For centuries, humans have sought companionship from the animal kingdom, traditionally turning to domesticated species like dogs and cats. However, a growing trend has emerged where exotic and wild animals are being kept as pets in homes across the world. From pythons to primates, tigers to toucans, the exotic pet trade has expanded dramatically, raising profound ethical questions about our relationship with wildlife. This complex issue forces us to examine where exactly we should draw the line between appropriate animal companionship and exploitation of wild species. The discussion encompasses animal welfare, conservation, public safety, and our fundamental responsibility toward the natural world.

The Growing Exotic Pet Trade

The exotic pet industry has exploded into a multi-billion-dollar global trade, with millions of wild animals changing hands annually. According to the Humane Society, approximately 15,000 primates, 5.3 million reptiles, and hundreds of thousands of birds are kept as pets in the United States alone. This market has been facilitated by online sales platforms where consumers can purchase rare species with just a few clicks, often with minimal regulatory oversight. The accessibility of these animals has normalized the ownership of species that would have been considered extraordinary companions just decades ago. From prairie dogs to fennec foxes, the definition of “pet” continues to expand, blurring the boundaries between domestic companions and wild creatures.

Understanding Animal Domestication

To properly address the ethics of exotic pet ownership, we must first understand what domestication truly means. Domestication is not simply taming an individual animal, but rather a process spanning thousands of generations where animals evolve alongside humans, developing genetic predispositions suited to human environments. Dogs, for instance, have co-evolved with humans for at least 15,000 years, developing specific traits that make them ideal companions, such as reduced aggression, increased sociability, and the ability to understand human gestures and emotions. By contrast, a wild animal raised in captivity remains genetically wild, retaining instincts and behaviors shaped by evolution for survival in natural habitats rather than human homes. This fundamental difference explains why even hand-raised wild animals typically cannot adapt fully to domestic life, regardless of human effort.

Welfare Concerns for Wild Animals in Captivity

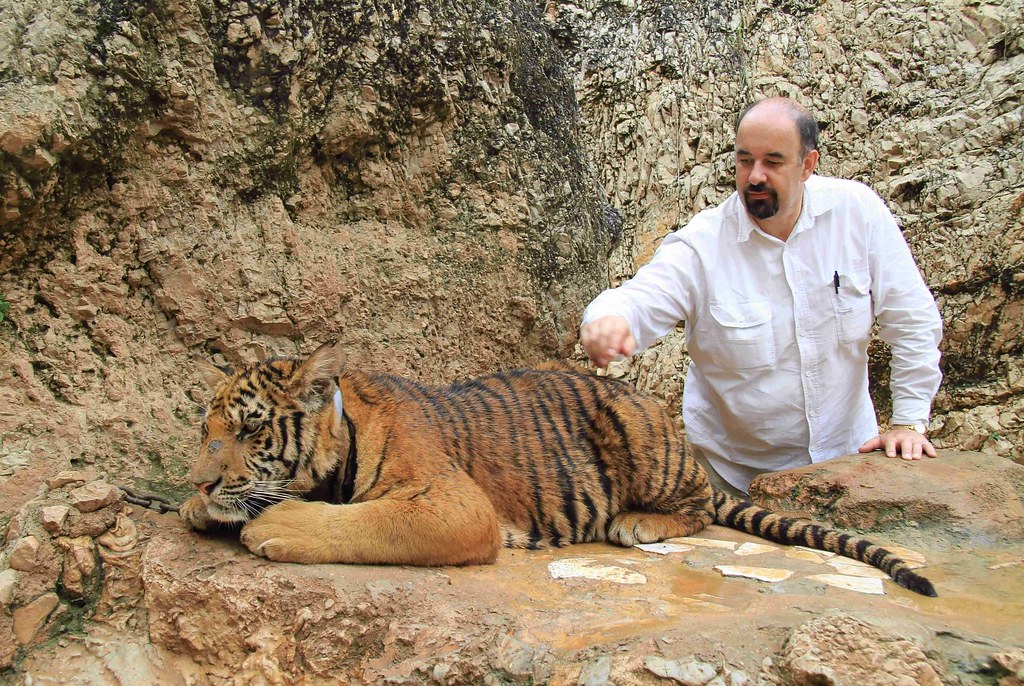

Wild animals kept as pets often suffer significant welfare issues, regardless of how well-intentioned their owners may be. Species like tigers require vast territories in the wild, sometimes up to 100 square miles, making even the most spacious domestic setting woefully inadequate. Primates have complex social structures and cognitive needs that typically cannot be met in isolation from their own kind, leading to abnormal behaviors like self-mutilation and depression. Birds like parrots, who naturally fly miles daily and live in large flocks, frequently develop feather plucking and other stress behaviors when confined to cages. Additionally, exotic pet owners rarely have access to veterinarians with specialized knowledge of wild species, meaning health problems often go undiagnosed or improperly treated. Even the most luxurious captive setting typically fails to replicate the environmental complexity these animals have evolved to need.

