The silent crisis of reptile extinction remains one of conservation’s most overlooked emergencies. While pandas, tigers, and other charismatic mammals often dominate wildlife conservation headlines, reptiles face equally severe—if not greater—threats to their survival. By 2050, experts predict we may witness the disappearance of numerous reptile species that have survived for millions of years, only to be undone by human activities in mere decades. Climate change, habitat destruction, invasive species, and wildlife trafficking have created a perfect storm threatening reptilian diversity worldwide. This article highlights fifteen reptile species teetering on the brink of extinction, whose loss would not only diminish biodiversity but also disrupt ecological systems that humans depend upon. From tiny island dwellers to iconic predators, these species represent the fragility of our planet’s evolutionary heritage and the urgent need for conservation action before it’s too late.

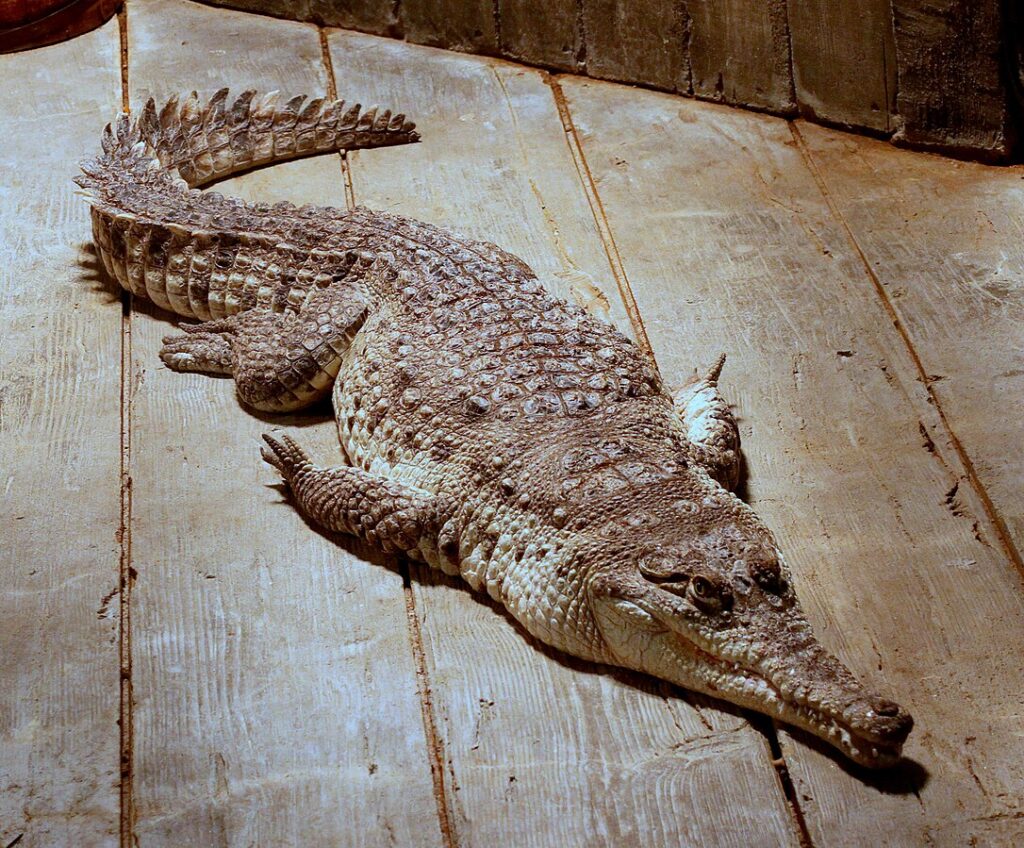

Cuban Crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer)

The Cuban crocodile, recognizable by its bright yellow coloration with dark markings and unusually long legs, faces extinction primarily due to habitat loss and hybridization with American crocodiles. Researchers estimate fewer than 3,000 individuals remain in the wild, confined to a small region within Cuba’s Zapata Swamp and the Isle of Youth. These highly intelligent reptiles demonstrate problem-solving abilities rare among crocodilians, including coordinated hunting tactics and the use of tools to lure prey. Conservation efforts have been hampered by continued wetland drainage for agriculture and illegal hunting, despite the species’ protected status under both Cuban law and international treaties. Without significant intervention to preserve their remaining habitat and prevent interbreeding with other crocodile species, the Cuban crocodile could vanish entirely by mid-century.

