The Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) has earned a formidable reputation among reptile enthusiasts and casual observers alike. With their vibrant bluish-gray bodies adorned with orange or red spots, these large, vocal lizards are as visually striking as they are behaviorally complex. Native to Southeast Asia and parts of the Pacific Islands, Tokays have become both popular exotic pets and the subject of numerous misconceptions—particularly regarding their bite.

These nocturnal creatures, known for their distinctive “to-kay” vocalization that gives them their name, possess a bite force disproportionate to their size. In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll separate fact from fiction about Tokay geckos and their infamous bite, delving into their biology, behavior, and the realities of keeping these remarkable reptiles as pets.

The Natural History of Tokay Geckos

Tokay geckos have evolved as skilled predators in the tropical and subtropical forests of Southeast Asia, including countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and parts of India. These robust geckos typically grow to impressive lengths of 10-15 inches (25-38 cm), making them among the largest gecko species in the world.

As predominantly arboreal creatures, they have developed specialized toe pads with microscopic setae that create van der Waals forces, allowing them to climb virtually any surface—even glass and smooth ceilings. Their evolutionary history has shaped them into opportunistic hunters that primarily feed on insects, but they’re known to consume smaller lizards, young birds, and even small mammals when the opportunity arises.

Their natural habitat preferences include trees, rock crevices, and increasingly, human structures, where they often live in close proximity to people without frequent conflict.

Physical Characteristics and Identification

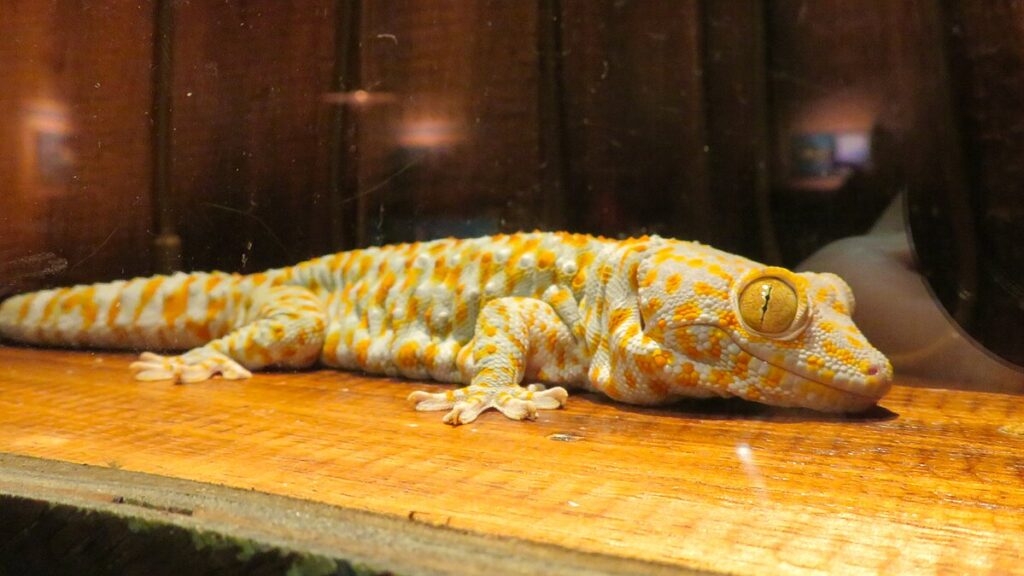

Tokay geckos possess several distinctive physical features that make them easily identifiable among gecko species. Their robust bodies are typically adorned with bluish or grayish skin covered with bright orange or red spots, creating a striking appearance that’s difficult to confuse with other geckos.

Males tend to be larger and more vibrantly colored than females, with more pronounced pre-anal pores and a bulging base of the tail where the hemipenes are located. One of their most notable features is their large, somewhat intimidating eyes with vertical pupils that can dilate widely in low light, giving them excellent night vision for hunting.

Their toes are equipped with specialized lamellae—microscopic hair-like structures that enable their famous climbing abilities through molecular attraction rather than any sticky substance. Unlike many lizards, Tokays have a relatively rigid tail that doesn’t readily detach when grabbed, an evolutionary adaptation that reflects their more aggressive defensive strategy rather than relying on tail autotomy.

