When we think about endangered animals, charismatic mammals like pandas, tigers, and rhinos often dominate the conversation. However, the reptile world is facing a silent extinction crisis that receives far less media attention. These cold-blooded creatures play vital roles in their ecosystems as both predators and prey, yet many species are vanishing at alarming rates due to habitat loss, climate change, poaching, and invasive species. The following twelve reptile species are teetering on the edge of extinction, many with populations so small that they could disappear within our lifetime without urgent conservation action. From tiny island-dwelling lizards to massive prehistoric-looking crocodilians, these species represent just the tip of the iceberg in the global reptile conservation crisis.

Ploughshare Tortoise

The Ploughshare Tortoise (Astrochelys yniphora) from Madagascar is considered one of the most endangered tortoises in the world, with fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the wild. Its distinctive golden-domed shell with unique growth rings that resemble plowshare grooves makes it highly prized in the illegal pet trade, where a single tortoise can fetch tens of thousands of dollars. Conservation efforts have included establishing protected areas, captive breeding programs, and even engraving the shells of wild tortoises to make them less desirable to poachers. Despite these measures, the species continues to decline due to habitat loss from agricultural expansion and fires, alongside relentless poaching pressure that threatens to wipe out the remaining population within the next decade.

Jamaican Iguana

Once thought extinct, the Jamaican Iguana (Cyclura collei) was rediscovered in 1990 in the Hellshire Hills of Jamaica, providing a rare conservation success story that now faces renewed challenges. These large, charcoal-gray iguanas can grow up to five feet long and were decimated primarily by introduced predators like the small Indian mongoose, feral cats, and dogs that prey on both eggs and juvenile iguanas. The current wild population stands at only about 200-250 individuals confined to a small area of dry forest that is increasingly threatened by charcoal burning, bauxite mining, and urban development. Conservation efforts include headstarting programs where eggs are collected from the wild, hatched in captivity, and juveniles are released once they’re large enough to better defend themselves against predators.

