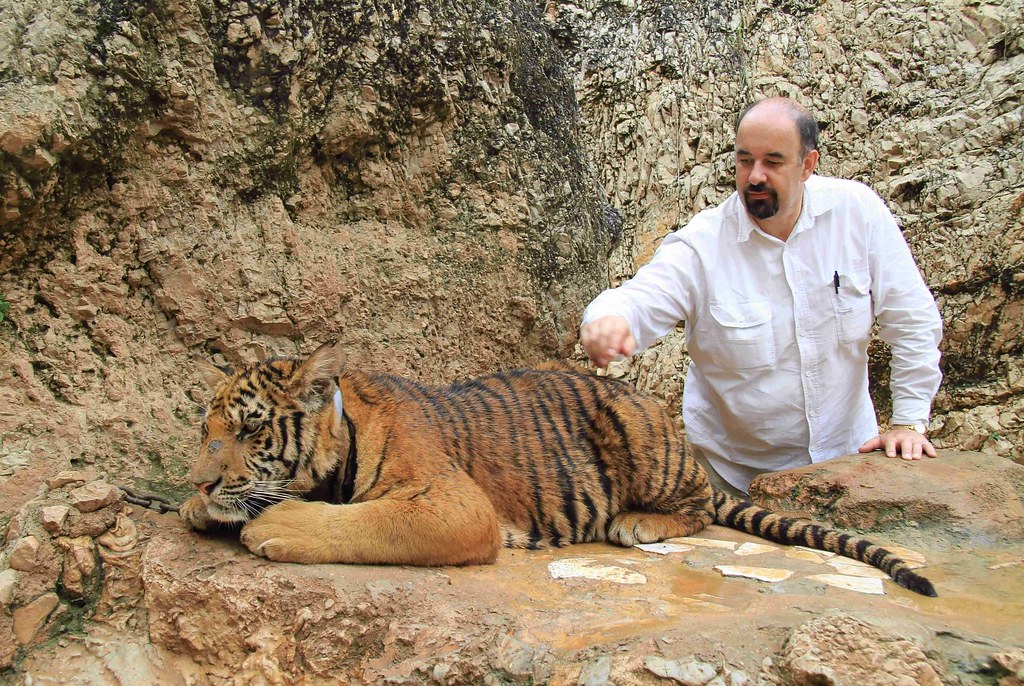

Domestication Versus Taming

One of the most common misconceptions about domestication is confusing it with taming, but these processes operate on entirely different scales. Taming refers to conditioning an individual wild animal to accept human presence and control, occurring within that animal’s lifetime through behavioral modification and positive reinforcement. A tamed tiger or elephant may learn to perform certain behaviors on command, but its offspring will still require the same training process.

Domestication, by contrast, works at the population level across many generations, fundamentally changing the genetic makeup of the entire species or subspecies. These genetic changes produce animals that innately possess traits favorable for human interaction, such as reduced fear responses and increased sociability. The distinction explains why a hand-raised wolf, despite extensive socialization, will never behave like a domestic dog, as the thousands of genetic changes that separate wolves from dogs cannot be replicated through environmental influence alone.

The Genetic Foundations of Domestication

At its core, domestication is a genetic process that modifies an animal’s DNA through selective breeding over many generations. Modern genomic studies have revealed fascinating insights into these changes, including the identification of “domestication gene regions” that appear consistently altered across multiple domesticated species. For example, genes associated with neural crest cells—which influence traits ranging from adrenal gland function to facial development—show significant modifications in domesticated animals compared to their wild counterparts. These genetic changes affect crucial systems including stress response pathways, fear thresholds, social recognition, and reproductive cycles.

Researchers have identified specific genes like WBSCR17 in dogs and SorCS1 in horses that have undergone strong selection during domestication, influencing traits from docility to coat patterns. Perhaps most remarkably, studies of foxes experimentally domesticated in Russia demonstrate that selecting for a single behavioral trait—tameness—triggers a cascade of seemingly unrelated physical changes, suggesting these characteristics are genetically linked in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The Domestication Syndrome

One of the most intriguing aspects of animal domestication is the consistent cluster of traits that appears across diverse domesticated species, known as the “domestication syndrome.” This phenomenon includes physical and behavioral characteristics that emerge repeatedly, regardless of whether the animal is a dog, cow, or rabbit. Common physical traits include floppy ears, curly tails, smaller teeth, shortened snouts, reduced brain size (particularly in areas related to alertness and stress response), patches of white fur, and retained juvenile features into adulthood.

Behaviorally, domesticated animals typically show reduced aggression, lowered stress responses, increased sociability, more frequent reproductive cycles, and altered vocalization patterns. These consistent changes appear to stem from modifications to neural crest cell development during embryonic growth. The remarkable consistency of these traits across species that were domesticated independently and for different purposes suggests deep biological connections between stress response systems, physical development, and behavioral traits that become altered together during the domestication process.