The Capture and Transportation Crisis

The journey from the wild to the pet store or private home often involves tremendous suffering and mortality. For every exotic bird that survives to become a pet, conservationists estimate that up to ten may die during capture, confinement, or transport. Animals are frequently taken from their natural habitats using brutal methods—snatching infant primates often involves killing their protective mothers and other family members. The transportation process typically involves cramped, unsanitary conditions where animals may be denied adequate food, water, or ventilation for extended periods. Stress-induced deaths are common during these journeys, with surviving animals often arriving at their destinations traumatized and in poor health. Even captive-bred exotic animals don’t escape these issues entirely, as they’re frequently subjected to similar transportation conditions and premature separation from their mothers to maximize profits.

Conservation Implications of the Exotic Pet Trade

The exotic pet trade poses significant threats to wildlife conservation efforts worldwide. For endangered species like certain primates, parrots, and reptiles, the removal of individuals from wild populations can push already vulnerable species closer to extinction. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) regulates international wildlife trade, but enforcement remains challenging, and illegal trafficking continues to threaten many species. Even for non-endangered species, the removal of individuals can disrupt local ecosystems and population dynamics. Furthermore, exotic pets that escape or are released by overwhelmed owners can establish invasive populations that devastate native wildlife—the Burmese pythons now decimating Everglades ecosystems stand as a stark example of this phenomenon. The collective impact of the exotic pet trade represents a significant and often underappreciated threat to global biodiversity.

Public Health and Safety Concerns

Beyond animal welfare and conservation issues, keeping wild animals as pets creates considerable public health and safety risks. Zoonotic disease transmission represents a serious concern, with approximately 75% of emerging infectious diseases originating in animals. Exotic pets can carry pathogens like herpes B virus from macaques, salmonella from reptiles, or novel influenza strains from birds—all potentially transmissible to humans. Physically, many exotic pets pose direct dangers through bites, scratches, constriction, or venomous exposures. Even smaller exotic pets can inflict serious injuries, while larger species like big cats and primates have been responsible for numerous human fatalities and disfigurements. The unpredictable nature of wild animals means that, regardless of an owner’s experience or the animal’s apparent docility, these risks never completely disappear.

The Psychological Needs of Wild Animals

Wild animals have evolved specific psychological needs that are intricately tied to their natural environments and social structures. Wolves and other pack animals require complex social hierarchies and group interactions that simply cannot be replicated in a home environment. Similarly, migratory birds have innate psychological drives to travel thousands of miles seasonally—urges that become frustrated in captivity, regardless of cage size. Many exotic animals experience profound psychological distress when denied the opportunity to express natural behaviors like foraging, hunting, establishing territories, or selecting mates. This distress often manifests in stereotypic behaviors—repetitive, seemingly purposeless actions like pacing, rocking, or self-harm that indicate severe psychological suffering. While these behaviors might seem merely odd to casual observers, they represent the animal equivalent of severe mental health disorders.

Legal Frameworks and Regulatory Gaps

The legal landscape governing exotic pet ownership varies dramatically across jurisdictions, creating a patchwork of regulations that often fail to adequately address the issue. Some states, like California, have implemented comprehensive bans on most exotic pets, while others have few restrictions beyond federally protected endangered species. At the federal level in the United States, laws like the Endangered Species Act and the Lacey Act provide some protections, but enforcement resources are limited and loopholes abound. Many municipalities have their own ordinances, creating further regulatory complexity that can be difficult for potential owners to navigate and for authorities to enforce. This inconsistent regulatory approach allows problematic trade to continue across jurisdictional boundaries and creates confusion about which species can legally be kept as pets. The resulting system often fails to protect either animal welfare or public safety effectively.