The Tokay’s Vocal Communication

Unlike many reptiles, Tokay geckos are remarkably vocal, with a distinctive call that has become their namesake. Their loud, barking “TO-KAY! TO-KAY!” vocalization can be heard over considerable distances, particularly during breeding season or territorial disputes.

These vocalizations serve multiple purposes in their social structure, including mate attraction, territory establishment, and warning potential predators or rivals. Males are significantly more vocal than females, using their calls to advertise their presence to potential mates and warn competing males to stay away from their established territory. Beyond their famous namesake call,

Tokays produce a range of other vocalizations including hisses, chirps, and low growls when threatened or agitated, giving them one of the most complex vocal repertoires among reptiles. This vocal nature can be surprising to first-time keepers, who often don’t expect such loud and consistent vocalization from a reptile, especially during evening and night hours when Tokays are most active.

The Anatomy of a Tokay’s Bite

The Tokay gecko’s bite is legendarily powerful relative to its size, a fact supported by both anecdotal evidence and scientific research. Their jaw structure features a robust skull with strong adductor muscles that generate significant bite force for a lizard of their size, with some studies suggesting they can exert pressure up to 200 times their body weight. Unlike venomous reptiles, Tokays don’t possess specialized venom-delivery fangs; instead, they have numerous small, sharp teeth designed to grip and hold prey securely.

These teeth are arranged in rows along both the upper and lower jaws, creating an effective gripping surface that’s difficult to dislodge once they’ve latched on. Their biting strategy typically involves a quick lunge followed by a powerful clamp-down, with a natural instinct to hold on tenaciously rather than release quickly. This bite mechanism evolved primarily for subduing insect prey and defending against predators, but it serves equally well as a defensive mechanism against perceived human threats.

Bite Force: Myth vs. Reality

The Tokay gecko’s bite has achieved almost mythical status among reptile enthusiasts, often described in exaggerated terms that don’t necessarily reflect scientific reality. While their bite is indeed impressive for their size—particularly their reluctance to let go once they’ve bitten—scientific measurements place their bite force at approximately 30-50 Newtons, which is strong for a lizard but far from the bone-crushing capacity sometimes claimed in popular accounts.

To put this in perspective, this bite force is significantly stronger than other geckos and many lizards of similar size, but considerably less powerful than even small mammalian predators like weasels or minks.

What makes the Tokay’s bite particularly memorable is not just its strength but its persistence; when threatened, a Tokay may maintain its bite for several minutes, requiring careful removal techniques rather than simply pulling (which can cause injury to both the gecko and the person). The psychological impact of a sudden, painful bite that won’t release often leads to exaggerated recollections of the actual physical damage sustained.

Defensive Behavior and Warning Signs

Tokay geckos employ a well-defined sequence of defensive behaviors before resorting to biting, giving attentive handlers clear warning signs of their discomfort. The initial response to perceived threats typically involves inflation of the body, raising up on all four legs to appear larger, and opening the mouth wide in a threatening display.

This posturing is often accompanied by a distinctive warning vocalization—a deep, throaty growl that sounds remarkably intimidating for a lizard. If these warnings are ignored, the Tokay may progress to more active defense, including quick lateral movements of the head and body, potentially accompanied by a hissing sound.

The final warning before a bite is usually a short lunge or false strike, where the gecko moves quickly toward the perceived threat but stops short of actual contact. Understanding and respecting these warning signs is crucial for anyone handling Tokays, as they rarely bite without first displaying some combination of these defensive behaviors.

With experience, keepers can learn to recognize even subtle signs of stress in their gecko’s body language, allowing them to avoid situations where biting becomes the animal’s last resort.

What Happens When a Tokay Bites?

When a Tokay gecko does deliver a bite, the experience is both painful and potentially challenging to resolve. The initial bite typically causes sharp, localized pain due to the penetration of their small, sharp teeth into the skin, often accompanied by minor bleeding from multiple puncture wounds arranged in the pattern of the gecko’s dental arcade.