Self-Domestication in Animals

While we typically think of domestication as a human-directed process, evidence suggests some species may have undergone a form of “self-domestication” by adapting to human-adjacent habitats without direct selective breeding. The most compelling example is the early relationship between wolves and humans, where less fearful wolves may have initiated contact by scavenging around human settlements, gradually evolving into proto-dogs through natural selection favoring those that could tolerate human proximity. Similarly, research indicates house cats likely began their domestication journey by voluntarily moving into early agricultural settlements to hunt rodents attracted to grain stores, with humans only later beginning to selectively breed them.

Some researchers even propose that certain primates, particularly bonobos, have undergone self-domestication compared to their chimpanzee relatives, developing more cooperative social structures and reduced aggression. This self-domestication perspective challenges the traditional view of domestication as a purely human-controlled process, suggesting instead that some species may have effectively “chosen” to enter into relationships with humans based on mutual benefits, with genetic changes following naturally from this ecological shift.

The Historical Timeline of Domestication

Animal domestication represents one of humanity’s most transformative innovations, unfolding across distinct waves throughout prehistory and early history. The dog was likely the first domesticated animal, with genetic evidence suggesting the process began at least 15,000-30,000 years ago when humans were still hunter-gatherers. The Agricultural Revolution around 10,000-12,000 years ago marked a critical turning point, triggering the domestication of food animals like sheep, goats, and cattle, followed by work animals such as horses and donkeys. Each domestication event responded to specific human needs—sheep provided reliable meat and clothing materials, while horses revolutionized transportation, warfare, and agriculture.

The domestication timeline varies dramatically by region, with the earliest domestication events concentrated in the Fertile Crescent, China, and Mesoamerica, though independent domestication occurred on every inhabited continent. More recent domestications include the surprisingly recent selective breeding of rabbits (1800s), hamsters (1930s), and ongoing experiments with animals like silver foxes, demonstrating that domestication continues as an active process even in modern times.

Neurological Changes in Domestic Animals

The brains of domesticated animals show consistent and significant differences from their wild counterparts, reflecting profound neurological adaptations to life with humans. Most notably, domesticated species typically display reduced brain size, with particular reduction in the limbic system components responsible for fear processing, aggression, and stress response. Brain regions like the amygdala, which coordinates fear and threat assessment, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates stress hormones, show substantial modifications that reduce reactivity to potential threats.

Concurrently, domesticated animals often exhibit enhanced development in brain regions associated with social cognition and interspecies communication, allowing them to better interpret human gestures, vocalizations, and emotional states. These neurological changes manifest behaviorally through higher thresholds for triggering fear responses, increased impulse control, greater trainability, and enhanced capacity for forming social bonds outside their species. Perhaps most remarkably, domestic dogs have evolved specialized neurological adaptations for processing human faces and voices, with brain imaging studies showing they respond to human emotional expressions in ways similar to how humans process these signals from other humans.

Behavioral Hallmarks of Domestication

Behavioral changes represent perhaps the most fundamental aspect of domestication, creating animals that can thrive in human environments. The most critical behavioral shift involves reduced reactive aggression and fear responses—domesticated animals typically show dramatically higher thresholds before exhibiting defensive or panic behaviors. This reduced reactivity is coupled with increased sociability, including willingness to form social bonds with humans and other species, along with greater tolerance for crowded conditions and social proximity. Neoteny—the retention of juvenile behaviors into adulthood—appears consistently across domesticated species, manifesting as sustained playfulness, curiosity, and trainability beyond the developmental windows seen in wild counterparts.

Domestic animals also show modified communication patterns, developing more frequent vocalizations, specialized signals for human interaction, and enhanced responsiveness to human communicative cues. Perhaps most fascinatingly, truly domesticated species develop the ability to read and respond to human emotional states and intentions, with domestic dogs in particular demonstrating an almost uncanny ability to follow human pointing gestures, maintain eye contact, and recognize individual human faces—social-cognitive abilities that even our closest primate relatives generally lack.

Reproductive Modifications in Domesticated Species

One of the most profound yet often overlooked aspects of domestication involves substantial changes to reproductive biology that distinguish domestic animals from their wild ancestors. Most domesticated species show significantly altered reproductive cycles, typically producing more frequent breeding opportunities throughout the year rather than the strict seasonal breeding patterns of their wild counterparts. This shift appears in species from dogs (which can cycle multiple times annually unlike wolves) to chickens (which lay eggs nearly daily unlike the seasonal clutches of wild fowl).

Additionally, domesticated animals generally reach sexual maturity earlier, produce larger litter or clutch sizes, and demonstrate reduced mate selectivity compared to wild relatives. These reproductive changes extend to maternal behaviors, with many domesticated species showing modified nursing patterns, altered nest-building instincts, and increased tolerance for human handling of offspring.

Perhaps most significantly, domestic animals typically show reduced hormonal surges during breeding seasons, contributing to their more manageable temperaments year-round. These reproductive modifications were likely both unintentional side effects of selecting for tameness and deliberately enhanced traits that increased productivity for human purposes, creating animals biologically programmed to reproduce more efficiently under human management.

