In the fascinating world of reptiles, longevity often comes as a surprising trait to many observers. While most people associate reptiles with cold, calculating predatory behavior, few realize that some of these formidable creatures can outlive humans. The combination of lethal capabilities and extraordinary lifespans makes these reptiles particularly remarkable subjects of study.

From ancient crocodilians patrolling murky waters to venomous serpents slithering through remote wilderness, these long-lived reptiles have developed remarkable adaptations that enable both their deadly nature and their impressive longevity. This exploration into the world of long-lived, lethal reptiles reveals not just their dangerous potential but also the evolutionary marvels that allow them to persist through decades of environmental changes.

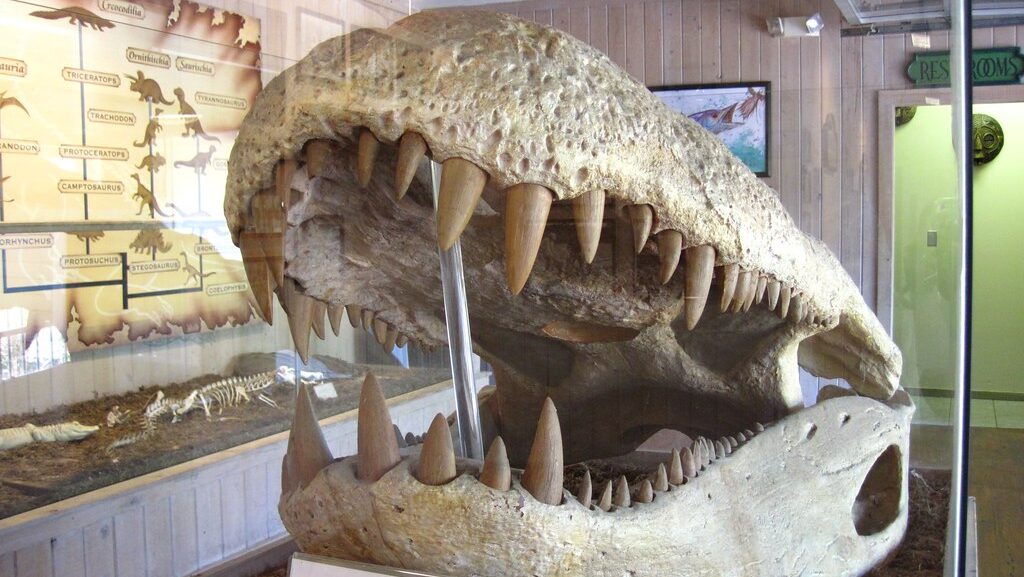

Saltwater Crocodiles: The Long-Lived Leviathans

Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) stand as the undisputed titans among lethal reptiles with exceptional longevity, commonly living 70-80 years in the wild, with some specimens potentially reaching the century mark. These massive predators, which can grow to over 20 feet long and weigh more than 2,000 pounds, possess the strongest bite force of any animal on Earth, measuring up to 3,700 pounds per square inch, more than enough to crush bones with ease.

Their patient hunting strategy, where they may wait motionless for hours before lunging at prey with explosive speed, has remained virtually unchanged for millions of years, making them living fossils of the Cretaceous period. What’s particularly remarkable about saltwater crocodiles is that they continue growing throughout their long lives, albeit at a slower rate after reaching sexual maturity, meaning the oldest specimens are often the largest and most dangerous.

Galapagos Tortoises: Gentle Giants with Remarkable Lifespans

While not lethal to humans, Galapagos tortoises (Chelonoidis nigra) deserve mention as they are among the longest-living vertebrates on Earth, with documented lifespans exceeding 170 years in some cases. These impressive reptiles can weigh up to 550 pounds and grow shells measuring over five feet in length, creating formidable armor that protects them from most natural predators. Their exceptional longevity is attributed to their slow metabolism, which allows them to go without food or water for up to a year—an adaptation that helped them survive long sea voyages that established populations on different islands.