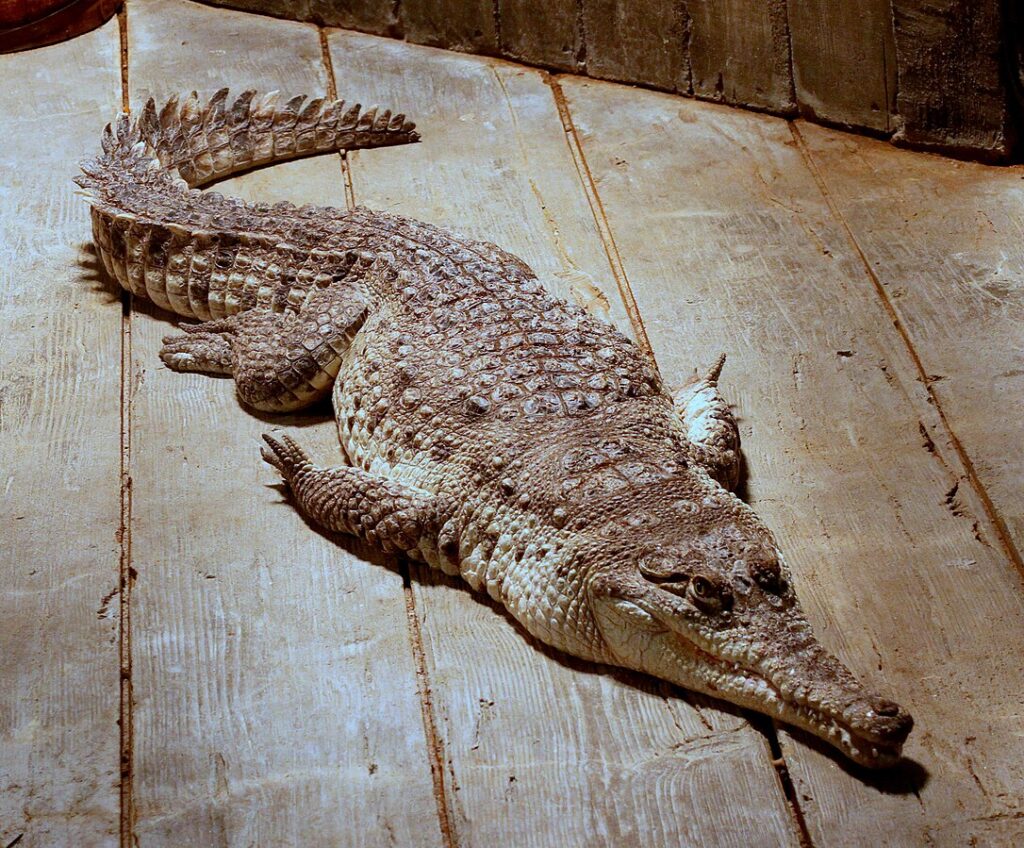

Philippine Crocodile

The Philippine Crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) is a critically endangered freshwater crocodile that now numbers fewer than 200 individuals in the wild, representing a catastrophic 85% decline over three generations. Unlike its larger and more aggressive relative, the saltwater crocodile, this smaller species (rarely exceeding 10 feet) is relatively docile and has been hunted to near extinction for its skin, meat, and out of fear. Habitat destruction through the conversion of wetlands to agricultural land has drastically reduced suitable habitat across the Philippine archipelago. Local conservation organizations have worked to change public perception of these crocodiles from fearsome predators to cultural icons worth protecting, establishing protected areas and community-based conservation programs that have shown promising results in select locations.

Cuban Crocodile

The Cuban Crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) is one of the world’s most endangered crocodilians, with only 3,000-4,000 individuals remaining in the wild in two small areas: the Zapata Swamp and the Lanier Swamp on Isla de Juventud. These relatively small crocodiles are known for their bright coloration, shortened snout, and unusually long legs that allow them to leap fully out of the water and even gallop on land when pursuing prey. Their limited range makes them particularly vulnerable to habitat degradation, hunting, and perhaps most significantly, hybridization with American crocodiles that dilutes the genetic purity of the species. Conservation strategies include captive breeding, habitat protection, and genetic management to prevent further hybridization that threatens to erode the species’ unique characteristics and ultimately lead to its extinction through genetic assimilation.

Antiguan Racer

The Antiguan Racer (Alsophis antiguae) is a harmless snake that was once abundant throughout Antigua and Barbuda but was driven to the brink of extinction following the introduction of invasive mongooses by humans in the 1890s. By 1995, only 50 individuals remained, all confined to the tiny 8.4-hectare Great Bird Island off Antigua’s coast. Through intensive conservation efforts, including mongoose eradication on select offshore islands, habitat restoration, and translocation programs, the population has gradually increased to around 1,100 individuals spread across several small islands. Despite this progress, the Antiguan Racer remains one of the rarest snakes in the world, vulnerable to extreme weather events, limited genetic diversity, and the potential reintroduction of invasive predators that could quickly reverse conservation gains.

Madagascar Big-headed Turtle

The Madagascar Big-headed Turtle (Erymnochelys madagascariensis) is a critically endangered freshwater turtle endemic to western Madagascar, with fewer than 10,000 mature individuals remaining in the wild. As its name suggests, this turtle is characterized by its disproportionately large head that cannot be retracted into its shell, making it particularly vulnerable to predators and hunters. The species faces multiple threats, including habitat loss from deforestation and wetland drainage, egg collection for consumption, hunting of adults for meat, and accidental capture in fishing nets. Climate change poses an additional threat as rising temperatures affect the sex ratios of hatchlings, potentially creating demographic imbalances that further threaten population viability. Conservation programs focus on community-based protection of nesting sites, captive breeding, and environmental education to reduce exploitation of this unique reptile.

Grand Cayman Blue Iguana

The Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi) represents one of the most successful reptile conservation stories, though it remains perilously endangered with approximately 750 individuals in the wild, up from just 15 in 2003. These striking bright blue iguanas, which can grow to over five feet long and live for decades, are endemic to Grand Cayman Island where they have been decimated by habitat destruction, road mortality, and predation by introduced dogs, cats, and rats. The Blue Iguana Recovery Program has implemented a comprehensive conservation strategy that includes captive breeding, habitat protection, and reintroduction of captive-bred iguanas to protected areas. Despite this progress, the species’ future remains precarious due to continued development pressure on the island, which has already destroyed over 90% of their natural dry shrubland habitat, leaving them dependent on actively managed protected areas for survival.