Ploughshare Tortoise (Astrochelys yniphora)

Native only to a tiny region of northwestern Madagascar, the ploughshare tortoise represents one of the most endangered reptiles on Earth with fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the wild. Its distinctive golden-domed shell featuring a pronounced projection under its neck (resembling a ploughshare) makes it tragically appealing to collectors in the illegal pet trade, where specimens can fetch over $100,000 on black markets. Conservation efforts have included “defacing” wild tortoises by carving identifiers into their shells to make them less desirable to poachers, yet trafficking continues to threaten their survival. The species’ extremely slow reproduction rate—females lay just one clutch of 1-6 eggs annually and take decades to reach sexual maturity—means populations cannot quickly recover from poaching pressure. Without dramatic intervention, this ancient tortoise species faces functional extinction long before 2050.

Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi)

Once numbering fewer than 25 wild individuals in 2002, the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana represents both the peril facing island reptiles and the potential for conservation success. These striking blue reptiles, which can grow to over five feet long, are endemic to Grand Cayman and have faced devastating habitat loss as the island developed for tourism and real estate. Introduced predators including cats, dogs, and rats have further decimated populations by preying on juveniles and eggs. An intensive captive breeding and reintroduction program has brought numbers up to approximately 1,000 wild iguanas, though they remain vulnerable to emerging threats like a fungal pathogen that has recently affected some populations. Climate change poses an additional challenge, as rising sea levels threaten to inundate their low-lying island habitat and increasing temperatures may skew sex ratios in this temperature-dependent species.

Pangshura Turtle (Pangshura tecta)

The Indian roofed turtle or Pangshura turtle faces multiple existential threats across its range in South Asia, with population declines exceeding 80% in recent decades. These small freshwater turtles, characterized by their distinctive roof-like keel on their carapace, suffer from rampant habitat destruction as rivers are dammed, polluted, and diverted for agriculture and development. Religious practices in some regions that involve releasing turtles into waterways have ironically contributed to their decline, as collectors harvest wild individuals to sell for these ceremonies. Additionally, the species faces significant pressure from consumption, with eggs and adults harvested for food and traditional medicine despite legal protections. Climate change threatens to exacerbate these pressures by altering river flows and increasing droughts in their native range, potentially pushing the species past the point of recovery by 2050.

Philippine Crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis)

With fewer than 200 individuals remaining in the wild, the Philippine crocodile holds the unfortunate distinction of being among the most critically endangered crocodilians on Earth. Unlike its larger, more aggressive saltwater cousin, this relatively small freshwater crocodile rarely exceeds 10 feet in length and historically posed little threat to humans, yet has been persecuted due to fear and misidentification. Habitat destruction has fragmented populations across different Philippine islands, making genetic exchange and natural recovery nearly impossible without human intervention. Conservation breeding programs have released numerous captive-bred individuals, but continued wetland conversion for agriculture and pollution from mining operations threaten these efforts. Indigenous communities have become essential partners in protecting the species, with some declaring traditional sanctuaries where hunting and habitat disturbance are prohibited, offering a glimmer of hope for this critically endangered reptile.

Burmese Starred Tortoise (Geochelone platynota)

The Burmese starred tortoise, named for the striking star-like patterns on its highly domed shell, has suffered catastrophic population collapse due to intensive collection for both food and the international pet trade. Found only in Myanmar’s central dry zone, these tortoises have lost approximately 90% of their population since the 1990s, with entire local populations completely wiped out by poaching. Their slow growth rate and low reproductive output make recovery particularly challenging, as females typically lay only 4-5 eggs per clutch and young tortoises face high mortality rates. Climate change threatens to further impact the species by altering the seasonal rainfall patterns crucial for their breeding cycle and food availability in their arid habitat. Conservation breeding centers in Myanmar have successfully produced thousands of hatchlings, but finding secure habitat for reintroduction remains difficult as human population pressure continues to transform the landscape.