The Ethics of “Rescue” and Sanctuary

While many exotic pet owners believe they are “rescuing” animals from worse conditions, ethical questions surround this justification. True wildlife rescue organizations and accredited sanctuaries operate under specific protocols, focusing on animals that cannot be returned to the wild due to injury, habituation, or other factors making survival impossible. These facilities prioritize providing species-appropriate care rather than treating animals as pets or entertainment. By contrast, private “rescuers” often lack specialized knowledge, adequate facilities, or long-term financial resources needed for proper care of exotic species that may live for decades. Furthermore, purchasing an exotic animal, even with good intentions, financially supports the very industry that causes harm and creates more demand for wild-caught specimens. True sanctuaries distinguish themselves by not breeding, selling, or using animals for entertainment, focusing exclusively on animal welfare.

Cultural Perspectives on Wildlife Ownership

Cultural attitudes toward wildlife ownership vary considerably across societies and have evolved throughout history. In some indigenous cultures, certain wildlife species have been kept not as pets but as integral parts of traditional practices with specific cultural significance and established protocols for their care. By contrast, modern exotic pet ownership in wealthy nations often reflects status-seeking or novelty rather than cultural tradition. The social media era has accelerated this trend, with “wildlife influencers” glamorizing exotic pet ownership while rarely showing the less photogenic realities of their care. Different religious and philosophical traditions also offer varying perspectives on humanity’s relationship with wildlife, from dominion-based views that emphasize human authority over animals to interdependence models that emphasize mutual respect between species. These cultural differences complicate the development of universally accepted ethical standards regarding which animals should be kept as companions.

Alternatives to Exotic Pet Ownership

For those drawn to exotic animals, numerous ethical alternatives exist that satisfy interest without contributing to welfare or conservation problems. Wildlife rehabilitation volunteering offers hands-on experience with wild species while actively contributing to their welfare and eventual return to natural habitats. Accredited zoos and wildlife sanctuaries frequently need volunteers and offer educational programs providing close observation of exotic species in appropriate environments. Conservation organizations working in wildlife-rich regions offer “adoption” programs where donors receive updates about specific animals while supporting habitat protection. For those specifically seeking animal companionship, domesticated species like dogs and cats come in numerous breeds with varying temperaments and care requirements, while rescue organizations specializing in more unusual domesticated species like rats, rabbits, or certain bird species can provide less conventional but ethically sourced companions. These alternatives channel the human desire for connection with other species into relationships that benefit rather than harm wildlife.

Ethical Framework for Decision-Making

Developing a coherent ethical framework for exotic pet ownership requires balancing multiple considerations, including animal welfare, conservation impact, public safety, and personal liberty. A practical approach might incorporate the precautionary principle: the burden of proof should fall on those wishing to keep an animal to demonstrate it can thrive, not merely survive, in captivity. Species-specific considerations matter significantly; animals with simple environmental needs, limited space requirements, captive breeding programs, and minimal public safety risks present fewer ethical concerns than those failing these criteria. Motivations also merit ethical examination—keeping animals primarily as status symbols or for social media attention raises different concerns than educational or conservation-oriented purposes within properly accredited facilities. Perhaps most importantly, an ethical framework must center the animal’s needs rather than human desires, recognizing that our fascination with a species doesn’t automatically entitle us to possess it.

Drawing the Line: Toward a Consensus

While perfect consensus may remain elusive, certain principles can guide where society might reasonably draw the line on exotic pet ownership. Animals that cannot have their fundamental physical, psychological, and social needs met in captivity should generally remain in the wild, regardless of an owner’s resources or intentions. Species threatened by the pet trade in their native habitats deserve protection from commercial exploitation, even when captive breeding exists. Animals posing significant public health or safety risks should be restricted to properly accredited and insured facilities with appropriate expertise and containment. However, certain exotic species that adapt well to captivity, breed successfully in domestic settings, have manageable space requirements, and pose minimal safety concerns might reasonably be kept by qualified individuals under proper regulation. The key lies in developing evidence-based, species-specific standards rather than arbitrary distinctions or blanket policies that fail to account for the vast differences between various wild species.

The ethics of keeping wild animals as pets ultimately challenge us to examine our fundamental relationship with the natural world. As we gain a deeper understanding of animal cognition, welfare needs, and the ecological impacts of our choices, the ethical boundaries continue to evolve. While legitimate disagreements exist about where precisely to draw the line, most experts agree that many commonly kept exotic species suffer unnecessarily in captivity while contributing to conservation problems. The true measure of our relationship with wildlife may not be our ability to possess and control these animals, but rather our willingness to appreciate them on their own terms—even when that means admiring them from a respectful distance. As we navigate these complex ethical questions, we would do well to ensure our fascination with wild animals manifests in ways that protect rather than diminish the remarkable diversity of life with which we share our planet.

Leave a Reply