The Galapagos tortoise’s biological makeup includes remarkable cellular repair mechanisms that effectively combat age-related diseases, making them valuable subjects for longevity research that might one day benefit human medicine. Though gentle herbivores, their massive size can make them dangerous if they accidentally pin a person against an immovable object—a rare but potential hazard when working with these ancient creatures.

Komodo Dragons: Ancient Predators with Deadly Patience

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), Earth’s largest lizard, combines longevity with lethal hunting capabilities, typically living 30-50 years with exceptional individuals reaching beyond 70 years in protected environments. These formidable predators, endemic to Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands, can grow up to 10 feet long and weigh over 300 pounds, making them the apex predators in their island ecosystems. Their hunting strategy is particularly gruesome—Komodo dragons deliver a bite containing toxic bacteria and venom-like proteins that induce shock, prevent blood clotting, and ultimately cause massive blood loss in their victims, whom they can track for miles using their keen olfactory sense.

Researchers have discovered that Komodo dragons continue growing throughout their lives, albeit at diminishing rates, meaning the oldest specimens are often the most dangerous and dominant within their territories. Their remarkable immune systems, which allow them to consume rotting carcasses without ill effects, have become the subject of scientific research seeking new antibiotics for human medicine.

Alligator Snapping Turtles: Ancient Ambush Predators

Alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminckii) represent one of North America’s most prehistoric-looking reptiles, with documented lifespans exceeding 70 years and anecdotal reports suggesting some individuals may live well over 100 years. These aquatic behemoths can weigh more than 200 pounds and possess a bite force capable of amputating human fingers or toes instantly, making them one of the most powerful biters in the reptile world.

Their most fascinating adaptation is a specialized worm-like appendage on their tongue that they wiggle to lure fish directly into their gaping mouths—a remarkable example of aggressive mimicry that allows them to be successful ambush predators despite their slow movement. Scientists have discovered that alligator snapping turtles grow continuously throughout their long lives, with their shells developing increasingly pronounced ridges and spikes with age, enhancing both their dinosaur-like appearance and defensive capabilities against potential predators.

Reticulated Pythons: Long-Lived Constrictors

Reticulated pythons (Python reticulatus), the world’s longest snakes, combine impressive longevity with formidable predatory capabilities, routinely living 20-30 years in the wild and up to 75 years in protected captivity. These massive constrictors, which can reach lengths exceeding 30 feet and weights over 300 pounds, possess enough strength to constrict and consume prey as large as deer, pigs, and in rare documented cases, even humans. Their remarkable elastic ligaments and specialized jaw structure allow them to consume prey many times the diameter of their own bodies, while their slow metabolism enables them to survive for months between substantial meals.

Despite their size and strength, reticulated pythons continue to grow incrementally throughout their lives, meaning the oldest specimens are often the most dangerous and capable of tackling the largest prey. Their extended lifespan is partially attributed to their relatively safe position at the top of their food chain and their ability to drastically reduce their metabolic rate during periods of inactivity.

Green Anacondas: Water Giants with Decades of Life

Green anacondas (Eunectes murinus), the heaviest snakes in the world, combine aquatic hunting prowess with impressive lifespans that can exceed 30 years in the wild and approach 70 years in optimal captive conditions. These massive constrictors can reach lengths of 30 feet and weights over 500 pounds, possessing enough strength to overpower caimans, capybaras, and occasionally jaguars—making them the apex predators of South American wetlands. Unlike most snakes that rely heavily on vision, anacondas have developed specialized sensory adaptations for their semi-aquatic lifestyle, including eyes and nostrils positioned on top of their heads allowing them to remain almost completely submerged while stalking prey.

Female anacondas demonstrate remarkable sexual dimorphism, growing significantly larger than males—sometimes up to five times heavier—which contributes to their exceptional longevity as the larger females face virtually no natural predators once they reach maturity. Their slow metabolism and ability to dramatically expand their bodies to accommodate enormous meals allow them to survive for months between feeding events, contributing to their extended lifespans.