Once attached, the Tokay’s natural instinct is to maintain its grip tenaciously, sometimes for several minutes or even longer if the animal feels continually threatened. The physical damage is usually limited to surface punctures rather than deep tissue damage, though the multiple tooth marks can create an impression of more significant injury than actually occurred.

Secondary infection is a potential concern, as with any animal bite, since the mouth of a Tokay gecko contains various bacteria that can be introduced into the puncture wounds. A typical bite experience progresses from immediate sharp pain, to discomfort during the period of attachment, followed by localized soreness and minor swelling that generally resolves within a few days without serious medical intervention.

Safely Removing a Biting Tokay

Removing a firmly attached Tokay gecko requires patience and proper technique to avoid injury to both the person and the animal. The most effective approach begins with remaining calm, as panicked reactions typically cause the gecko to bite down harder and may result in injury to its delicate jaw or teeth if forceful removal is attempted.

One recommended method involves gently submerging the attached gecko in lukewarm water, which often causes them to release their grip voluntarily as they attempt to avoid potential drowning. Alternatively, applying a small amount of vinegar or alcohol to the gecko’s nose (never the eyes or mouth) may trigger a release response, though this should be done with extreme caution to avoid causing distress.

Never attempt to pull, wrench, or forcibly remove an attached Tokay, as this can tear the person’s skin and potentially break the gecko’s jaw or teeth. If these gentle methods fail, seeking assistance from an experienced reptile handler or veterinarian is recommended, particularly for inexperienced keepers who may be dealing with their first Tokay bite incident.

Medical Implications of Tokay Bites

While painful and potentially intimidating, Tokay gecko bites rarely cause serious medical complications in healthy individuals. The primary concern is the risk of localized bacterial infection, as their mouths contain various microorganisms that can be introduced into the puncture wounds.

Standard wound care, including thorough cleaning with soap and water, application of an antiseptic solution, and covering with a clean bandage, is typically sufficient for preventing infection in most cases. Some individuals may experience more pronounced localized swelling or redness due to inflammatory responses, particularly if this is their first exposure to proteins in the gecko’s saliva.

Unlike some reptiles, Tokays do not produce venom, so systemic toxicity is not a concern, despite occasional mischaracterizations of their bite as “venomous” in popular media. Medical attention should be sought if signs of infection develop (increasing pain, swelling, redness, warmth, or pus formation), if the bite victim has a compromised immune system, or if the bite occurs on the face, hands, or near joints where infection can have more serious consequences.

Taming and Handling Techniques

Contrary to their reputation for aggression, many Tokay geckos can be successfully habituated to handling through patient, consistent techniques that respect their natural behaviors. The taming process typically begins with an acclimation period of several weeks where the gecko is allowed to adjust to its environment without handling attempts, during which the keeper establishes positive associations by providing food and maintaining the habitat.

Initial handling should be brief, gentle, and ideally conducted while wearing thin gloves to protect against potential defensive bites during the early stages of the relationship. A technique called “target training” can be particularly effective, where the gecko is gently touched with a soft object before each feeding, gradually associating touch with positive outcomes rather than threat.

Successful handling depends on recognizing and respecting the gecko’s body language; sessions should be terminated at the first signs of stress such as rapid breathing, darkening coloration, or defensive posturing. While not every individual Tokay will become completely docile, many can learn to tolerate gentle, brief handling sessions when approached with consistency and respect for their boundaries.

Tokays as Pets: Realistic Expectations

Prospective Tokay gecko owners should approach these magnificent reptiles with realistic expectations about their care requirements and behavioral tendencies. Despite their striking appearance and relatively low purchase price, Tokays are generally not recommended as first reptile pets due to their initially defensive nature and specific husbandry needs.

These geckos require spacious, vertically-oriented enclosures of at least 20 gallons for a single adult, with numerous climbing surfaces, secure hiding spots, and carefully maintained temperature and humidity gradients. Their diet consists primarily of appropriately-sized insects dusted with calcium and vitamin supplements, requiring a commitment to regular feeding with live prey.

While many captive-bred individuals can become reasonably accustomed to handling with patient work, wild-caught specimens (still common in the trade) often remain defensive throughout their lives. Potential owners should also be prepared for their vocal nature, as their loud calls can be disruptive in apartment settings or during nighttime hours.