Physical Transformations Through Domestication

The physical changes wrought by domestication are often so dramatic that domesticated animals sometimes barely resemble their wild ancestors. Beyond the well-known “domestication syndrome” traits like floppy ears and curly tails, selective breeding has produced extraordinary morphological diversity within domesticated species. Consider the dramatic size range in dogs—from 2-pound Chihuahuas to 200-pound mastiffs—or the specialized body types of cattle bred variously for meat or milk production. Coat variations represent another striking change, with domesticated animals displaying colors and patterns rarely seen in wild populations, including piebald spotting, complete albinism, and novel textures from hairlessness to excessive wrinkles.

Facial structure often undergoes significant modification, with shortened muzzles, reduced teeth size, and more paedomorphic (juvenile-like) features becoming common. These physical changes aren’t merely cosmetic—they frequently correlate with functional differences in metabolism, disease resistance, and environmental adaptations. The extreme physical diversity seen in domesticated animals highlights how human selection can produce morphological changes at rates far exceeding natural evolutionary processes, creating animals specialized for particular environments and purposes that would likely never emerge under natural selection alone.

Failed Domestication Attempts

Not all species are suitable candidates for domestication, as evidenced by numerous failed attempts throughout history that reveal the specific biological prerequisites for successful human-animal partnerships. Large African mammals like zebras, hippos, and rhinoceroses have repeatedly resisted domestication despite their potential utility, primarily due to their aggressive temperaments, unpredictable behavior, and stress-sensitive reproduction. Carnivores generally prove challenging to domesticate, with only dogs and ferrets achieving full domestication status, while larger predators like lions and bears remain dangerous despite generations of captive breeding.

Several notable historical attempts have produced only partial results—cheetahs were kept by ancient Egyptians and modern royalty but have never bred reliably in captivity, while elephants remain essentially tamed rather than domesticated despite centuries of working relationships with humans. These unsuccessful cases have led zoologist Jared Diamond to propose six key criteria necessary for domestication: flexible diet, reasonably fast growth rate, ability to breed in captivity, amicable disposition, limited tendency to panic, and a social structure amenable to human leadership. The pattern of failed domestications underscores that true domestication requires specific biological predispositions rather than merely human desire for control.

The Mutual Benefits of Domestication

While domestication is often portrayed as human domination over other species, evolutionary biologists increasingly view it as a mutualistic relationship that has benefited both parties. From an evolutionary perspective, domesticated species represent some of Earth’s most successful organisms in terms of population size, geographic distribution, and genetic preservation. Dogs evolved from wolves numbering in the thousands to become the world’s most numerous carnivore, with over 900 million individuals spanning every continent. Chickens, originally jungle fowl with limited range, now number over 25 billion, making them the most abundant bird on the planet.

Domesticated animals receive consistent food sources, protection from predators, veterinary care, and shelter from environmental extremes—advantages that have allowed them to thrive far beyond the capacity of their wild ancestors. Meanwhile, humans gained crucial resources like reliable protein sources, labor assistance, transportation, and companionship that facilitated agricultural development and subsequent civilization. This perspective reframes domestication not as exploitation but as a remarkably successful evolutionary strategy where two species developed interdependence that dramatically enhanced both partners’ fitness, creating one of nature’s most effective examples of mutualistic co-evolution.

Modern Applications and the Future of Domestication

The science of domestication continues to evolve with profound implications for agriculture, conservation, and our understanding of evolution. Current research using genomic tools allows unprecedented insight into domestication’s genetic basis, with projects like the Russian fox experiment demonstrating how quickly selective breeding can transform wild species when guided by scientific principles. Several modern domestication efforts are underway, including attempts to domesticate various deer species for meat production, ongoing work with certain fish species for aquaculture, and specialized breeding programs for rodents as biomedical research models.

Conservation strategies increasingly incorporate domestication science, with de-extinction projects aiming to resurrect extinct species like passenger pigeons potentially requiring understanding of how domestication affects behavior. The study of domestication has practical applications in modern breeding programs, helping develop livestock with reduced environmental impact, improved disease resistance, and enhanced welfare characteristics.

Looking forward, emerging technologies like gene editing raise profound questions about accelerating or directing domestication processes, potentially allowing precise modification of traits that previously required centuries of selective breeding, while simultaneously sparking ethical debates about the proper boundaries of human intervention in animal evolution.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Dance of Co-Evolution

Domestication stands as one of the most remarkable examples of co-evolution on our planet—a process that has transformed both the species involved and human civilization itself. What makes an animal truly domesticated goes far beyond simple utility or obedience to humans; it represents a profound biological partnership encoded in genetics, manifested in behavior, and expressed through physical traits that have developed over thousands of generations.

The domesticated animal is not merely a tamed version of its wild ancestor but rather a new evolutionary creation—one whose biology has been reshaped to thrive in human environments while providing specific benefits to human societies. As we continue to unravel the genetic and neurological underpinnings of domestication, we gain deeper appreciation for this extraordinary relationship that has helped shape human history and created the animal companions that enrich our lives today. Understanding domestication not only illuminates our past but may help guide more ethical and sustainable relationships with animals in our future, honoring the remarkable biological dance that has connected our species with others for millennia.

Leave a Reply