American Alligators: Southern Survivors

American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) demonstrate remarkable longevity, routinely living 50 years in the wild with exceptional specimens documented reaching 70-80 years of age. These armored reptiles, which can grow to 14 feet long and weigh over 1,000 pounds, possess a bite force exceeding 2,000 pounds per square inch—enough to crush turtle shells and mammal bones with ease. Unlike many reptiles, alligators demonstrate complex social behaviors including elaborate courtship rituals, maternal care that can last up to two years, and sophisticated communication through infrasound vibrations that humans cannot hear.

Their exceptional immune systems have become the subject of scientific research, as alligators can suffer severe wounds in territorial battles yet rarely develop infections, suggesting they possess powerful natural antibiotics that might eventually benefit human medicine. Perhaps most remarkable is their biological resilience—alligators recovered from near-extinction in the mid-20th century to become one of conservation’s greatest success stories, demonstrating both individual and species-level longevity.

King Cobras: Long-Lived Rulers of the Serpent World

King cobras (Ophiophagus hannah), the world’s longest venomous snakes, combine potent neurotoxic venom with surprising longevity, commonly living 20 years in the wild and documented cases exceeding 50 years in protected environments, with some exceptional specimens potentially reaching 70 years. These impressive serpents can grow to 18 feet long and possess enough venom in a single bite to kill 20 adult humans or an elephant, making them among the most dangerous snakes on Earth. Unlike most snakes, king cobras demonstrate remarkable intelligence, including the ability to recognize individual keepers in captivity and the sophisticated behavior of building elaborate nests for their eggs—the only snakes known to construct nests and exhibit maternal care.

Their specialized diet primarily consists of other snakes, including venomous species, earning them their genus name Ophiophagus, which literally means “snake eater,” and contributing to their ecological importance as regulators of snake populations. Despite their lethal potential, king cobras typically avoid human confrontation, preferring to display their iconic hood and deliver warning hisses that can be heard from 100 feet away before resorting to defensive strikes.

Aldabra Giant Tortoises: Century-Spanning Reptiles

Aldabra giant tortoises (Aldabrachelys gigantea), while not lethal to humans, deserve inclusion for their extraordinary lifespans that routinely exceed 100 years, with some individuals documented to live beyond 150 years and unverified claims of specimens reaching over 250 years. These massive chelonians can weigh up to 550 pounds and possess shells measuring over four feet in length, creating formidable protection that has helped them survive since the time of the American Civil War or earlier. Their exceptional longevity is attributed to extremely slow metabolisms and remarkable cellular repair mechanisms that effectively combat cancer and other age-related diseases, making them valuable subjects for longevity research.

Though generally docile, these tortoises can cause serious injury through accidental crushing or pinning, particularly during territorial disputes between males when they engage in ramming contests using their massive weight. Scientists have discovered that unlike mammals, Aldabra tortoises show few signs of senescence (biological aging), maintaining reproductive capabilities, muscle mass, and organ function well into their second century of life.

Black Mambas: Long-Lived Lightning Strikes

Black mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis), Africa’s most feared snakes, combine deadly venom with surprising longevity, typically living 11-20 years in the wild and up to 50 years in protected environments, with exceptional specimens potentially reaching the 70-year mark. These slender but powerful serpents can grow to 14 feet long and move at speeds up to 12.5 miles per hour—the fastest snake in the world—allowing them to deliver multiple strikes before a victim can react. Their neurotoxic venom is so potent that without antivenom, the mortality rate approaches 100% within 7-15 hours, earning them the grim nickname “the kiss of death” throughout parts of Africa.

Unlike many venomous snakes that rely on camouflage, black mambas actively patrol large territories and will confront perceived threats, opening their inky-black mouths in warning before striking—a behavior that contributes to their fearsome reputation. Their exceptional speed, intelligence, and adaptability allow them to survive in diverse habitats across sub-Saharan Africa, contributing to their impressive lifespans despite numerous natural predators.