When approached with proper research and preparation, however, Tokays can be rewarding, long-lived pets (15-20 years) for the dedicated reptile enthusiast willing to appreciate them primarily as display animals rather than handling companions.

Conservation Status and Ethical Considerations

The Tokay gecko faces increasing conservation challenges throughout its native range due to extensive collection for both the pet trade and traditional medicine markets. In several countries, particularly in Southeast Asia, Tokays are harvested in large numbers based on unfounded claims about their medicinal properties, including supposed treatments for HIV/AIDS, cancer, and diabetes—claims that have no scientific support but drive significant exploitation.

Their population status varies across their range, with some localized declines documented in heavily harvested areas, leading to recent regulatory changes including their 2019 listing in CITES Appendix II, which requires permits for international trade. Ethical consumers should seek out captive-bred specimens from reputable breeders rather than supporting the wild-caught trade, which often involves poor collection and shipping practices resulting in high mortality rates.

Conservation efforts are complicated by the species’ adaptability to human environments and their introduction as invasive species in areas outside their native range, including parts of the United States. Responsible ownership includes commitment to proper care for the animal’s entire lifespan and never releasing unwanted pets into the wild, where they can become invasive and disrupt local ecosystems.

Scientific Research and Tokay Geckos

Tokay geckos have contributed significantly to scientific research across multiple disciplines, offering insights that extend well beyond herpetology. Their remarkable adhesive abilities have inspired biomimetic research in materials science, with engineers studying their setae-covered toe pads to develop new adhesive technologies that function without liquids or pressure.

Tokay vocalizations have been studied by bioacousticians to understand complex communication systems in reptiles, challenging earlier assumptions about the limited vocal capabilities of non-avian reptiles. Their impressive regenerative abilities, particularly regarding tail regrowth and wound healing, have attracted attention from medical researchers interested in tissue regeneration applications.

Recent genomic studies have further illuminated their evolutionary history and adaptation mechanisms, including the genetic basis for their vivid coloration patterns and night vision capabilities. As model organisms in various research contexts, Tokay geckos continue to provide valuable scientific insights while highlighting the importance of conservation efforts to maintain their populations in the wild for future scientific discovery.

Debunking Common Myths About Tokay Geckos

The Tokay gecko is surrounded by numerous myths and misconceptions that deserve scientific scrutiny and correction. Perhaps the most persistent myth involves claims that Tokays are venomous, which is categorically false; while their bite can be painful, they possess no venom glands or delivery mechanisms.

Another common misconception is that Tokays cannot be tamed, when in fact many individuals, particularly captive-bred specimens, can become reasonably accustomed to handling with patient work and proper techniques. The supposed medicinal properties attributed to Tokay geckos in some traditional medicine systems have been thoroughly debunked by scientific investigation, with no evidence supporting claims about treating serious diseases like cancer or HIV.

Some pet owners mistakenly believe Tokays require minimal care due to their hardiness, when in reality they need specific temperature gradients, humidity levels, and dietary requirements to thrive in captivity. Understanding these animals through a scientific lens rather than through perpetuated myths not only improves their welfare in captivity but also helps address conservation challenges driven by misinformation about their value in traditional medicine markets.

The Tokay gecko represents a fascinating study in contrasts—a creature both beautiful and intimidating, capable of both aggression and adaptation to human care. Their infamous bite, while certainly painful and memorable, is neither as dangerous as folklore suggests nor as trivial as some experienced keepers might claim. It serves as a reminder that these are wild animals with specific defensive mechanisms and behaviors that deserve respect.

For those willing to invest time in understanding Tokay behavior and creating appropriate environments, these geckos can provide years of fascinating observation and interaction. As with many exotic pets, responsible ownership begins with realistic expectations and a commitment to learning about the animal’s natural history. Whether admired from a respectful distance or gradually habituated to careful handling, the Tokay gecko remains one of the most remarkable reptiles available in the pet trade—a living connection to the rich biodiversity of Southeast Asian forests, complete with a voice and personality all its own.

Leave a Reply