Orinoco Crocodile (Crocodylus intermedius)

The Orinoco crocodile, one of the largest crocodilian species capable of reaching over 20 feet in length, has been hunted to near extinction throughout its range in the Orinoco River basin of Colombia and Venezuela. Historically slaughtered for their valuable skins, with over 3 million Orinoco crocodiles killed between the 1930s and 1960s, the species now numbers fewer than 1,500 individuals despite decades of protection. Political instability in Venezuela has hampered conservation efforts, with illegal fishing, pollution from oil extraction, and continued habitat degradation threatening remaining populations. These apex predators play a crucial role in maintaining river ecosystem health, and their decline has cascading effects throughout the food web. Reintroduction programs have released over 10,000 captive-raised individuals, but survival rates remain concerning due to continued hunting and human-wildlife conflict.

Madagascar Big-headed Turtle (Erymnochelys madagascariensis)

The Madagascar big-headed turtle, the only surviving member of its genus and a living fossil with ancestry dating back 80 million years, faces imminent extinction due to massive overharvesting for food. Local consumption has historically been sustainable, but commercial collection for food markets in urban areas has pushed the species to the brink, with over 10,000 turtles harvested annually despite legal protections. Habitat degradation compounds these threats, as rice cultivation, deforestation, and subsequent sedimentation destroy the clear, flowing waterways these turtles require. These unique reptiles, characterized by their disproportionately large heads and inability to fully retract into their shells, have tremendous scientific value as an evolutionary distinct lineage. Conservation efforts include community-based protection of nesting sites and captive breeding, but without addressing the commercial demand driving poaching, experts fear this ancient species will vanish before 2050.

Fiji Crested Iguana (Brachylophus vitiensis)

The Fiji crested iguana, with its emerald green coloration and distinctive white bands, represents one of the most threatened iguana species globally, currently restricted to just a handful of small islands. Originally described by scientists only in 1979, the species has since lost over 50% of its range, primarily due to habitat destruction as native dry forests are cleared for development and agriculture. Non-native predators introduced to the islands, including cats, rats, and mongooses, devastate juvenile populations, while introduced goats and livestock destroy critical habitat by browsing on the native plants iguanas depend upon. The species’ entire wild population on Yadua Taba Island—approximately 6,000 individuals—remains vulnerable to tropical cyclones, which climate change is making more intense and unpredictable. Recent successful captive breeding programs and habitat restoration projects offer some hope, but without addressing multiple concurrent threats, the species faces a precarious future.

Chinese Alligator (Alligator sinensis)

The Chinese alligator, one of only two alligator species in the world, has been reduced to fewer than 150 individuals in the wild, confined to a tiny region along the lower Yangtze River. Despite its fearsome appearance, this relatively small alligator rarely exceeds seven feet in length and poses little threat to humans, yet has lost 90% of its wetland habitat to agricultural development and suffered decades of persecution. Thousands exist in captivity both in China and internationally, providing a genetic reservoir for potential reintroduction, but finding suitable habitat remains problematic in one of the most densely populated and intensively farmed regions on Earth. Climate change threatens to further impact the species through altered rainfall patterns affecting the seasonal wetlands they require for breeding. Several reintroduction projects have shown promise, with evidence of wild breeding, but without large-scale habitat restoration, the species faces an uncertain future in its native range.

Mary River Turtle (Elusor macrurus)

The Mary River turtle, remarkable for its ability to breathe through specialized gills in its cloaca and the algae that often grows on its head (earning it the nickname “punk rock turtle”), faces extinction primarily due to dam construction and river modification in its highly restricted range in Queensland, Australia. Only scientifically described in 1994, the species had already suffered decades of population decline due to collection for the pet trade before receiving protection. Their extraordinarily slow maturation rate—females don’t begin reproducing until 25-30 years of age—makes population recovery exceedingly difficult even with conservation intervention. Nesting beaches have been degraded by agricultural runoff, cattle trampling, and invasive plant species, further reducing reproductive success. Climate change threatens to further stress populations through increased water temperatures, altered flow regimes, and more frequent droughts in southeastern Australia, putting this evolutionary distinct reptile at severe risk by mid-century.