Chinese Alligator

The Chinese Alligator (Alligator sinensis), also known as the Yangtze Alligator, is a critically endangered species with fewer than 150 individuals remaining in the wild, restricted to a small area in the lower Yangtze River basin. This relatively small alligator, rarely exceeding seven feet in length, has been driven to near-extinction by habitat loss as wetlands have been converted to agricultural and industrial use, fragmentation of remaining habitat by infrastructure development, and hunting for traditional medicine. Unlike their American cousins, Chinese alligators have evolved to survive cold winters by digging burrows where they can hibernate, an adaptation that hasn’t protected them from the massive human-driven transformation of their landscape. While thousands exist in captivity both in China and abroad, reintroduction efforts face significant challenges due to the scarcity of suitable habitat and continuing development pressures in one of China’s most densely populated regions.

Orinoco Crocodile

The Orinoco Crocodile (Crocodylus intermedius) is a critically endangered species native to the Orinoco River basin in Colombia and Venezuela, with only 1,500 individuals estimated to remain in the wild. Once abundant throughout the Orinoco drainage system, these impressive reptiles—which can grow to over 20 feet in length—were hunted nearly to extinction for their valuable skins between the 1940s and 1960s before protective legislation was enacted. Despite legal protection, the species continues to face threats from illegal hunting, egg collection, habitat degradation, and conflicts with humans as fishing activities expand into their territory. Recovery efforts include captive breeding and reintroduction programs in both Colombia and Venezuela, though political instability and economic challenges in the region have complicated consistent conservation action. The crocodile’s slow reproductive rate and late sexual maturity (individuals don’t breed until they’re at least 10 years old) further hamper recovery efforts, making each breeding adult especially valuable to the species’ survival.

Fiji Crested Iguana

The Fiji Crested Iguana (Brachylophus vitiensis) is a critically endangered lizard confined to just a handful of islands in the Fiji archipelago, with the largest remaining population on Yadua Taba, a tiny 70-hectare island designated as a sanctuary for the species. These emerald green iguanas with distinctive white bands are threatened primarily by habitat destruction as the tropical dry forests they depend on are cleared for agriculture and development, along with predation by introduced mammals such as cats, rats, and mongooses. A single goat introduced to Yadua Taba in the early 2000s devastated large areas of forest before it could be removed, demonstrating the fragility of the iguana’s habitat. Recent surveys have discovered small populations on other islands, offering new hope, while captive breeding programs in international zoos provide insurance populations should the wild populations face catastrophic decline.

Burmese Starred Tortoise

The Burmese Starred Tortoise (Geochelone platynota) has suffered one of the most rapid declines of any tortoise species, with wild populations decreasing by more than 80% between 2000 and 2014 due to rampant poaching for the international pet trade and Chinese medicine markets. Named for the star-like patterns on their high-domed shells, these medium-sized tortoises are native to the central dry zone of Myanmar where fewer than 100 individuals were estimated to remain in the wild by 2013. An ambitious conservation breeding program established in Myanmar has successfully produced thousands of hatchlings, with reintroduction efforts now underway in protected areas guarded by local communities. These community-based conservation initiatives represent the species’ best hope for recovery, combining tortoise protection with sustainable livelihood opportunities for local residents who serve as tortoise guardians rather than hunters.

Madagascar Spider Tortoise

The Madagascar Spider Tortoise (Pyxis arachnoides) is a critically endangered species from the arid southwestern coastal regions of Madagascar, with population declines exceeding 80% over the past three decades. These small tortoises, named for the spider-web-like patterns on their low-domed shells, rarely exceed 6 inches in length and are highly specialized for life in sandy coastal forests and spiny thickets. Habitat destruction for charcoal production and agriculture has fragmented populations, while collection for the international pet trade and for food by local communities has further decimated numbers. The species’ extremely slow reproductive rate—females lay just one egg per year—makes recovery particularly challenging even if threats are reduced. Conservation efforts include community-based protection of remaining habitat patches, captive assurance colonies, and strengthened enforcement against wildlife trafficking, though the continuing poverty in the region drives ongoing exploitation.

The reptiles featured in this article represent just a fraction of the estimated 21% of reptile species currently threatened with extinction worldwide. Unlike mammals and birds that often receive substantial conservation attention and funding, reptiles frequently suffer from negative public perception and a lack of charismatic appeal that translates into fewer resources directed toward their preservation. Yet these ancient lineages, having survived for hundreds of millions of years including through previous mass extinction events, are now disappearing at unprecedented rates due to human activities. Each extinction represents not only the loss of a unique evolutionary history but also the disruption of ecological relationships that maintain healthy ecosystems. As we work to protect these twelve critically endangered species, we must also address the broader challenges of habitat conservation, climate change mitigation, and sustainable development that will determine the fate of countless other reptiles teetering on the edge of extinction.

Leave a Reply