Gila Monsters: Venomous Desert Survivors

Gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum), one of only two venomous lizard species in the world, combine potent venom with remarkable longevity, commonly living 20-30 years in the wild and up to 50 years in protected environments, with exceptional specimens potentially reaching 70 years. These striking reptiles, adorned with distinctive orange and black beaded scales, possess venom glands in their lower jaws that deliver neurotoxic venom through capillary action rather than the pressure injection system found in venomous snakes. Their unusual metabolism allows them to store fat in their tails and liver, enabling them to survive on just 3-4 large meals per year—an adaptation perfectly suited to the harsh desert environments of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. Unlike quick-striking venomous snakes,

Gila monsters deliver a grinding bite where they latch onto victims and chew to work venom into the wound, creating an excruciating experience that, while rarely fatal to humans, causes intense pain, swelling, and lowered blood pressure. Fascinatingly, compounds in Gila monster venom have been synthesized into the diabetes drug Byetta (exenatide), demonstrating how these ancient, long-lived reptiles continue to benefit humanity despite their fearsome reputation.

Cuban Crocodiles: Aggressive Centenarians

Cuban crocodiles (Crocodylus rhombifer), while smaller than their saltwater cousins, combine extreme aggression with impressive longevity, typically living 50-75 years with some individuals potentially reaching the century mark in protected environments. These highly territorial crocodilians, which grow to about 11 feet long, are considered the most aggressive of all crocodile species, known for their willingness to charge at threats on land, including humans, and their unique ability to “gallop” at speeds approaching 20 miles per hour. Their intelligence stands out among crocodilians, with documented examples of cooperative hunting behavior where individuals work together to herd fish and even the use of sticks as bait to lure nesting birds within striking range. Despite being one of the most dangerous crocodiles relative to their size,

Cuban crocodiles are critically endangered, with fewer than 4,000 remaining in the wild due to habitat loss and hunting, making their long-lived status particularly precious from a conservation perspective. Their exceptional problem-solving abilities and social complexity suggest cognitive capabilities far beyond what was previously attributed to reptiles, contributing to scientific reconsideration of reptilian intelligence.

The Science Behind Reptilian Longevity

The remarkable longevity of these lethal reptiles stems from several evolutionary adaptations, with their ectothermic (cold-blooded) metabolism being perhaps the most significant factor enabling their extended lifespans. Unlike mammals, which burn substantial energy maintaining constant body temperatures, reptiles can reduce their metabolic rates dramatically during periods of inactivity, effectively “slowing down” their biological clocks and accumulating less cellular damage over time. Research has revealed that many long-lived reptiles possess enhanced DNA repair mechanisms and more effective antioxidant systems than shorter-lived species, allowing them to mitigate the cumulative cellular damage that typically drives aging. Their slow growth rates, which continue throughout life rather than ceasing at maturity as in mammals, contribute to their extended developmental timeline and longer overall lifespans.

Scientists studying negligible senescence—the lack of age-related deterioration seen in some reptiles—have discovered that certain species show no decline in reproductive capacity, muscle strength, or organ function well into advanced age, suggesting potential applications for human longevity research and challenging our fundamental understanding of the aging process.

Conclusion

The intersection of lethal capabilities and exceptional longevity in reptiles represents one of nature’s most fascinating evolutionary achievements. These creatures, some virtually unchanged for millions of years, demonstrate the remarkable effectiveness of their adaptations. From the massive saltwater crocodile that can outlive its human observers to venomous serpents that maintain their deadly precision through decades, these animals command both respect and scientific curiosity. Their extraordinary lifespans provide unique research opportunities in understanding aging mechanisms and potentially developing new medical interventions for humans.

As we continue to study these ancient predators, we gain not only greater appreciation for their remarkable biology but also critical insights into conserving these impressive species for future generations to witness. Their longevity stands as testament to evolutionary success—deadly efficient predators that have mastered the art of not just survival, but of thriving across the decades.

Leave a Reply