Aruba Island Rattlesnake (Crotalus unicolor)

The Aruba Island rattlesnake, found nowhere else but the tiny Caribbean island of Aruba, has declined to fewer than 300 individuals due to habitat destruction, persecution, and the introduction of non-native predators. Unlike most rattlesnakes, this species has evolved to have a diminished rattle that produces little sound, an adaptation to island life without large mammalian predators. Urban development and tourism infrastructure have fragmented their habitat, restricting the snakes to a small portion of the island within Arikok National Park. Introduced cats and dogs prey directly on these snakes, while mongoose, though not currently established on Aruba, would be catastrophic if introduced. These rattlesnakes play a crucial role in controlling rodent populations on the island, making their conservation important for the broader ecosystem. A successful captive breeding program exists as insurance against extinction, but conservation efforts must focus on habitat protection and public education to change negative attitudes toward these venomous but essential predators.

Round Island Boa (Casarea dussumieri)

The Round Island boa, also known as the keel-scaled boa, represents one of the rarest snake species on Earth, having been confined to a single tiny island off Mauritius after rats and other introduced predators eliminated it from the mainland. This unique snake possesses a split jawbone structure found in no other living snake species, making it an evolutionary distinct lineage of tremendous scientific importance. Conservation efforts have included eradicating goats and rabbits from Round Island to allow native vegetation to recover, providing essential habitat for the boas which spend much of their time in trees. A captive breeding program has successfully produced offspring, though reintroduction to other predator-free islands remains challenging due to the species’ specialized habits and dietary requirements. Climate change threatens this species through rising sea levels which could eventually inundate portions of the low-lying island and through increasingly severe cyclones in the region.

San Francisco Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia)

The San Francisco garter snake, often described as one of the most beautiful serpents in North America with its striking pattern of red, turquoise, and black stripes, faces extinction due to extensive urbanization of its highly restricted range in California’s San Mateo County. Over 85% of the wetlands these snakes depend upon have been drained, filled, or altered for development since European settlement, leaving fragmented populations isolated from one another. These semi-aquatic reptiles rely heavily on California red-legged frogs and Pacific tree frogs as prey, meaning their decline follows the diminishment of amphibian populations due to pollution, habitat loss, and disease. Though legally protected under both state and federal endangered species acts since the 1970s, recovery has been slow as conservation efforts conflict with continued development pressure in the valuable real estate market surrounding San Francisco Bay. Climate change threatens to exacerbate these pressures through sea level rise affecting coastal populations and increased drought frequency impacting wetland habitat quality.

Western Swamp Tortoise (Pseudemydura umbrina)

Australia’s Western swamp tortoise holds the unfortunate distinction of being the continent’s most endangered reptile, with fewer than 50 individuals remaining in the wild by the 1980s before conservation intervention began. Native exclusively to a tiny region of seasonal swampland near Perth in Western Australia, urban expansion, agricultural development, and groundwater extraction have destroyed over 70% of their habitat. These small tortoises, rarely exceeding 15 centimeters in length, have extremely specific requirements for breeding—they need seasonal wetlands that fill during winter rains and dry during summer, a cycle increasingly disrupted by climate change. A successful captive breeding program has produced hundreds of tortoises for reintroduction, but finding suitable release sites remains challenging as Perth’s metropolitan area continues to expand. Innovative conservation approaches include creating artificial swamps with controlled hydrology and investigating potential assisted migration to areas predicted to maintain suitable climate conditions as their native range becomes too hot and dry.

The reptiles highlighted in this article represent just a fraction of the estimated 1,800 reptile species currently threatened with extinction worldwide. While some have benefited from dedicated conservation programs that have pulled them back from the brink, others continue their slide toward oblivion, often overshadowed by more charismatic endangered species. What makes reptile conservation particularly challenging is the combination of slow life histories—many species take years or decades to reach reproductive age—and the rapid pace of human-driven environmental change. Yet there is reason for hope; success stories like the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana demonstrate that with sufficient resources and commitment, even the most endangered reptiles can recover. As we approach 2050, the fate of these fifteen species and countless others will depend on our willingness to address the root causes of their decline: habitat destruction, overexploitation, invasive species, and climate change. Their survival is not merely a matter of preserving biodiversity but maintaining functional ecosystems upon which all life, including humans, ultimately depends.

Leave a Reply